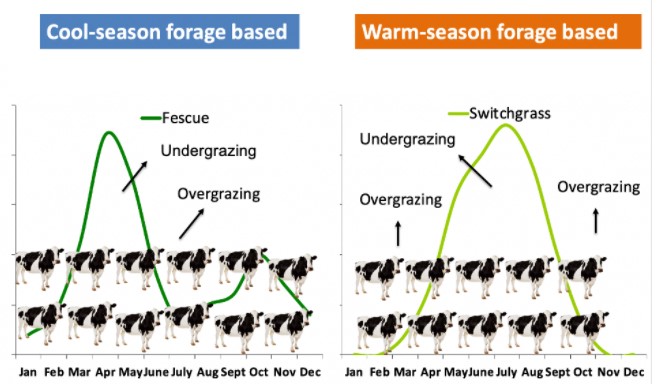

Forage productivity, however, is not constant, and it can be influenced by several factors, weather being one of the major ones. In North Carolina and the transition zone of the eastern USA, productivity and distribution of cool- and warm-season forages have a distinct pattern. For example, tall fescue is most productive in spring and fall, while switchgrass and bermudagrass are most productive during the summer. Thus, if the number of animals remains constant during the year (like it is usually the case for most farmers), then, there will be periods of under- and over-grazing if only one type of forage species is used (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Figures showing periods of under- and over-grazing for cool- and warm-season based grazing systems at the same stocking rate.

Year-round grazing management is possible, but only with a combination of forages (i.e., cool- and warm-season) and management practices (i.e., stockpiling). To define an adequate stocking rate that will work for your specific goals and environment, first, start looking for the types of forages and the average pastureland productivity in your specific area. No other grazing management practice, such as the use of electric fences, feeding minerals, soil sampling, fertilization, or weed management (although important) can overcome the failure of defining an adequate stocking rate.

Source : ncsu.edu