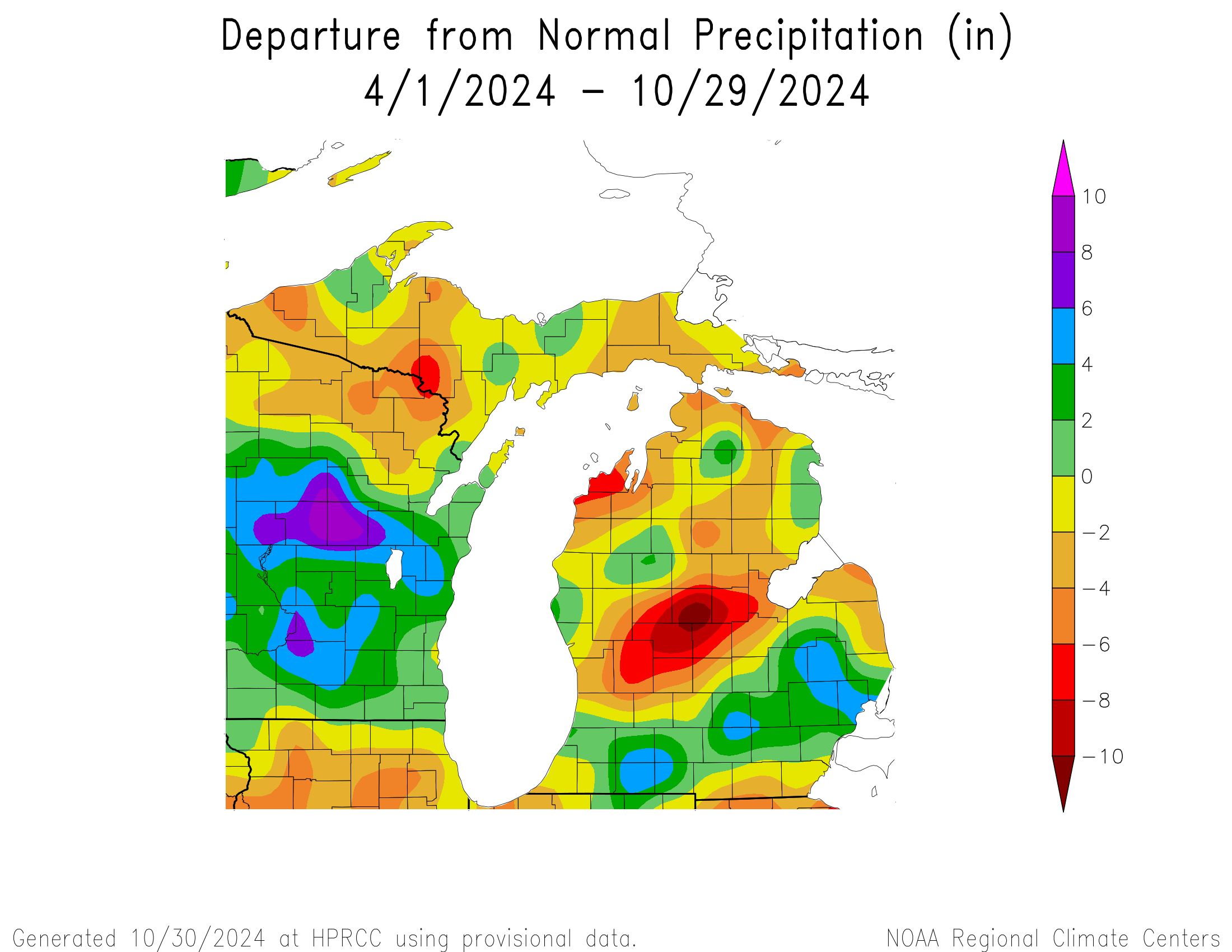

Early May was rainy with storms throughout the region. A tornado passed through Portage and Sherwood on May 7, affecting pivots, equipment and structures. Most corn, soybean and potato planting occurred between May 9 and May 30 as temperatures increased and many fields dried out. Late June brought significant precipitation and lower temperatures for a little over a week before warming back up again. The precipitation continued through early and into mid-July, hitting many areas just as soybeans were entering reproductive stages. These precipitation events led to several acres underwater. Wheat that wasn’t harvested before July 4 was delayed up to several weeks before harvest.

The warm weather continued, reaching a peak in late August when several days had heat indexes in the high nineties and beyond. Aug. 27 had a heat index of 105 degrees Fahrenheit. This time period was mostly dry, and several weeks with very little precipitation followed. The dry weather stressed some crops at critical kernel or seed fill stages but also facilitated drydown of early maturity group and early planted crops. Soybeans especially dried down faster than expected, with early harvests at moistures as low as 9%. Rainfall at the end of September evened moisture back out, just in time for a couple weeks of mostly dry, warm weather, and a lot of harvest, tillage and planting.

Finally, the temperatures cooled in the second week of October, leading to a frost in some areas. Despite the cooldown, many days in late October were still quite warm, reaching into the 70s during the day. The mostly warm and dry harvest contributed to several combine fires this season and low moistures on harvested corn and soybeans.

Crops and pests

Soybean

Soybean seeds and newly emerged plants faced an early pest in seedcorn maggot. This particularly affected fields planted early in cool weather closely following tillage. Future seedcorn maggot damage can be avoided by monitoring the seedcorn maggot model from Enviroweather. It predicts peak flights and can help plan planting for lower risk conditions. Some producers who suffered severe seedcorn maggot damage replanted acres. A cost to avoid in this scenario is treating the replanted seed. There is little benefit to treating the replant seed with insecticide, as the field is drier, warmer and less attractive to seedcorn maggot, and the warmer soil conditions will contribute to faster emergence.

High residue and no-till systems were strongly affected by slugs this year, leading to several acres being replanted. Slug feeding on soybeans primarily occurs on and below the cotyledon, resulting in total death to the seedling. Few treatment options are available for slugs. Iron phosphate (sold as Sluggo) and metaldehyde (sold as Deadline) are both labeled for slugs. However, metaldehyde (Deadline) has current restrictions in Michigan and Indiana that do not allow it to be applied on soybeans.

Although many soybeans were planted late, the high temperatures early in the season caused later planted plants to catch up quickly. Most soybeans entered reproductive stages in mid to late June. White mold began to affect fields in early August. As pods continued to develop, stink bug feeding was evident on seeds but not economic in most cases. High temperatures and dry weather increased instances of sudden death syndrome in some areas.

As the growing season came to a close, Michigan State University Extension pathologist Marty Chilvers warned to keep an eye out for red crown rot. Red crown rot is not currently confirmed in Michigan, but it is in Indiana and Illinois. The leaf symptoms are similar to those of sudden death syndrome, but the base of the stem has a red, slightly raised appearance. More information can be found in the article, “Red crown rot: A new threat to soybean production.”

Soybean harvest started early due to an aggressive drydown from prolonged high temperatures without precipitation. Some soybeans were harvested as dry as 6-9%. “Harvest considerations for overly dry soybeans” highlights potential economic and other factors to consider for harvesting soybeans at low moistures. Harvest wrapped up around mid-October on most soybean fields, and reported yields were variable. Some fields yielded better than ever while others were below average.

Corn

Like soybeans, some early planted corn faced pressure from seedcorn maggot, but infestations were less severe than for soybeans. Although many corn acres were planted late, the high temperatures early in the season caused later planted plants to catch up quickly. Sidedressed nitrogen applications began in late May and continued throughout June.

Western bean cutworm flights began in late June, but no significant populations were found in fields throughout the season. Corn that is close to tasseling or freshly tasseling is most attractive for egg laying female moths. According to Michigan State University (MSU) Extension specialist and field crops entomologist Chris DiFonzo, when scouting, put the sun behind the leaves and watch the upper third of the canopy for egg masses. It takes about a week for egg masses to hatch, at which point the larvae will travel to reproductive tissues. Larvae or their entry holes may be visible, but they hide to feed on reproductive tissues, so larvae can be difficult to see without opening up the plant. The threshold for western bean cutworm damage is 5% of plants with egg masses and/or larvae. This is a cumulative threshold, meaning that findings add up from week to week.

Detasseling for seed corn began around early July, and by mid-July, silks were starting to come out in commercial corn. Also in mid-July, tar spot was confirmed in Branch County, which was the first report of it in southwest Michigan. It was found in southeast Michigan in late June, much earlier than normal. Tar spot was later confirmed in other southwest Michigan counties, leading to a need for scouting fields. Chilvers recommended focusing on areas that might hold moisture, such as western tree lines or standing water under a pivot. Watch for the small, black, raised lesions of tar spot and use moisture to rub at the spots on the leaf to make sure they are truly lesions and not just insect frass (insect poop). The early finding of tar spot in 2024 raised concerns that it would be a year of heavy pressure, but in most cases, pressure remained light and had little effect on yields.

A sudden corn leaf aphid flight in late July surprised many growers with large populations of black winged and green wingless adults. They seemed drawn to specific hybrids, and in most cases, the aphids did not pose an economic threat unless they interfered with pollination.

Seed corn harvest began in early to mid-August, and commercial corn reached dent (R5) in some areas in mid-August. Earlier planted and earlier maturing corn hit black layer (R6) the first week of September. A few acres of commercial corn began harvest in late September with the majority of corn harvest occurring during October and continuing into November. Most field corn growers reported higher-than-average yields, with multiple growers breaking 300 bushels per acre in southwest Michigan. Seed corn harvest wrapped up for most producers around Oct. 20. For both seed and commercial corn, the late season heat without precipitation reduced the moisture content significantly. The lower moisture resulted in reduced drying costs, and some loads were taken off the field and put directly into long-term storage.

Winter wheat

After a wet fall in 2023 and late harvests all around, wheat was planted later than optimal. However, late planted wheat still tillered well due to sub-freezing temperatures also being late, not occurring until November 2023. Between the late sub-freezing temperatures, an overall mild winter and a high early accumulation of heat units, wheat was off to an early and green start in 2024. In mid- to late April, wheat reached Feekes 6 (jointing). At this stage, the stem elongates, and the growing point within the stem is above ground and more vulnerable to cold temperatures.

Jointing coincided with a drop in temperatures and a frost, which led to concerns that the frost might affect the wheat head and growing points. Signs of frost damage include sterile spikes, silage odor, stem bending and leaf tip burn. MSU Extension wheat systems specialist Dennis Pennington said that at jointing, wheat can survive temperatures down to 24 F for a few hours. Once wheat moves into boot stage, the threshold for frost damage becomes 28 F. There were several cases of leaf tip burn in southwest Michigan, but otherwise damage from the frost was very low.

Powdery mildew started up relatively early and was present in most fields, but in southwest Michigan it was generally not at a sufficient level for treatment. Stripe rust also broke out throughout the state, again mostly affecting other areas at higher pressures than in southwest Michigan. Some growers did apply fungicide treatments, especially as the flag leaf was emerging.

Wheat matured earlier than normal with heads emerging in mid-May and physiological maturity reached by the end of June. Growers who harvested before July 4, 2024, avoided the heavy precipitation that followed. This precipitation delayed harvest (up to several weeks in some cases), increased the risk of pre-harvest sprout and reduced kernel quality. By late July, nearly all wheat had been harvested. In mid-September, planting for 2025 began mostly on irrigated acres as the soil profile was very dry from weeks of warm and dry weather.

Forage

The mild winter and warm early temperatures led to an early outbreak of alfalfa weevil in mid- to late April. The threshold for early cutting of alfalfa at 16 inches or taller is feeding damage on 100% of stems and more than four larvae per stem. Young stands or short plants are not good candidates for early cutting, so if alfalfa weevil thresholds are hit, a spray application should be considered. The thresholds for plants 12-16 inches tall is more than 75% of stems damaged and more than two larvae per stem. For plants 9-12 inches tall, the threshold is more than 50% of stems damaged and more than one larva per stem.

Generally, cutting early is the preferred control method of alfalfa weevil. Weevils have many biological predators that keep them in check, and insecticides also kill beneficial insects in addition to pests. However, the early population in 2024 meant that many growers in southwest Michigan applied insecticide to manage populations because it was too early to cut alfalfa. More information on scouting for and deciding treatment thresholds of alfalfa weevil can be found in the article, “Weevils are popping in alfalfa fields.”

Potato leafhopper was another early alfalfa pest this year, arriving in late May. Potato leafhopper can severely damage tender regrowth and young seedlings. Populations should be monitored by sweeping, as damage is not visible until it is too late to treat.

Alfalfa and grass hay were sometimes cut at sub-optimal times this season. Alfalfa reached peak quality during a busy dry stretch of corn and soybean planting after several weeks of wet field delays. Heavy rains in early July also interfered with some cuttings, and then high temperatures and little rainfall slowed down regrowth at the end of the season.

Potato

Potato planting began earlier than normal in mid-March. Temperatures were high early season, increasing the risk of seed piece decay following planting. Planting was slightly behind previous years until early May, at which point it was delayed for several weeks due to rainfall and low temperatures. Potato leafhopper and Colorado potato beetle both appeared in fields in mid-May. In some cases, this was before planting had finished on all potato acres. Colorado potato beetle was about two weeks earlier than normal.

Flowering began in late May for early planted acres, and aerial applications began the last week of May, right around row closure. Aphids were found in early July, which is a little earlier than normal. Potato growers throughout the whole state reported higher aphid pressures than normal this year, and southwest Michigan was no different. Vine kill on early harvested acres began in mid-July, and fresh crop chip harvest began in late July.

Also in late July, late blight was confirmed by Rob Schafer of Mid-Michigan Agronomy in two different fields in St. Joseph County. The late blight was discovered in areas of the fields that received irrigation (over-application in one case) and poor fungicide coverage. In both cases, the disease was contained and appropriately decontaminated. Late blight is a highly contagious and destructive potato disease. Last year it was not discovered in St. Joseph County at all, and before that it was not found in commercial Michigan fields for a couple years. Late blight thrives in cool, moist conditions. Watch for it on lush canopies and field edges subject to prolonged leaf wetness.

Dry weather in September and October resulted in an earlier harvest than normal with several consecutive days of harvest. The high temperatures delayed harvest temporarily in some cases and increased bruise risk by drying out soils. However, a dry fall meant reduced disease risk for tubers going into storage. Overall, potato harvest finished up a little earlier than normal, and yields were reported to be good.

Water use

Early to mid-season weather in Michigan brought substantial rainfall and cooler temperatures, which significantly lowered irrigation requirements. Constantine received higher total precipitation than west-central Michigan; however, it experienced less rainfall from late August to mid-September than other locations. In general, all sites experienced reduced precipitation during this late-season period.

Typically, late August and early September bring cooler temperatures and increased rainfall, naturally reducing irrigation needs as crop water demand decreases. However, this year, many late-planted crops in Michigan continued to require high water into September due to evapotranspiration rates exceeding 0.2 inches per day. A late-August heat advisory brought hot to extreme temperatures, followed by several dry weeks. These conditions made late-season irrigation essential to support crop maturation.

Based on potential crop evapotranspiration, corn water use during early vegetative stages ranged from 0.3 to 0.6 inches per week. This demand increased during peak growth stages, including VT, silking, blister, dough and beginning dent, where water use reached 1.1 to 1.4 inches per week. As corn progressed from full dent to black layer, water needs decreased slightly to around 0.8 to 1.1 inches per week.

For soybeans, water requirements during early vegetative stages ranged from 0.3 to 0.7 inches per week, increasing during reproductive stages to about 1.1 to 1.4 inches per week. During late-season stages to early maturity, soybeans needed approximately 1 to 1.2 inches per week.

This season’s weather deviations highlighted the importance of adapting irrigation scheduling and management to meet varying crop water needs.

Source : msu.edu