Firstly, the phenomena we have encountered this last month can be described as the result of a “weather market”—a period of time in which traders make decisions based on current and prospective weather conditions that affect the production (supply) of a particular commodity in hopes of capturing a premium related to production risk. Put another way, this is a “supply-side” market driver as there is a risk to the volume of production.

The weather in question is that of the central United States as the region is under varying degrees of drought. The most recent USDA Drought Monitor (6/29/2023) report indicates that 53% of the contiguous United States is experiencing some level of drought. On a per crop basis the monitor indicates that 70% of corn growing regions and 63% of soybean growing regions are in some degree of drought. Reports in June indicated progressively higher levels of moisture stress in large swaths of the corn belt. As we well know, corn demands roughly an inch of rain each week when in the rapid growth stages and entering pollination. With this, traders bet on a reduction in yield for this year’s corn crop, thus raising the price through market actions.

Traders not only looked at retrospective reports like the drought monitor, but also analyzed weather forecasts for these regions. For much of the month, neither the GFS (U.S. based) nor the ECMWF (European based) weather models predicted any significant rainfall for these regions. In some instances, the models added further uncertainty as the GFS forecasted sporadic precipitation events while the ECMWF left the radar screen blank. On the ground, drought regions experienced high winds and high temperatures further drying out soils and inducing greater rates of transpiration from an already moisture-stressed crop.

With these factors at play, market participants found reason to purchase grain futures contracts or options in hopes of realizing some future increases in commodity prices. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) reports the commitment of traders market positions in which the non-commercial speculative entities (aka “the funds”–referring to money managers like hedge funds or mutual funds) with significant market power were in a net short position by about 60-70k contracts of corn entering the month of June. As the month progressed, the most recent report indicates that these market participants held a 100-115k net long position (As of 6/27/2023). Effectively, this means that these market participants were betting on a decline in the corn futures market at the end of May, only to quickly reverse course and bet a far larger position on an increase in the corn futures market price. There is a significant delay in the release of these reports, so it is difficult to ascertain where the funds stand after the last week in June ending in a Friday sell-off in corn and wheat. Though current estimates place fund positions back to near neutral (equal quantity of long and short positions) in corn. Traders in the wheat futures market followed a similar path to corn, while traders in the soybean futures market are currently estimated to be in a significantly long position.

The weather trading continued later into the month; price action in the last week of June saw falling prices as regions of the Midwest realized modest precipitation accumulations. No less, the GFS and ECMWF weather models agreed on additional future precipitation events thus indicating a potential for salvage of the current crop.

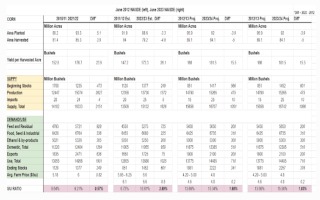

To cap off an already topsy-turvy last week in June and generally volatile month, the USDA released Quarterly Grain Stocks and Planted Acreage reports on Friday, June 30th. The grain stocks report followed analysts estimates, however the planted acreage report unexpectedly and significantly deviated from the market sentiments. Reported planted corn acreage rose roughly 2 million acres from a previous prediction report, and an increase of about 5% from last year. Soybean acreage fell by about 5% compared to last year, which is about 4.2 million acres lower than the average trade estimate. Markets traded this supply-side news as corn fell back to prices not seen since December of 2020. On the other hand, the soybean market is trading back to levels from mid-June.

The volatility of these markets is unmistakably high. Not only is the current implied volatility of these markets (based on options prices) higher than 60-80% of all trading days in the previous year, but trading strategies involving options require larger investments.

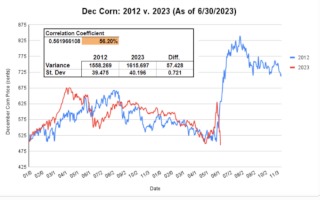

Marketing a crop in these conditions is undoubtedly challenging. We may look to previous years for guidance, though even this is uncertain. Analysts have likened the run-up in the grain markets to those in 2012 when a similar drought induced crop failures across the Midwest. Currently, there exists a 0.56 correlation coefficient between the 2012 December contract and the 2023 December contract (Figure 1). In truth, this exact discussion is nothing new; many marketing professionals and memorious farmers recall the drought of 2012 that spurred a dramatic run-up in the corn price reaching a peak of $8.49 on August 10th, 2012 and will refer to this observation whenever a drought emerges in the Midwest. Although, there is a correlation in prices between Dec’12 Corn and Dec’23 corn, the fundamental supply and demand picture is vastly different between 2012 and 2023 as there is nearly 4% larger Stocks-to-Use ratio in 2023 than 2012 given the current lack-luster export, feed, and ethanol demand we have experienced for the current marketing year.

Other more bearish investors have noted that the current price trend is more similar to 1992 in which an early season drought induced volatility and rising prices. Contrary to 2012, the 1992 corn market saw a dramatic price decline after timely and significant rains busted the drought and produced a near trend-line crop yield.

So how does one effectively market a crop this year? The first step as always is to know the cost of production taking into actual input price figures to uncover an operation’s breakeven price and yield. Yield does play a critical role in determining these figures, though as we know yield is not the sole driver of profitability. Please refer to the University of Maryland Extension website for enterprise budget templates here: https://extension.umd.edu/programs/agriculture-food-systems/program-areas/farm-and-agribusiness-management/grain-marketing.

Certainly a next step would be to look for ways to offset future price risk. Depending on the level of familiarity, options strategies could offer additional downside protection. However, this is most commonly accomplished by forward contracting some of the new crop. At the time of writing, the soybean market continues to rise modestly above estimated cost of production figures for Central Maryland. Producers may find these prices profitable and would be well advised to limit potential downside risk.

Marketing professionals offer that producers may find shelter in short-run run-ups to sell new crop corn and stored wheat. Some analysts predict that the USDA may have to revise yield estimates lower given the potential damage done to the corn crop of the Midwest. The market may react to this revision lower, whereby the watchful marketer could capitalize on a small upward price movement. Yes it is tempting to wait for the next larger rally in the market, but waiting to find the top of the curve may prove far more risky than taking smaller profits. A wise farmer once said that he stayed in business for many years because, “I always took my profits too early.”

Source : umd.edu