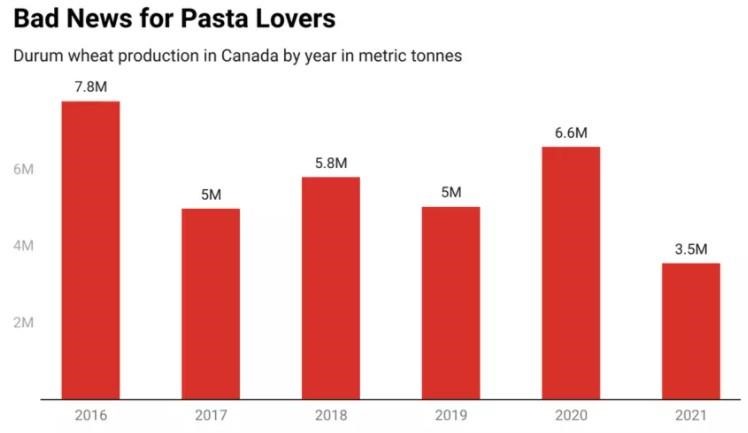

In Canada, the world’s biggest exporter of durum wheat, record temperatures this past summer and pervasive drought attributed to climate change reduced the country's anticipated production for this year to about 3.5 million metric tonnes, a nearly 50% decline from last year. European producers were meanwhile deluged by record rainfall chalked up to warming temperatures.

Durum wheat is far from the only staple being impacted by the climate crisis. Coffee is likely to become more expensive and lower-quality as a result, for example, about 70,000 farms in California, the biggest food producer in the US, are operating on drastically-reduced water rations, and the Paraná River in South America, a vital means of transporting grains, recently hit a 77-year low.

In many ways, the heavy impact of climate change on the global food supply chain has been made even heavier by COVID-19.

The results of that heavier impact have surfaced in diverse and unnerving ways – ketchup packets suddenly fell into such short supply that new production lines had to be built, flour supplies fell victim to a surge in home baking, and it suddenly got a lot harder to feed children in schools.

Last year, according to the UN, global hunger surged as the pandemic disrupted supply chains and inflated food prices. Nearly 10% of the global population was undernourished, the UN reported, and nearly a third didn’t consistently have access to the food they need on a daily basis.

Modern supply chains are generally built for efficiency. But they’re also not often designed to withstand the unpredictability wrought by a sudden disaster.

Recently, a record number of cargo ships were forced to idle at one time near southern California’s busy ports due to pandemic-related disruptions, and dry bulk carrier congestion has hit historic levels in China.

Climate change has been far from sudden, of course. Alarm bells have been ringing for many years, though experts say responses have generally been lacking.

In some ways, the pandemic may actually be helpful in this regard. For one thing, the temporary roadblocks it’s erected in the global food supply chain seem to have woken many people up to the fact that climate change can do the same sort of thing, albeit on a more permanent basis.

The issue of climate impact on agricultural yields has been a topic of discussion during the Forum’s Sustainable Development Impact Summit, which is happening this week. Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, for example, noted that the production of many crops in his country has declined following decades of upward progress.

Click here to see more...