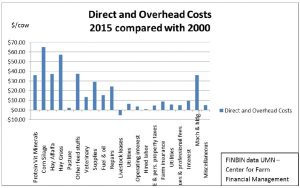

As the price of beef comes back down from record highs, we just have to be patient for input costs to decline by a similar amount. . . Yeah, right, I also have a bridge to sell. Cow/Calf enterprise data summarized by the Center for Farm Financial Management at UMN (FINBIN) shows that in 2000 the average cow /calf operator had $349 in direct and overhead costs. By 2015 this number had soared to $747/cow in direct and overhead costs. This is a 114% increase. How’s a producer supposed to maintain let alone improve their margin with rising costs and falling prices?

Can producers kick up production? The data suggests, no. Comparing 2000 and 2015, calving, weaning, culling rates are comparable, and weaning weights declined from 529 to 510 lbs. So we need to look at the expense side of the ledger.

Feed costs represent ~70% of the total annual costs for cow calf producers, and offers the greatest opportunity to control expenses. In this 2000/2015 time frame, feed costs increased 116%, that’s right more than doubled.

We know that nutritional requirements of beef cows varies with her stage of production from late gestation>early lactation>mid lactation>late lactation>early gestation>mid gestation. Energy (TDN) and protein requirements start to rise right before calving and peaks 45 days post calving. Then starts a long trail downward.

Winter calving is by far the most common calving season in Wisconsin. Spring does not begin until March 20. There are lots of reasons that beef producers calve when they do. Labor, facilities, tradition – we’ve always done it that way, desire to sell a larger calf in fall. When we calve in winter or even early spring we rely heavily on stored feeds. Not only are we feeding more protein and TDN, the cow consumes more total pounds eating for lactation, the highest nutritional demand of the year.

Cows with a dry winter coat have a thermal neutral temperature of 17F. If the coat is wet or mud/manure covered, the cow loses thermal efficiency, i.e. she eats more simply to generate body heat. If it gets much colder than 17F, her intake will increase. This additional intake is all coming from more stored feeds, re: greater cost.

Winter calving comes with increased challenges, snow storms, rain, mud, chilled calves, etc. .

Dr. Kris Ringwall, Extension Beef Specialist at NDSU Dickinson Research Center was a presenter at the Driftless Region Beef Conference in February. The center looked at their beef cow financial data, feed costs were increasing, labor costs were increasing and margins were shrinking, simply tweaking their current system wasn’t going to get them far enough. They made the decision to change the system from March calving to May calving.

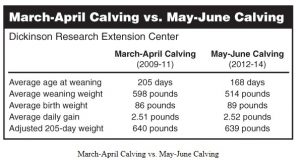

One concern of moving calving dates later is now we’re breeding in the heat of summer and it may be more difficult to get and keep cows bred. The center compared the previous three years before the switch to the subsequent three years after. In pregnancy checks, 98.96% of March cows were pregnant compared with 98.23% of the May cows.

You’re thinking- it’s North Dakota they must have cooler summers so that won’t work here. U.S. Climate data comparing Dickinson with Platteville, WI shows that Dickinson has slightly warmer summer days and cooler evenings. SW Wisconsin is more humid but even here our summer evenings cool off allowing cows to breed.

Late spring calves are smaller . . . sort of. May calves at Dickinson were lighter than March calves, BUT they were also 37 days younger and when ADG and 205 day adjusted weights were compared there was . . . no difference. One difference was the May born calves had a slightly higher weaning rate (lower death loss), so we sell more calves/cow.

If pasture is a major feed resource, by shifting breeding/calving dates later, cattlemen can better match the cows’ nutrition curve to the pasture forage growth curve. The cows’ peak demand occurs at peak forage growth and quality. Grazed forages are our single cheapest feed resource.

In the NDSU case, shifting breeding and calving, allowed them to better incorporate cover crops which can be grazed later in the season by late lactation cows rather than dry cows. Cows were able to out winter on corn stalks for a longer period without high nutritional demands of lactation, thereby reducing stored feed costs.

It’s difficult to make significant changes. Before making changes, we need to understand what per cow costs are and then evaluate our feed resources, labor and facilities availability. If we have significant pasture resource, it may be time to re-consider when we chose to calve.

Source : uwex.edu