Given the outcomes of the election, no action on Congress reauthorizing the Farm Bill in the lame duck session. A majority of American voters placed their bets on Republicans in the 2024 election, with the party winning a trifecta (regaining the Presidency and a Senate majority, while retaining control of the House of Representatives). A bill with billions of dollars in food and agricultural policy for the next five years is not in the cards. Another year-long extension will kick the can down the road and punt the matter to the next (119th) Congress, where the prospects are difficult to predict. To handicap Farm Bill reauthorization, the discussion detours through a review of budget reconciliation and a few slices of history.

Budget Reconciliation

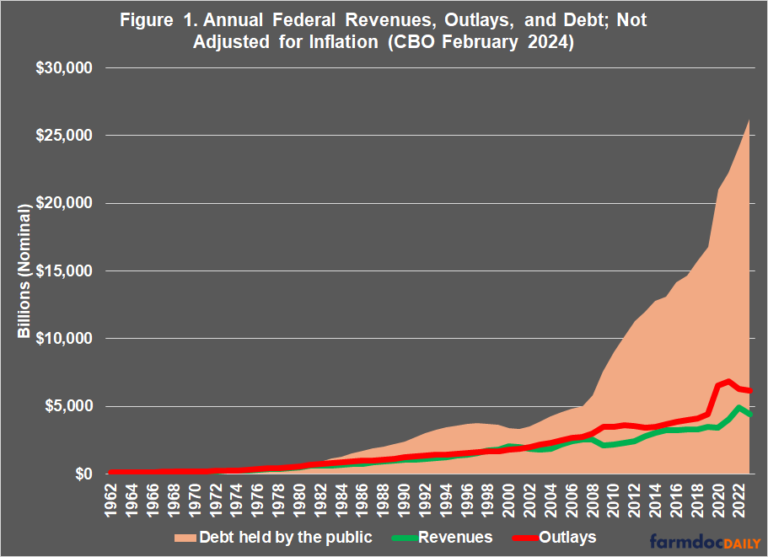

Budget reconciliation was created by Congress in 1974, designed as a method to revisit budget and spending matters near the end of the fiscal year and allow Congress to make revisions due to changed circumstances (P.L. 93-344, Sec. 310). Federal budget law continues to authorize reconciliation, but it now works via instructions in a concurrent budget resolution between the House and Senate (2 U.S.C. §641). If Congress includes reconciliation instructions, committees report legislation to meet them which are compiled into a single, omnibus legislative vehicle that is considered under special rules. The legislation receives fast-track consideration in both chambers; in the Senate, this alters the rules for debate and filibuster, meaning it can be passed by that chamber without the 60-vote cloture requirement. Reconciliation legislation does, however, need to comply with specific rules, such as not including anything extraneous to the budget, or changes in outlays and revenues (2 U.S.C. §644). Budget discipline and control has failed for its purpose as illustrated by the federal revenues, outlays, and debt in Figure 1 (CBO, February 2024).

The fast-track nature of budget reconciliation has increased its appeal to an increasingly polarized and dysfunctional Congress. In the 2020 elections, for example, Democrats won the Presidency and majorities in the House and the Senate. With that trifecta, they enacted the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 using budget reconciliation, a kind-of novelty bet that used reconciliation instructions to increase spending to meet various policy goals related to climate change and energy incentives (see e.g., Ramseur, October 26, 2023; farmdoc daily, August 11, 2022).

Perspectives from History

If history is a vast reservoir of valuable context and important perspectives, working backwards through time can unearth some from moments when reconciliation intersected with the Farm Bill. The 1994 midterm elections were a previous electoral earthquake, as Republicans won a House majority for the first time in 40 years. The 104th Congress also featured a Republican Senate majority (53 Republicans to 47 Democrats). The united Republican Congress tried to parlay its midterm victories into major changes in federal policy and spending using budget reconciliation but ran into a procedural wall, the veto of Democratic President Bill Clinton. The effort eventually produced the landmark Federal Agricultural Improvement and Reform (FAIR) Act of 1996. Before that, the 1990 Farm Bill reauthorization was split with budget reconciliation hammered out between Democratic majorities in Congress and Republican President George H.W. Bush. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 was projected to cut between $13 billion and $14 billion (over five years) from the Farm Bill (Pollack and Lynch, 1991; Collins, Salathe, and Hudson, 1990 or 1990; Coppess, 2018). But the most interesting historical example is 1981. Ronald Reagan defeated a sitting President in a time of high inflation, with coattails that helped Republicans flip the U.S. Senate. Republicans won 12 seats from Democrats to secure a 53 to 47 majority, their first since 1952 (CQ Almanac, 1980; see also, Kilgore, November 11, 2024). The electoral flood did not change control of the House, however.

Reagan’s victory has been labeled a revolution for having toppled the New Deal, ushering in the neoliberal order that may have ended with the 2024 election (see e.g., Gerstle, 20018). David Stockman, Reagan’s Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), best personified the new ideological and revolutionary spirit (White and Wildavsky, 1989; farmdoc daily, March 16, 2017). In the book he wrote after he left the Administration, Stockman described a “stunningly radical theory of governance” under which Congress would have to “surrender,” or “forfeit its independence and accept the role of a rubber-stamping parliament.” He added that the “constitutional prerogatives of the legislative branch would have to be, in effect, suspended” and the “world’s so-called greatest deliberative body would have to be reduced to the status of a ministerial arm of the White House” (Stockman, 1986, at 159 and 200).

As Reagan’s lead negotiator, Stockman’s gamble was a bold strategy to pair massive tax cuts with equally massive cuts in federal spending and programs. According to Stockman, the “worst nonsense of all in the budget, of course, was farm subsidies” and he included it for cuts, arguing that farmers “had never been the same after the New Deal turned the wheat, corn, cotton, and dairy business into a way of life based on organized larceny” (Stockman, 1986, at 152-53). His strategy rested on destroying the coalition, beginning with food assistance programs and then individually attack each commodity program; or, as he explained to William Greider, the plan was to “come in with a farm bill that’s unacceptable to the farm guys so that the whole thing begins to splinter” (Stockman, quoted in Greider, 1981).

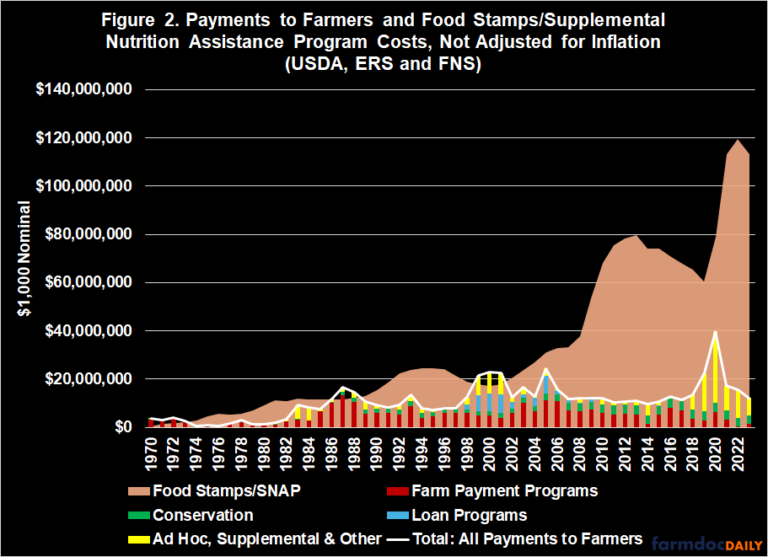

For Stockman and the revolution, the strategy both worked and failed, a Pyrrhic victory that traded away the ideological, revolutionary goals for votes in a divided Congress. Moving Reagan’s tax and budget plans required cutting a deal with a faction of Southern Democrats known as the Boll Weevils. The Southern vigorish was protection of subsidies for the southern commodities, cotton, rice, tobacco, and peanuts, which led Congress to protect all commodities, increase target prices, and avoid cuts to Food Stamps (Stockman, 1986, at 154). Looking back, Stockman wrote that those deals “proved that the White House couldn’t even tackle the fabulous excesses of the farm pork barrel,” and because the “single cleanest, easiest, and most justified shot at budget cutting during the entire Reagan presidency was kicked in the ditch” meant “nothing, but nothing, could be done about federal spending” (Stockman, 1986, at 383-86). Figure 2 illustrates total spending on farmers (payments, conservation, and ad hoc or supplemental payments) and spending on food assistance (Food Stamps and SNAP).

Handicapping Farm Bill Reauthorization

When the deal comes around in 2025, Republicans will be holding all the cards but Stockman’s gamble haunts ideological revolutionaries with reminders of how fleeting and fickle political momentum can be. Next year won’t be a rerun of 1981; if nothing else, there is a significant difference between a President facing an opposition party in control of the House and one with a governing trifecta. History does not repeat but it can inform, and with history as bookmaker, the following are some odds on what may unfold:

- Odds-on favorite: the 119th Congress to use reconciliation to enact tax cuts that are coupled with significant spending reductions, including substantial cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Inflation Reduction Act, including remaining conservation program funds.

- A prop bet: Congress block grants SNAP to the states with funding caps, which allows Congress to dodge unpopular program changes, handing off the problems to State governments, especially the large population states with Democratic Governors.

- Off the board: If reconciliation cuts SNAP and IRA/conservation, the odds for reauthorizing farm payment programs and the rest of the Farm Bill in a regular order process are too uncertain.

- Longshot: Reconciliation includes much of the Farm Bill reauthorization with significant reductions to conservation programs, farm payment programs, and crop insurance (premium subsidies and Administration & Operating subsidies).

- Even money: Reconciliation includes significant cuts to SNAP and IRA, while increasing farm program payments (e.g., increasing reference prices) and crop insurance.

While regular order for Farm Bill reauthorization in the 119th Congress cannot be ruled out at this time, it won’t happen before budget, tax, and debt ceiling matters are resolved. Should the Farm Bill’s mandatory programs escape reconciliation, the state of play in Congress and the capital will need to be reassessed to determine reauthorization’s chances.

Concluding Thoughts

For those inclined to take a deeper dive, Greider’s article is worth the read. There is much there for the curious, and the committed. Stockman went into the effort with revolutionary idealism despite having served four years in Congress. If he was being honest, he presented a fascinating working theory for the conservative ideology fueling the Reagan revolution. Framed as “curtailing weak claims rather than weak clients,” he argued it was “critical” to “both political and economic success” for the Reagan conservatives to be “willing to attack powerful clients with weak claims” (Stockman, quoted in Greider, 1981). But within the year, he conceded to a very different reality about the political power of “these client groups” that “know how to make themselves heard” while the “unorganized groups can’t play in this game” and “weak clients suffered for their weakness” (Stockman, quoted in Greider, 1981).

That change provides lessons about factions for anyone interested; his education in 1981 echoed lessons articulated from the Framers of the Constitution forward, such as Mancur Olson in the 1960s and Herbert Hovenkamp in modern iterations (Olson 1965; Hovenkamp, 2016; see also, Coppess 2024, at chapter 10; farmdoc daily, November 11, 2022; January 5, 2023; January 26, 2023). But Stockman arguably made the asymmetrical power dynamics worse by helping modify budget reconciliation, which significantly magnified the power of smaller, more organized factional interests. The enormous, omnibus nature of reconciliation legislation makes it easier for smaller factions to negotiate favorable outcomes for themselves, which are miniscule in the overall budget numbers, while larger interests are at more of a disadvantage under the budgetary burdens and up against fast-track procedures—the reconciliation process he helped create was the very thing that undermined the revolutionary ideological goals he initially proclaimed.

This fundamental reality provides an important lens through which to evaluate what unfolds next. To the extent that American voters sought a counter-revolution to the neoliberal Reagan revolution (itself a counter-revolution to that of the New Deal), their bets have been placed and the race is on. Stockman’s original working theory about weaker clients with stronger claims and stronger clients with weaker claims remains an interesting framework for assessing who wins; as in 1981, the odds are stacked against the former and in favor of the latter. It is possible that the outcome for the Farm Bill’s mandatory programs, in the treatment of food assistance programs and farm assistance programs, will go a long way towards determining the ultimate costs and consequences of the American voters’ bet. Reality has little use for ideology; curtailing assistance does not end hunger or poverty, nor does it reduce weather and market risks. When the deal goes down, the losers may be left with little more than metaphors for a song.

Source : illinois.edu