As the discussion below clarifies, problems with this policy design result from Congressional decisions in establishing the payment thresholds (e.g., reference prices) at different rates or levels. When Congress elects to establish a payment threshold for some program crops at higher levels than others, the consequences on the ground are that farmers with base acres in those favored crops receive larger payments while being able to plant other crops on their farms.

As review, PLC payments are triggered when a crop’s Marketing Year Average (MYA) price is below the Effective Reference Price (ERP) for the program crop, with the ERP being the higher of the Statutory Reference Price (SRP) or 85% of the five-year Olympic moving average of MYA prices (not to exceed 115% of the SRP). When MYA is below ERP, the difference (or deficiency) results in a payment rate, which is multiplied by a fixed program yield and paid on 85% of the program crop’s base acres. The disparities in reference prices, as they play out through base acres versus planted acres, result in significant differences in support levels for farmers in different regions. For example, the most recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections would average PLC payments of $120 per base acre for peanuts, $58 for all rice, $30 for seed cotton, $29 for corn, $10 for wheat, and $6 for soybeans (CBO, February 2024; farmdoc daily, May 14, 2024). A farmer with base acres of a high payment crop like rice or peanuts can receive the larger payments without incurring the costs or risks associated with those crops, while planting a crop like soybeans with lower relative costs and risks.

Discussion

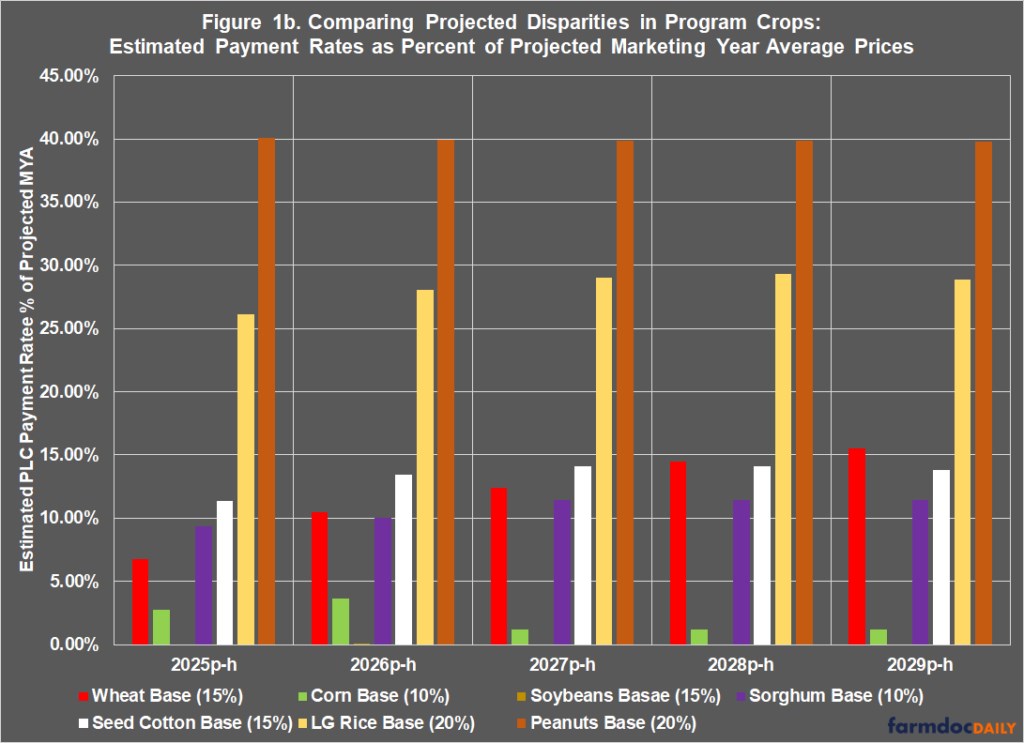

The recent Title-by-Title Summary of the proposal in the House indicated that all crops would receive an increase in statutory reference prices between 10% and 20% (7 U.S.C. §9011). The likely result from this will be different rates of increase by crop and, if history is any indication, the largest increases are likely going to rice, peanuts, seed cotton and other smaller acreage crops, while smaller increases will be applied to the larger acreage program crops of corn, wheat, and soybeans. It is possible that soybeans could be an exception because current reference prices are significantly below market prices and a larger percentage increase would not have the same cost implications.

The discussion that follows uses the following assumptions for the level of reference price increases for the major program crops: highest level (20%) for long grain rice and peanuts; mid-level (15%) for wheat, soybeans, and seed cotton; lowest level (10%) for corn and grain sorghum.

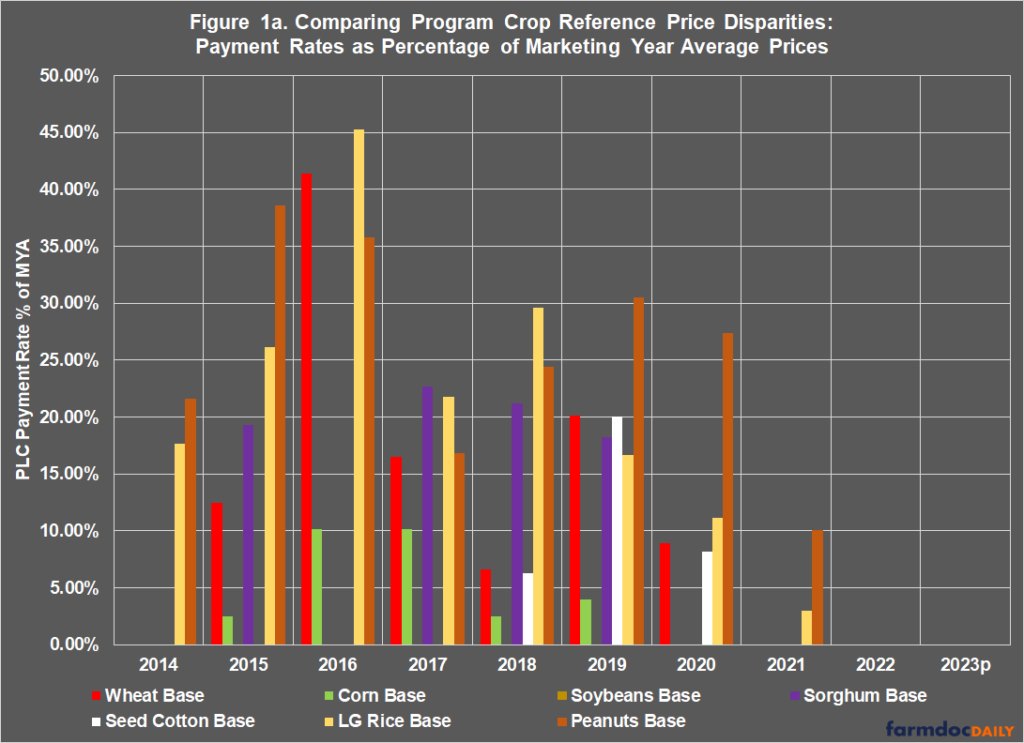

Figure 1a illustrates the differences among current reference prices based on the actual payment rates under PLC since 2014 as reported by the Farm Service Agency (USDA-FSA, ARC/PLC Program Data). Figure 1b illustrates the differences if the House proposal were enacted for crop years 2025 to 2029 (presumably those covered by a 2024 Farm Bill), using the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections for MYA prices in the February 2024 baseline update (CBO, February 2024). The comparison here is the PLC payment rate as a percentage of the actual or projected MYA for each program crop. Note that CBO reports only an all-rice MYA and the MYA used throughout is based on the historic relationship between the all-rice and long grain rice MYA.

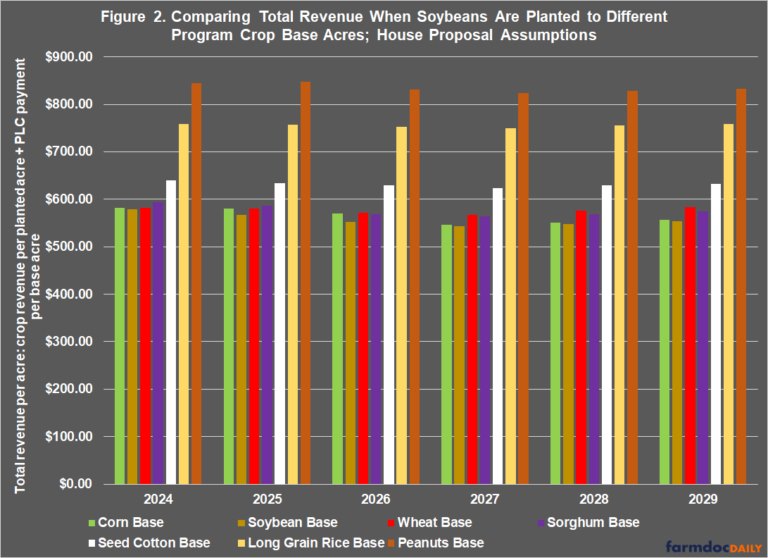

Figure 2 illustrates what happens when farmers plant soybeans on base acres for each of the major program crops under SRP increases at the different levels noted above. Figure 2 uses the price, yield, and PLC program yields reported by CBO in the February 2024 update to compare total revenue across program crop base acres for the presumed 2024 Farm Bill (crop years 2025 to 2029). The total revenue equals the projected PLC payment for each program crop base acre (factored by 85%) added to the national average revenue for soybeans per acre planted. Farmers in this scenario are planting the same crop (soybeans); farmers who plant soybeans on base acres for peanuts, long grain rice, and seed cotton would receive significantly more total revenue per acre (soybean revenue plus PLC payment per base acre) compared to farmers planting soybeans on the base acres of the other major program crops, especially soybeans.

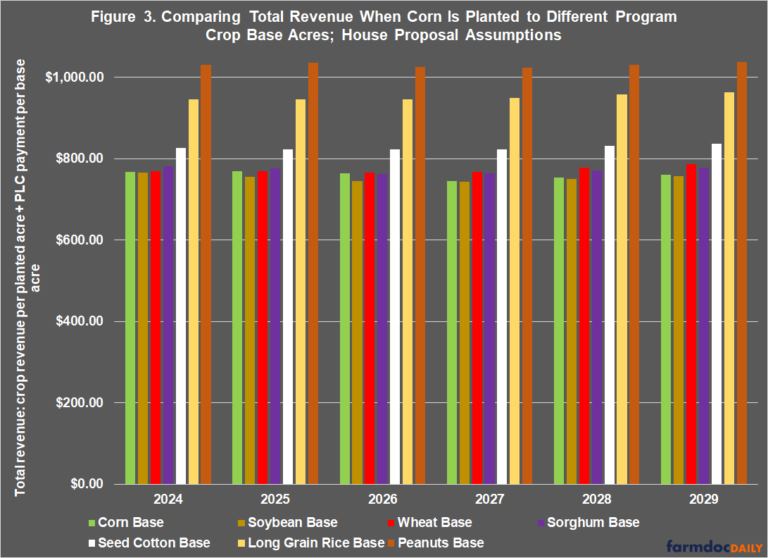

Figure 3 illustrates the same scenario for farmers planting corn on different program crop base acres and thus receiving the corn revenue per actual planted acre and the PLC payment for the alternative program crop base acre.

Both Figures 2 and 3 present scenarios much closer to the farmer’s perspective as compared to the baseline or CBO cost projection perspective discussed previously (farmdoc daily, May 14, 2024). The differences in reference prices on base acres translate into different total revenue for farmers who plant the same crops but have different base acres on the farm because the payments on base acres are disconnected from the costs of the crop planted and the risks in producing it. This has been the experience for farmers under PLC since it was first enacted in 2014 as provided in Table 1.

A comparison that results in 100% would be those years in which the program crop did not receive a PLC payment and the farmer’s total revenue would be the planted crop revenue (soybeans or corn). A comparison that results in less than 100% would be a year in which corn base received a PLC payment but the alternative program crop did not (e.g., planting corn on soybean base). In most years, farmers with peanuts, long grain rice, and seed cotton who planted soybeans or corn received significantly more total revenue than farmers with other program crop base. If Congress elects to increase reference prices by different levels for the program crops and leaves base acres unchanged, it is highly likely to increase these disparities.

Concluding Thoughts

ARC and PLC are unique among all farm policies in that the programs are designed to have payments that are decoupled from current planting decisions made by farmers. For crop insurance, the farmer pays a portion of the premium for an insurance policy on the actual crop planted and for which the costs are incurred, as well as the risks. With conservation assistance, the farmer or landowner receives a payment in return for adopting conservation practices on the farm. When disparities in payment thresholds are enacted by Congress, the impacts are different for farmers depending on which base acres the farmer has on the farm. Farmers can plant the same crops, face the same prices, incur the same production costs, and manage the same risks but receive very different payments and thus different total revenue. This issue is largely ignored in the Farm Bill deliberations because of the priority given to CBO cost projections whereby relatively small payments for crops with large amounts of base acres (corn, soybeans, and wheat) have much higher scores than relatively large payments for crops with small amounts of base acres (seed cotton, rice, and peanuts). These cost projections are irrelevant to farmers, however, because the per-base-acre payment amounts are what they receive as part of their farm’s revenue.

Source : illinois.edu