2. Reduce Herd Size

Another option to reduce feed costs is to simply feed fewer cows. With lower stocking rates, pastures can provide more forage per acre for the cows that remain. This herd reduction would have to be substantial enough to make a real difference, not just a 5 to 10%. Reducing the herd 25-50% will reduce the pressure on pastures as well as hay fields. If pastures were stocked to the maximum limit during high cattle prices, it may be time to sell of some off the poorer performing, older cattle to reduce costs. As the market improves, additional cattle could be purchased to rebuild the herd again later on. There is an obvious problem, however; fewer cows results in fewer calves to sell, and even lower income. Fixed costs per cow, such as hay equipment, tractors, and trailers, will actually increase because there will be fewer cows to share these costs. If you are operating at or near breakeven at this point, however, it is better to keep fewer cows and still provide adequate nutrition than to just feed less to the current herd just to save money. There are immediate consequences for inadequate nutrition. Reproduction is the last system supplied energy when energy is in short supply, so cows will remain open longer in the breeding season, until pastures grow enough to make up the short fall. The cows immune system can also be depressed, if energy needs are not met. In the end it is better to feed and graze fewer cows than to just cut back to save money.

3. Targeted Pasture Fertilization

One expense that always seems to be a focus is fertilizer costs. Since pasture fertilizers are most commonly ordered all at one time each spring, this is normally one of the largest single bills to be paid. In general, fertilizer is the largest annual expense for pastures. There are some things that can be done to reduce the fertilizer bill. Soil testing is more critical than ever to ensure that only the limiting nutrients are applied with each fertilization.

One area of pasture fertility that should not be eliminated is soil pH maintenance. In the chart to the right, the widest parts of the bars represent the pH when each nutrient is most available and useful to plants in the soil. On the very first line of the chart you can see that when the pH drops below 5.0, nitrogen is less available to the plant. In other words, at lower soil pH no matter how much fertilizer you apply, less is utilized by the plant. If there is not enough money to cover the expense of lime and fertilizer for every acre of pasture that needs it, the lime should not be skipped. Send in those soil tests and make sure the pH stays above 5.5 for optimal forage growth. If soil test results indicate lime is needed, then apply it, don’t skimp on lime.

Put your money where you will get the greatest return. Spring fertilization provides greater returns than in late summer. Nitrogen (N) is the “Gas that makes grass grow.” No other nutrient provides the yield boost that nitrogen fertilization does. It is be better to only fertilize your most productive pastures with 50 lbs.N/acre in the spring, than to fertilize double the acreage with only 25 lbs.N/acre. At 25 lbs.N/acre your weeds will grow faster than your grass. Just make sure to record which pastures were fertilized, so you can pick up the others in the years ahead.

If you decide to use the 50 lbs.N/acre rate on bahiagrass pastures, UF/IFAS recommends no potassium, and only 25 pounds of phosphorus per acre when the soil tests low for P205. (This is not the case for hay production, where these nutrients are removed from the field with every cutting.) You can also save money utilizing poultry litter as the source of this nitrogen, instead of conventional fertilizer. Just be mindful of the odor and the impact it can have with neighbor relations.

More detailed information on this subject is available in the publication Fertilizing and Liming Forage Crops. If you decide to cut out pasture fertilization all together this year, be aware the weeds will have a competitive advantage, and will eventually take over. You also will need to adjust reducer stocking rate, because unfertilized pastures are much less productive, and will take longer to recover after grazing.

4. Grazing Management

One area of ranch management that is often overlooked is grazing management. The photo above shows the difference in root growth from Bahiagrass that was never grazed, mob grazed with 21 days rest, grazed down to 50% every three days, or grazed off continuously every three days. If cattle stay in the same pastures continuously they will selectively eat the tender growth and force forage plants to shed some of their roots to survive. Eventually the grass will die out and invasive weeds and grasses, such as centipede and broomsedge will take their place. The old rule of thumb for grazing is “Take Half and Leave Half.” The idea is to graze forage down halfway and move them to a new pasture. This photo shows why that is so important. You don’t have to build an intensive grazing system with 22 paddocks and daily rotation for each herd, but you can certainly improve the efficiency of a pasture by rotating cattle more frequently.

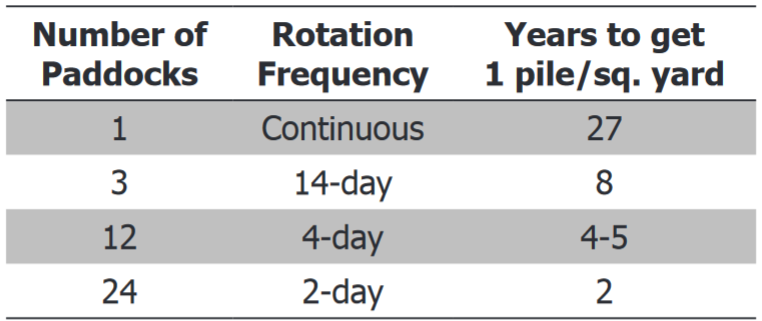

Not only does rotational grazing benefit the health of forage plants, but it also provides better nutrient recycling through more even manure distribution. Keeping cattle from congregating in the same places each day distributes the nutrients around pastures more evenly. Unlike the situation with hay production, very little nutrients are lost in the form of weaned calves leaving the farm. With more regular rotation, nutrients added from feed and fertilizer are more evenly redistributed in manure. While moving cattle to a new paddock every two days may not be feasible in your operation, this study does demonstrate the concept well. The more often cattle rotate and graze a new paddock the more efficiently pastures can be utilized. More frequent pasture rotation does require more labor, but the benefits of more productive, and healthy forage plants, and the more efficient recycling of feed and fertilizer nutrients are worth the extra time required.

Summary

The four management options discussed in this article are just a few of the concepts worth evaluating in the publication, Cutting Costs, Not Corners: Managing Cattle in Tough Times. The take home message is to not just spend less, but instead develop a well conceived cost cutting plan for your operation. Profitability in a deflated market is a sizable challenge to overcome, but there are options worth considering as you work through this challenge.

For ideas on making the most of your investment in hay production, check out this article, previously published in Panhandle Ag e-news: Improving the Efficiency of Your Hay Production

Source:ufl.edu