By Meaghan Anderson and Ashley Dean et.al

One of the most common questions coming out of any winter is “how did the insects do?” In winters like this, where we have extended cold spells, farmers and agronomists alike want to know whether the cold was enough to kill some of our most common crop pests. Entomologists Erin Hodgson and Ashley Dean have written several articles in the past regarding how (and how well) insect pests overwinter. You can find those resources listed below.

The short answer is that while insects can be a bit like goldilocks – preferring to overwinter in conditions and soils that are not too wet, not too dry, not too sandy, and not too clay – they are more resilient than we’d all prefer to believe. Many factors determine overwintering success, including the cold-hardiness of the insect, the temperatures insects are exposed to, temperature fluctuations, duration of cold spells, and the amount of time between cold spells.

Species may vary in their preferences for overwintering locations. Some overwinter in residue (bean leaf beetle) or on plants (soybean aphid), while others prefer to overwinter in the soil (Japanese beetle). For those that overwinter in the soil, the depth and location of overwintering is generally influenced by soil characteristics (texture, moisture) and the proximity to preferred habitat/feeding sites (e.g., corn rootworm eggs are laid at the base of corn plants) for specific species.

How cold is too cold?

We have no doubt that the Polar Vortex system we are currently experiencing is harder on insects than more typical, moderate winter temperatures. While air temperatures are frigid, the snow cover and soil act as good insulators for insects that overwinter in the soil to reduce their exposure to long cold spells. Fresh snow is composed of air trapped among ice crystals, which helps reduce heat movement from the warm soil to the cold air.

All insects have a lower lethal temperature that causes death when surpassed. During the winter, insects attempt to avoid death due to freezing in different ways; some insects actually freeze but produce cryoprotectants to survive, while others avoid freezing by producing antifreeze to lower their supercooling point (the point at which water freezes). Corn rootworms are a particular insect pest of concern for many Iowa farmers. For example, Ellsbury and Lee (2004) noted northern corn rootworms as having a supercooled temperature as low as -27 degrees Celsius (-16.6 degrees Fahrenheit), and Godfrey et al. (1995) found that western corn rootworm eggs could survive extended periods of exposure to -10 degrees Celsius (14 degrees Fahrenheit). While some corn rootworm eggs may not survive the winter at warmer temperatures, this gives us an idea of just how tolerant they are to the cold.

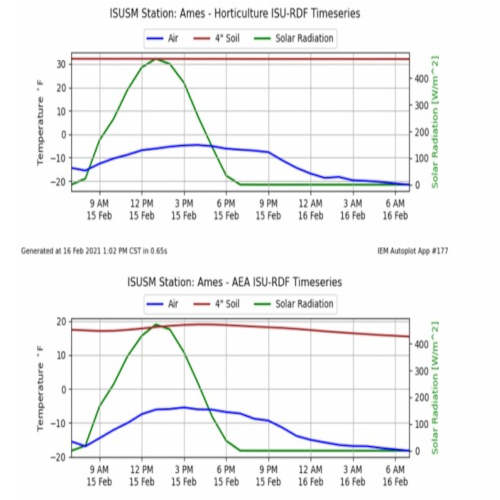

The ISU Soil Moisture Network has soil temperature probes across the state at depths of four, 12, 24, and 50 inches. The probes at the four-inch depth at the Agricultural Engineering and Agronomy (AEA) Farm and the ISU Horticultural Research Station in central Iowa have recorded temperatures varying from 15.4 to 19 degrees Fahrenheit and 33.1 to 33.2 Fahrenheit in the last 24 hours (7:00 a.m. Feb. 15 – Feb. 16), respectively (Figure 1). The difference in soil temperature recorded at these two stations only 15 miles apart is probably due to lack of snow cover at the AEA Farm location. Despite frigid air temperatures hovering below or near zero, four-inch soil temperatures (in Fahrenheit) are in the teens to low 20s at the coldest locations and in the upper 20s or low 30s at other sites (likely with more snow cover). The snow cover and soil are keeping insects at four depth more protected than those closer to the surface or exposed to the air.

Figure 1. Air (blue) and 4” soil (brown) temperature at two ISU Soil Moisture Network locations from 7:00 a.m. on February 15 to 7:00 a.m. on February 16.