On the Market

The Politics of Pulse Prices

Events unfolding on the world’s political landscape will probably have a profound effect on the average prices of pulses and other field crops in the coming season and beyond.

In Canada, the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) will no longer be the sole buyer of wheat, durum and malting barley as of August 1, 2012. In the United States (U.S.), there is a good chance biofuel subsidies will be reduced, while subsidies to farmers could be enriched in the Farm Bill, which will be crafted by Congress and the Senate next year. Meanwhile, lack of confidence in certain nations’ abilities to meet their financial obligations is contributing to volatile currency markets. All these factors are creating concerns for buyers, who are worried about owning more product than they need to cover short-term needs.

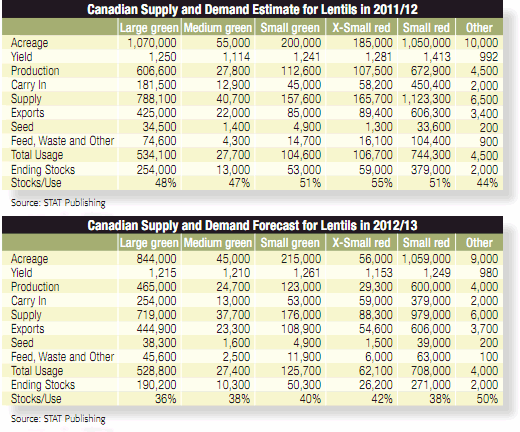

I discussed the possible impact of the changes in the CWB in the November edition of the Pulse Market Report. The bottom line is competition for land use is likely to increase as wheat, durum and malting barley become cash crops. Canola crops have tended to be competition for pulse crops in terms of land use, while grains have tended to be just another crop in the rotation. This will change as farmers will now be able to take advantage of the same kinds of new crop pricing and delivery opportunities as they do with canola.

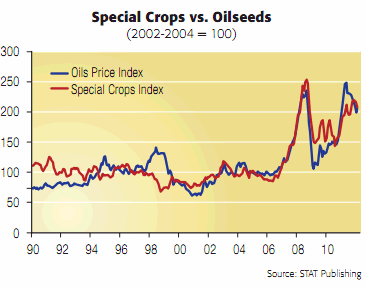

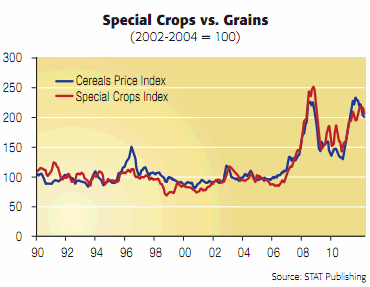

The fact that pulse markets now need to pay closer attention to the income potential of a wider range of crops than in the past reflects a simple truth: As much as possible, farmers grow more of the crops that have the best income potential. To the extent acreage for acrop needs to stay the same or increase, grower bids need to be at levels that offer returns that are competitive with better-performing crops. As a result, when grain and oilseed markets are strong, bids for pulses may need to rise to keep farmers interested in growing them.

The opposite is true from a consumer’s perspective. While farmers want to maximize revenue, consumers want to minimize costs – to the extent they are willing to substitute one pulse or type of food for another, in order to be able to buy the most food for the least cost. If wheat and durum prices decline, some consumers may eat more pasta and fewer pulses. Similarly, if feed grain or protein meal values drop, meat might become cheaper and therefore preferable to pulses.

Competition for land use and for consumer attention means that field crop prices tend to follow one another. This means that any factor affecting the price of corn will ultimately affect the price of lentils, peas and chickpeas.

This was made clear in 2006 when markets began to understand the impact of U.S. biofuel policies on demand for corn for ethanol, and vegetable oil for biodiesel. The resulting competition for land use forced prices for pulses higher in order to prevent production from collapsing. Now, it is clear that U.S. biofuel policy is going to change. There is a growing push to eliminate the 45¢/gallon subsidy to ethanol refiners in the U.S. and to repeal or reduce the 54¢/gallon tariff on imported ethanol.

At the time of writing, both the subsidy and the tariff were set to expire on December 31. Even if there is a last-minute extension, there seems to be little will in Congress or the Senate to continue the policy because of the multi-billion-dollar price tag. Uncertainty over the subsidies and the import duty are one of the reasons corn prices have weakened. The March ‘corn futures,’ for instance, was more than $7/bushel most of August and the first half of September, but was less than $6/bushel for most of December.

If the subsidy and import duties are extended, the 2012 election may determine whether they will remain in effect after 2012, along with biofuel mandates. There is bipartisan antagonism toward subsidized ethanol production. Moreover, if it can be freely imported from Brazil, ethanol prices could drop, which would affect the price of corn. If corn prices drop, soybean, wheat and durum do not need to be as high to attract acreage, allowing those markets to ease. If those prices decline, the income potential of pulses would look a lot better and it would be easier to grow too many pulses. So, those markets would likely drop.

The other major uncertainty facing markets is the fate of the U.S. Farm Bill. There is fundamental disagreement over the Farm Bill, with many “Tea Party” Republicans wanting to scrap all forms of price and income support. Others argue that doing so would put the U.S. food supply at risk. While untrue, eliminating price and income support programs would result in a difficult transition to a fully market-driven economy for American farmers. It is beginningto look like there will be higher minimum support prices for commodities covered by the U.S. Farm Bill.

This is not a bullish development. Should markets drop below the support levels in the U.S. Farm Bill, U.S. farmers will more often ignore the market when deciding what to grow. This can result in over-production of corn, driving down the value of protein meals in livestock feed and reducing the price at which wheat effectively competes for land use in the U.S. This should result in lower meat prices, creating downward pressure on pulse values.

The cure for high prices is high prices. The cure for low prices is low prices. But when government policies and programs help bring about either condition, it becomes harder for markets to work the way they should. Like it or not, the political struggles and attempts at deficit cutting in Washington may have a profound impact on the price of lentils, peas, and chickpeas in 2012/13 and beyond.