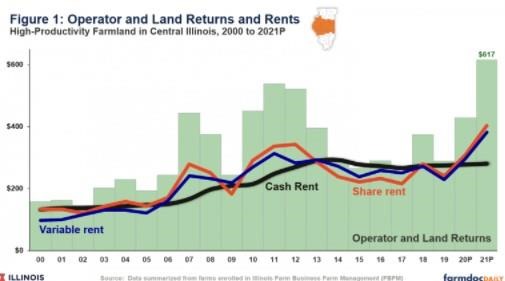

Figure 1 shows bars and three sets of lines:

Operator and Land Return: Operator and land return equals gross revenue minus non-land costs and represents a return to both the farmer and landowner. Under a cash rental situation, subtracting the cash rent from operator and land return gives the farmer return.

Operator and land returns for high-productivity farmland in central Illinois are shown as bars in Figure 1. Historical returns are summarized from farms enrolled in Illinois Farm Business Farm Management (FBFM). Revenues and costs before 2019 are reported in the publication Revenue and Cost for Illinois Grain Crops). The returns in Figure 1 were calculated using a 50% corn and 50% soybean rotation.

Cash Rent: This line represents the average cash rent for high-productivity farmland in central Illinois. Under a cash rental arrangement, the farmer makes a fixed payment to the landowner, with the payment level negotiated before the growing season (see Cash Rent Leasing Fact Sheet for more information). Under a cash rent, the farmer receives all revenues and pays all costs. Cash rents can vary tremendously across parcels for the same productivity of farmland. For each yearly average, there is at least a $50 plus and minus range around that year’s cash rent. For example, the average cash rent in 2019 is $275 per acre. There will be some rents $50 higher at $325 per acre and some rents lower at $225 per acre.

Share Rent: This line shows the average for a 50-50 share rent. Under a share rent arrangement, the farmer and landowner share in revenues and direct costs (see Share Rent Leasing Fact Sheet). All crop revenue, government payments, and crop insurance proceeds are split between the farmer and landowner. Direct costs that are shared include fertilizer, seed, pesticides, drying, storage, and crop insurance premium. Rents shown in Table 1 are calculated using a split of 50% to the landowner and 50% to the farmer, a typical arrangement for northern and central Illinois. Other splits, or additional terms to the lease, will cause different levels than shown in Figure 1.

Variable Rent: The variable rent line shows rent levels for one type of variable cash lease. There are many different types of variable rents, with a general characteristic that the cash payment varies based on crop revenue levels (see Variable Cash Rent Leasing Fact Sheet). For Figure 1, the landowner receives a 32% share of corn crop revenue and a 39% share of soybean crop revenue, resulting in an average split of 35.5% across both crops.

The 32% corn and 39% soybean splits were selected so that variable rents averaged the same level as cash rents from 2000 to 2021. The different splits between corn (32%) and soybeans (39%) were selected so that corn and soybean rent levels were roughly equal.

The variable lease in this example only includes crop revenue in its calculation. Government payments or crop insurance proceeds were not included in rental calculations. Splits used in variable rent leases vary across leases. As a result, those rents can vary from those shown in Figure 1.

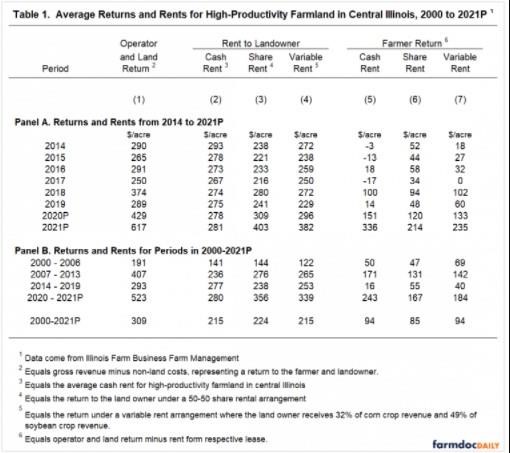

Data behind Figure 1 are shown in Table 1. Table 1 also shows average returns for periods described in the next section.

Lagging Nature of Cash Rents

Over the entire 2000 to 2020 period, operator and land return averaged $309 per acre. Rents from the three leases were relatively close to one another. Average rents were $215 per acre for cash rent, $224 per acre for share rent, and $215 per acre for the example variable lease. Note that the terms of the variable lease were set to achieve equality between the cash and variable leases.

However, the relationship between returns and rents varies over time. We divide the years from 2000 to 2021 into four periods:

- 2000 to 2006 — a period of lower returns.

- 2007 to 2013 — a period of higher returns because of growth in corn use in ethanol and robust soybean export demand.

- 2014 to 2019 — a period of lower returns.

- 2020 to 2021P — a period of higher returns due to higher prices .

2000 to 2006: From 2000 to 2006, corn-belt agriculture was in a period of relatively stable but low returns, with a great deal of support coming from government programs. From 2000 to 2006, operator and land returns averaged $191 per acre. Average cash rents and share rents were relatively close to one another, averaging $141 per acre for cash rent and $144 per acre for share rents. Variable rents lagged cash and share rents at $122 per acre (see Figure 1).

2007 to 2013: From 2007 to 2013, corn-belt agriculture was in an era of relative prosperity caused by growing corn use in ethanol and robust export demand for soybeans. From 2007 to 2013, operator and land returns increased to an average of $407 per acre, $216 higher than the $191 per acre average from 2000-2006.

Because the terms of the lease automatically adjust to higher returns, share rents and variable leases adjusted up. From 2007 to 2013, average share rents were $276 per acre, $132 per acre higher than the 2000-2006 average. Variable leases averaged $265 per acre, $143 per acre higher than the 2000-2006 average.

From 2007 to 2013, average cash rents increased each year, growing from $150 per acre in 2006 to $290 per acre in 2013. Still, average cash rent levels were lower than share and variable rents in all but two years (see Figure 1). In 2009, yield and prices were relatively low, resulting in low operator and land returns and share rents below cash rents. After years of increases, cash rent levels were on par with average share and variable rent levels in 2013: $290 average cash rent, $286 average share rent, and $293 average variable rent.

2014 to 2019: Returns to agriculture declined after 2013 (see Figure 1). The use of corn in producing ethanol stopped growing. Moreover, yields were good, leading to plentiful supply and lower prices. Operator and land returns averaged $294 per acre from 2014 to 2019, a reduction of $113 per acre from the $407 average for 2006 – 2013.

During the 2014-2019 period, cash rents declined slightly from $293 in 2014 to $267 in 2016. Over the period from 2014-2019, operator and land returns averaged $294 per acre, while cash rents averaged $277 per acre, leaving an average farmer return of $17 per acre, a marginal return for farming. There were several years where average cash rents exceeded operator and land returns resulting in a loss for the farmer: 2014, 2015, and 2017.

Share rent and variable rent levels reacted quickly and were below average cash rent levels in most years during this period. From 2014 to 2019, average cash rents were $277 per acre, while share rents averaged $238 per acre and variable rents averaged $253 per acre.

2020 to 2021: Operator and land returns are projected to average $523 per acre in 2020-2021, $230 per acre higher than the $294 average from 2014-2019 .

Average cash rents did not increase much from the 2014-2019 period. Average rents for 2020-2021 are projected at $280 per acre, only slightly above the $277 per acre level for 2014-2019. Both share rents and variable rents are above cash rents. Share rents are projected at $356 per acre and variable rents are projected at $339 per acre.

Commentary

Over the entire 2000 to 2021 period, rent levels for the three leases are relatively close to one another. Average rents were $215 per acre for cash rent, $224 per acre for share rent, and $215 per acre for variable leases. Note that the terms of the variable lease were set to achieve equality between the cash and variable leases.

While the 2000-2021 averages are close to one another, yearly rents vary across the leases. In general, cash rents have lagged changes in returns. Cash rents did not go up as fast as returns during the 2006-2013 period, nor come down with lower returns from 2014-2019. Cash rents did not rise much in 2020 and 2021. In contrast, share and variable rents adjust more quickly to changes in return levels.

Given history as a guide, higher returns in 2020 and 2021 likely place upward pressures on cash rents. Whether that is justified depends on perspective. At average cash rent levels, farms had low and negative returns from 2015 through 2019, and the higher returns in 2020 and 2021 could be viewed as a period of catch up. Average farmer returns for 2014-2021P for cash rents still are lower than average returns from share rents, and a period of lower commodity prices after 2021 could cause farmer returns to fall again.

Current cash rent level is also a factor. Cash rents vary from parcel to parcel. Those rents that are below average have more justification for an increase. Conversely, higher current cash rents have less justification.

It seems likely that cash rents will always lag adjustments in returns. If this is a concern, use of a share rent or variable lease will cause faster adjustments, both up and down.

This article has used projections for 2021 and much can happen between now and harvest. How much upward pressures exist on cash rents for 2022 and beyond will depend on whether projected current higher prices hold through the fall.

Source : illinois.edu