Mike Grunwald’s latest excoriation of biofuels is a retread of the usual attack on farm-based fuels – based on the disproven notion that growing energy diverts food into fuel tanks and leads to the conversion of pristine lands. Taking a page from the climate denialism playbook, Mr. Grunwald relies on intuitive but fictional links, simplifies complex relationships into single variable deductions, and omits key information to build out his false narrative about U.S. biofuels. Ironically, many of the same influencers embracing Mr. Grunwald’s essay decried similar tactics deployed against electric vehicles just days before. Ideally, neither of these specious columns would make it through the journalistic integrity screens at The Guardian or The New York Times. But clicks are gold and sensationalism drives traffic. So, what did Mr. Grunwald get wrong?

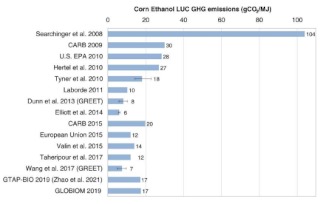

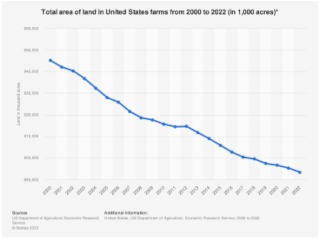

The U.S. “agricultural footprint” is shrinking (not growing). The linchpin to Mr. Grunwald’s thesis is that biofuels “increase greenhouse gas emissions through the conversion of carbon-rich forests, wetlands and grasslands into farmland, expanding our agricultural footprint while shrinking nature’s.” The problem with this argument is the U.S. agricultural footprint has been shrinking for decades, and more biofuel production over the past 15 years did nothing to change the trend. How could that be? Modern farm practices, which have increased yield-per-acre exponentially, have allowed U.S. agriculture to produce more product on less land. And, when ethanol demand grew (to replace the toxic gasoline additive MTBE), the market didn’t respond by clearing land to grow more corn. It responded by changing the way we use corn. The hard part about modeling land use change is accounting for market response. If you assume, as Searchinger did, that more biofuel demand requires more corn planting and that corn planting will occur on newly converted land, then your model will produce large carbon impacts. But if biofuel demand is met with higher yields and crop-switching, then the agricultural footprint doesn’t change and the carbon impacts, if any, are very small. In essence, Searchinger engineered an outcome to make an important point: that policymakers must be careful about knock-on effects. This is true for all energy types. But the resolution of the 2008 modeling is low and obsolete (assuming scientific integrity was ever the point). Mr. Grunwald doesn’t even mention the dozens of studies that have looked at the same question since 2008, with the more recent ones benefiting from 20/20 hindsight (i.e., the ability to root its conclusions in observed land use patterns during 2008- 2022 biofuel growth rather than uncertain forecasts produced by economic models). These higher resolution models have more data at their disposal and are more adept at accounting for dynamic market variables. The body of evidence shows that U.S. biofuel market growth has come without the land use change consequences claimed by Mr. Grunwald.