The last farm bill passed by Congress, the 2018 Farm Bill, originally ran through the 2023 commodity year. It was extended for the 2024 year (farmdoc daily, September 12, 2024). As of yet, the 2018 Farm Bill has not been extended into the 2025 year but is likely to be extended in a lame-duck session after the elections. Alternatively, Congress could pass a new farm bill which would be expected to cover the 2025 through 2029 crop years. These alternatives are discussed below.

Extending the 2018 Farm Bill: In its June 2024 projections of mandatory agricultural spending, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates payments from the 2018 Farm Bill for commodity program through 2033. Payments for 2023 have just been announced. Table 1 shows projected Commodity Title payments per base acre for the 2024 and 2025 commodity years. These payments are averages of PLC and ARC payments. CBO estimates these using simulations that consider a wide range of yield and price combinations (see e.g., Regmi and Kuethe, 2024).

Most farmers will not receive commodity title payments from the 2023 commodity year. PLC will not make payments on corn, soybeans, wheat, seed cotton, and peanut base acres as market year average (MYA) prices are above effective reference prices. ARC at the county level, will make payments on base acres in some limited instances. Commodity payments for the 2023 crop will be made soon. Again, most farmers will not receive payments.

For the 2024 commodity year and 2018 Farm Bill, CBO projected payments of $16 per base acre for corn, $3 for soybeans, $4 for wheat, $13 for seed cotton, $80 for peanuts, and $80 for long-grain rice (see Table 1). These CBO estimates suggest that the commodity title will provide significant support for peanuts and long-grain rice and less for corn, soybeans, wheat, and seed cotton. Midwest farmers have a blend of corn and soybean base acres and will receive significantly less than farmers with base acres of peanuts and long-grain rice. Moreover, because these payments are made on base acres, not planted ones, the relative payments to Southern farmers are understated by the CBO per base acre estimates because peanuts and rice have significantly more base acres than planted acres. Importantly, the estimates remain uncertain for any payments for the 2024 crop year. If support is triggered, the Farm Bill pushes payments into October of the following years and such payments will not be received until October 2025.

CBO also estimates commodity title payments for the 2025 crop year assuming that 2018 Farm Bill programs continue with their current design. Notably, the current design of PLC includes an escalator provision that will increase the effective reference price for many of the program crops (see farmdoc daily, October 5, 2023). Based on CBO outlay projections, the estimates for 2025 program crop payments are $34 per base acre for corn, $11 for soybeans, $6 for wheat, $19 for seed cotton, $118 for peanuts, and $110 for rice. Those payments are expected to be higher than projections for the 2024 crop year but will not be received until October 2026.

Passing a New Farm Bill

If Congress is to reauthorize the Farm Bill, it must do so in a lame-duck session. The Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry has not produced or reported legislation. The House Agriculture Committee reported legislation in May but it has not been considered on the House floor (H.R. 8467). For farm payment programs, the House Agriculture Committee bill would:

- increase statutory reference prices for all program crops and

- increase the ARC guarantee from 86% to 90% and the ARC payment range from 10% to 12.5%

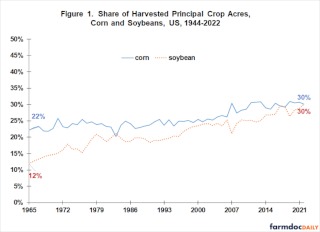

Those changes would apply in the 2025 commodity year, with the 2025 payments occurring in October 2026. Figure 1 shows CBO estimates of 2025 payments under the 2018 Farm Bill. We provide expected program payments for the House Agricultural Committee’s draft relative to an extension of the 2018 Farm Bill:

- Expected corn payments per base acre for the 2025 crop year would increase from $34 under the 2018 Farm Bill to $43 per base acre under the House Ag Committee’s Bill, a 26% increase.

- Expected soybean payments for the 2025 crop year would increase from $11 to $17 per base acre, a 55% increase.

- Wheat payments would increase from $6 to $14 per base acre, a 133% increase.

- Seed cotton payments would increase from $19 to $60 per base acre, a 216% increase.

- Peanut payments would increase from $118 to $269 per base acre, a 128% increase.

- Long-grain rice payments would increase from $110 to $290 per base acre, a 155% increase.

Under the House Bill, commodity title payments for all program crops are projected to increase, but the proposed changes to the program designs, especially increases in statutory reference prices, disproportionately increase payments for base acres of seed cotton, peanuts, and rice. Relative to the other major crops, increases are marginal for corn and soybeans when compared. Moreover, differences in expected payments would not change fundamental economic realities for corn and soybean farmers. For example, the $9 increase in expected corn payments will be helpful but likely not materially change the return outlook for a Midwest farm with a corn base. The same is not true for seed cotton, peanuts, and rice, as seed cotton payments are expected to increase by $41 per base acre, peanuts by $151 per base acre, and long-grain rice by $170 per base acre.

If enacted, Midwest farmers should not expect significant additional assistance from the House Ag Committee’s Bill relative to extending the 2018 Farm Bill. Moreover, larger payments would not be realized until payment in October 2026.

Ad Hoc Economic Assistance

For corn and soybeans, prices have declined from highs in 2022 but not to the low levels of 2015 to 2019. A critical difference, however, is that the price levels projected for 2024 present issues because of much higher costs, resulting in negative farm income projections. The form of ad hoc assistance being considered is a net margin payment, with net margin equaling the difference between estimated costs per acre and revenue per acre.

Concerns about projected low farm incomes are understandable as 2024 projected incomes are very low and negative, causing many farms to experience liquidity declines, net worth reductions, and increases in debt-to-asset ratios. Whether the situation warrants additional assistance payments may depend on expectations for prices and costs, as well as the design of any assistance. Notably, many farms have solid financial positions after good to excellent farm incomes from 2020 to 2022, but some farms could face extreme financial stress as early as the end of 2024.

Adding ad hoc net margin payments to the current situation presents issues. The agricultural sector needs to see downward movements in costs to adjust to the realities of low prices. Depending on how it is designed and the amount, ad hoc disaster assistance could forestall those adjustments. Input companies, for example, will see less need to adjust their prices downward if the Federal government provides a large level of assistance. Similarly, landowners will see less need to lower cash rents because Federal assistance is being provided to farmers.

The lack of downward cost adjustments could then carry into 2025 and beyond. Projections are for continuing low prices into 2025. If costs do not decline, low and negative net incomes could continue into 2025, likely prompting interest in another ad hoc disaster program in 2025. It is reasonable to expect ad hoc aid in 2024 could lead to continuing need in 2025 and beyond.

Of course, ad hoc disaster assistance program payments are Federal outlays that also contribute to deficit spending. While agriculture is not the major contributor to Federal deficits, the issues related to deficit spending will likely need to be dealt with in the future. Moreover, some will have philosophical issues associated with Federal programs providing funding to firms, viewing it as a bail out. Furthermore, significant efforts have been made to improve crop insurance programs to eliminate the need for ad hoc disaster assistance over the past three decades. The introduction of net margin insurance could continue the trajectory of more ad hoc programs.

Final Commentary

Since 2018, a great deal of farmer support has come from ad hoc disaster assistance programs, including:

- Market Facilitation Program (MFP) payments aided in addressing losses associated with trade disruptions.

- Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP) payments aided in dealing with demand and supply chain shocks resulting from COVID-19 control measures.

- Wildfire, Hurricane Indemnity Program (WHIP), WHIP+, and Emergency Relief Program (ERP) payments aided in dealing with natural disasters.

Ad hoc programs were instituted outside of the safety net programs offered in the Farm Bill. The need for these ad hoc programs suggests that the Farm Bill programs do not meet the safety net needs of farmers. In light of these large ad hoc programs, it may be time to rethink farm programs and do more than revamp the 2018 Farm Bill, particularly given that the House Agricultural Committee Bill provides limited additional support for Midwest agriculture.

Source : illinois.edu