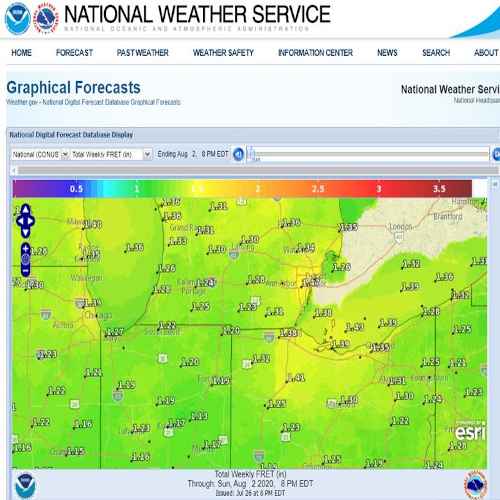

The National Weather Service is now providing daily and weekly Forecast of Reference Evapotranspiration (FRET). The interactive map tool allows an irrigator to pinpoint his section of the state and find estimated ET0 value forecast for the next week. Simply multiply the published weekly FRET value by the Kc of 1.2 to find water use for a corn crop for the week of tasseling and the three weeks to follow. You can find the information for your area at National Digital Forecast Database and use the drop down box at the top of the map and scroll down to the bottom of the list to find the Water Resources.

Michigan and Indiana producers close to the state line can have daily ET0 data sent to them by email or text by signing up for the service at Michigan State University Enviroweather website. Messages are sent at 5:30 a.m. each day providing ET0 data for the previous four days and estimates of projected ET0 for the following seven days from any of the network's 87 stations. Estimates of ET0 can also be found by going to the Enviroweather website and following the link to "More weather" and then navigate to the "Water-Use Tool heading”.

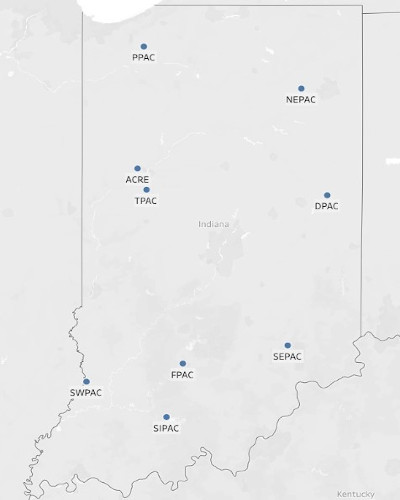

The Indiana State Climate Office provides real-time monitoring of ET0 along with other input parameters for the weather stations of the Purdue Mesonet with the Potential Evapotranspiration Monitoring Tool. Users can click on a station and view tables of values or time series graphs of the various parameters.

To make the best use of irrigation water at the time of peak water need, producers will want to try to provide five or six day’s worth of crop water use per application, typically 1 to 1.25 inches. These larger irrigation applications increase the amount of effective water available to the crop by reducing the water lost by evaporation in the corn canopy and on the residue and soil surface—about 0.1 inch per application regardless of the amount of irrigation water applied. A producer making two 0.5-inch applications provides 0.8 inch of effective water, compared to a producer making a single 1 inch application that provides 0.9 inch of effective water. Irrigators with center pivots that apply water faster than the water can infiltrate into the soil are forced to use smaller applications (less than 0.5 inch) to avoid irrigation runoff.

By the time corn reaches tassel emergence, the plant has achieved 100% of its effective rooting depth of about 3 feet. A 3-foot deep reservoir of soil moisture can hold as little as 3 inches on sand to as much as 6 inches on loam soils. Our most typical irrigated soils, sandy loams, hold between 3.5 and 4 inches in 3-feet of soil. Even with the low capacity of sandy soils, well-timed 1-1.25-inch applications rarely result in loss of water out the root zone.

For irrigators that want to avoid using the checkbook system for managing irrigation applications, soil moisture monitoring tools or digging to the depth of the wetted front 12 hours after irrigation provides an indication of irrigation need. Ideally, at least every other application should wet the soil down to 18 inches or half the rooting depth. At peak water use, corn that is inadequately watered will dry the lower rooting zone to the point that reduces nutrient uptake.

Visual signs of water stress in corn occur too late to use as a good irrigation scheduling method without lowering yields. The corn plant has a natural defense mechanism that rolls the leaves up to cut the amount of sunlight that is captured. During extremely hot days, corn may roll even if it has adequate soil moisture. A good indication of under-watering is when corn leaves are still rolled into the early evening hours or in mid-morning hours. This symptom represents severe stress and will likely reduce potential yield. Compacted areas or sandier parts of fields can be monitored for leaf rolling, providing an early warning of the field's moisture status for the rest of the crop.

Many of the irrigation systems in Indiana and Michigan do not have the pumping capacity to keep up with the peak water use of the crop. That results in the crop drawing down the soil moisture reserves. Irrigation systems that can provide 5 gallons per minute (gpm) per acre of irrigated land can provide 1 inch of water every four days or 0.25 inch per day if run continuously. Irrigation systems with less than 5 gpm per acre capacity, or when crop water use is greater than 0.25 inch per day, are reliant on the soil moisture reserves to provide soil water or yield loss can occur.

The time of day irrigation water is applied has not been critical. We have seen no major advantage or disadvantage of irrigating crops either during the night or day as far as water use efficiency. Avoiding afternoon irrigation, making multiple small applications and using pivot drop nozzles are all management practices developed for the arid west and have little to no advantage in irrigating Indiana and Michigan fields. Applying water when the crop needs it should be the producer’s most important mission.

While time of day of irrigation is normally not critical, irrigation applications made prior to the heat of the day can be beneficial to pollinating corn when afternoon temperatures are extremely high. By wetting the canopy and soil surface, temperatures are lowered and the relative humidity is raised, both of which can help the pollination process. The myth of “cold shock” to the crop scares some producers into avoiding irrigation just when it is needed the most.

Source : msu.edu