During germination, seedling emergence, and up to the 5-leaf stage, the growing point will be at ~1 inch depth. At this depth, it is already protected from the ambient air temperatures. Even if above-ground leaves freeze, the plant will survive and continue its development as long as the crown does not suffer any freezing injury.

Ideally, we like to emergence to be as quick as possible and yield a healthy, vigorous seedling. Daytime highs in the high sixties to low seventies and night temperatures around forty are great and will allow the crop to emerge in 8 to 10 days and make for a robust stand. Protracted emergence will predispose the seeding to attacks of soilborne fungi like Pythium damping off or common root rot, ultimately reducing stands.

However, if in the coming weeks, the current weather continues its current streak and your fields are ready to be seeded, I would seriously look at the immediate weather forecast at that time. If it looks like you can accumulate some 120 to 180 GGD between getting the seed in the ground and a return to freezing temperatures, I would not be afraid to go as the risk/reward equation is not a fool's errand.

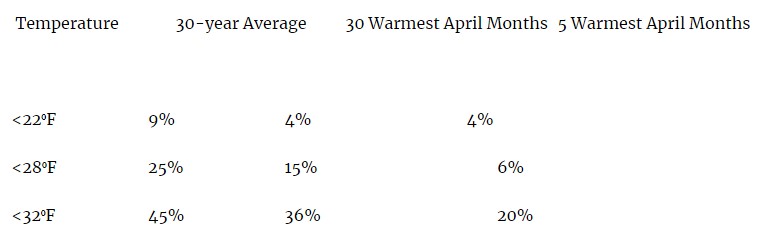

To assess the risk of winter returning you can do what I did in 2012 to quantify that risk. I took the weather records from the Northwest Research & Outreach Center that date back all the way to 1890. If I took the 30-year climate normal at that time (1981 through 2010), winter could still return in April and if it did, the number of days the minimum temperatures went below 22⁰F between April 1 and May 15 was relatively small at 9% (Table 1). The number of days the nighttime temperatures dipped below 28⁰F was much greater at 25%. If however, the warmer weather continues and I looked at the 30 warmest April months on record, these percentages were cut in half. Taking the warmest 5 April months on record, it cuts those percentages again in half.

Obviously, that was somewhat of a roughshod approach as each individual day has its own probability function, meaning that it has its own mean and distribution around that mean. To do these calculations statistically correct you would have to calculate the probability that temperatures dropped below 22, 28, and 32 degrees for each individual day and then average them out over the same period. Intuitively you would understand that the risk is greatest in late March/early April and diminishes with each day the season progresses.

The bottom line is that frost is likely to return after you seed the crop this early but the odds of really cold temperatures that could damage the crown are relatively small when looking at historical weather data with similar weather records. Of course, if any snow accompanies the cold weather, the snow will act as insulation and reduce the risk of the crowns freezing further.

Table 1. The percentage of days that temperatures dropped below 22, 28, or 32⁰F between April 1 and May 15 in the last 30 years, the warmest 30 April months on record and the 5 warmest April months on record at the NWROC.

Source : umn.edu