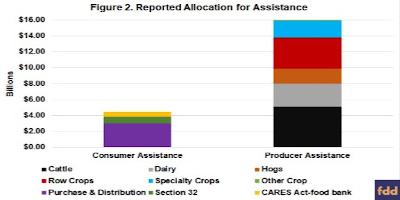

Of the 21% allocated for consumers, USDA announced that it would spend $3 billion (67%) to purchase fresh produce, dairy and meat with a procurement of $100 million per month for each category. The allocation and use of limited funds and resources raises questions about priorities in this particular crisis.

Discussion: Purchases or Payments, A Question for Priorities

In a crisis, providing relief is undoubtedly important and critical. Policy decisions and use of funds are statements of priorities. The questions raised by the latest USDA announcement is not a doubt or discount of the damage done to the agricultural and food sectors but of priorities. Specifically, does the current crisis call for more payments or for more efforts toward purchases and direct relief to consumers that can ripple throughout the supply chain.

(1) Row Crop Payments

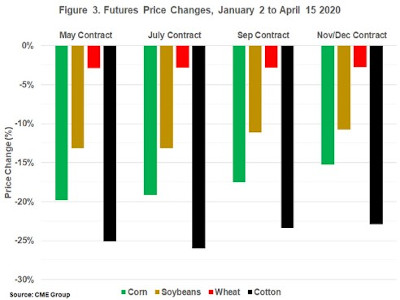

USDA has not yet officially announced how payments will be calculated but it has been reported that at least a 5% price decrease between January and April will be required to qualify for the single payment which will be calculated based on 85% of the January 1st to April 15th price loss and 30% of the expected losses from April 15th through the fall (Hagstrom, April 20, 2020).

Without further details from USDA, initial analysis begins with the changes in futures prices for four of the main commodities (corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton) for four different futures contracts, illustrated in Figure 3. Note that the use of futures prices as measures of relative (percentage) changes in prices is consistent with the forecasting model for season average prices for these commodities used by the Economic Research Service (ERS) at USDA. For corn, soybeans, and cotton the May and July contracts are relevant for “old crop” or 2019 production while the September and November (beans and cotton) and December (corn) contracts would be relevant for “new crop” or 2020 production. The old crop contracts suggest price losses of 19-20% for corn, around 13% for soybeans, and 25% for cotton. New crop contracts imply price losses of 15-17% for corn, 11% for soybeans, and around 23% for cotton. Notably, price losses for wheat average around 3% and would not be eligible for payments under this program if the announced 5% requirement is applied.

For the sake of discussion, one way for USDA to make payments to row crops and stay within the reported $3.9 billion funding allocation would be to direct payments towards existing inventories, old crop yet to be sold; this would focus support to existing inventories most likely realizing losses due to COVID-19 price shocks largely unavoidable by producers.

Figure 4 shows the most recent 5-year rolling average monthly marketing weights for corn, soybeans, cotton (a 7-year average for cotton), and wheat. These are the marketing weights used in the ERS season average price forecasting model. From January through the end of the marketing years, farmers typically market 60% of previous year’s crop, having already sold the first third in the last 4 months of the previous calendar year.

Figures 3 and 4 combined with reported details about payment calculations would imply payments to corn producers of nearly $2.6 billion, $825 million to soybean producers, and roughly $320 million for cotton—a total of $3.7 billion and leaving just $155 million for other row crops. Importantly, these estimates are purely speculative and may not reflect the methods USDA will implement to estimate payment levels.

By any measure, potential 2019 crop loss estimates—nearly $8.75 billion—far exceed the $3.9 billion allocated to payments. And this loss estimate doesn’t fully take into consideration the potential fallout for the 2020 and future crop years. For example, the renewable fuels industry may continue to suffer indefinitely, especially if recent RFS waivers are granted (Neeley, April 16, 2020). There will be additional harm if shutdowns and slowdowns at meat processing plants impact feed demand; together these two sectors consume nearly 90% of all corn produced in this country. It raises tough questions about the best way to design and allocate payments to address the harm from this pandemic crisis, and whether this first wave is just a down payment on much more support that could be required to prevent major structural change across the sector.

(2) Purchasing Authority and Questioning Priorities

Paying producers for market losses is from the standard response playbook but the current crisis likely demands different and additional response priorities. Consider that in the last five weeks alone, more than 26 Americans have filed jobless claims and those on unemployment insurance approached 16 million by April 18th (Cohen, April 23, 2020; Dept. of Labor). Figure 5 illustrates the devastation in the workforce based on data from the Department of Labor weekly news releases.

Those Americans who lose their jobs will struggle to pay their bills, manage their families and homes which includes purchasing food produced by farmers; estimates are that poverty levels will spike and that job losses and poverty will have longer-term impacts on the food and agricultural sector (DeParle, April 16, 2020). The point is not to minimize the losses that farmers are facing nor is it to insinuate that USDA is not helping those Americans who lose jobs and income. It is also not to suggest a wider role for USDA than is feasible or permitted under law, rather the point is to raise questions about priorities. In particular, priorities based on an assistance program of which only 21% is allocated to food assistance and that provides more in payments to row crop farmers ($3.9 billion) than it will use to purchase and distribute food ($3 billion) or to help those farmers producing fresh vegetables and fruit ($2.1 billion).

The question of priorities is important because USDA has authorities to do more than make payments; capabilities more applicable in the current crisis. There are sirens blaring for urgent efforts on food needs in the pandemic—lost jobs and poverty—and for the kind of creativity USDA has used to make payments to farmers. That includes troubling examples of waste and loss such as recent reports that the U.S. may have wasted up to $5 billion in fresh fruits and vegetables (Elis, April 22, 2020). The Dairy Farmers of America estimated that between 2.7 million and 3.7 million gallons of milk could be dumped each day even as almost all food banks are trying to deal with increased demand (Camero, April 16, 2020; Kulish, April 8, 2020). At the same time, some Americans face occasional empty shelves at the grocery store (Munisamy, April 13, 2020) and there have been concerning reports of current or potential disruptions in food supply chains (farmdoc webinar, April 21, 2020; Uhler, April 13, 2020). While these losses are not something that can be blamed on USDA—nor something it can completely address—they are reminders of the need to prioritize purchases and distribution.

USDA possesses important authority to purchase foods and distribute them to meet needs, beginning with a permanent appropriation based on the equivalent of 30% of annual customs receipts to purchase commodities and donate them, known as Section 32 authority (Monke, CRS Report RL34081, October 17, 2016). USDA has reported expected increases in funding available for Section 32, as illustrated in Figure 6 (USDA 2021 Budget Explanatory Notes, Agricultural Marketing Service).

In addition to Section 32 funds, USDA also has authority under the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) Charter Act, which has been used by USDA to make MFP payments, among other creative uses (Stubbs, CRS Report R44606, September 4, 2019). Section 5(c) of the Charter Act provides authority to procure agricultural commodities (other than tobacco) to provide relief and meet domestic requirements (USDA, CCC Charter Act). The CCC line of credit is, however, capped at $30 billion and the $14 billion reimbursement in the CARES Act does not appear to apply to the account until July; every dollar spent from the CCC limits USDA’s ability to purchase and distribute food in the depths of this crisis (farmdoc daily, April 2, 2020).

Finally, and likely as a last resort, under the Defense Production Act, USDA has been delegated authorities for prioritizing and allocating food resources. Congress enacted the Defense Production Act (DPA; P.L. 81-774) in 1950 in response to the potential needs of the federal government during the Korean War (Brown and Else 2014). The authority is used to give instructions to private industry to produce and provide essential materials, goods and other items to help meet national defense needs and now includes domestic emergencies. These authorities have been further delegated to the Farm Service Agency (FSA) in the Agriculture priorities and Allocation System (APAS; 7 C.F.R. §789 et seq.); FSA also administers the CCC, distributes payments and provides loans to farmers. If needed, the DPA and APAS provide authority for USDA to prioritize and allocate food to communities and areas that need it most; on its own or in combination with Section 32 or CCC authorities.

How might USDA get creative with its authorities? Anecdotal reports provide both inspiration and opportunity: some schools have transformed into relief response kitchens to help not only children but also struggling adults; the latter assistance might not be reimbursed, however (Green and Fadulu, April 19, 2020). Consider that there are over thirteen thousand public school districts and nearly 99,000 public schools in the U.S. (NCES). Moreover, according to the School Nutrition Association, the National School Lunch Program includes nearly 100,000 schools or institutions that served lunches to 29.8 million students each day in normal times; 4.9 billion lunches are served each year (School Nutrition Association). These currently idle facilities throughout urban, suburban and rural America hold real potential for helping distribute food; an opportunity for creativity in a pandemic that should be a priority at USDA. Together they serve as a reminder of the massive machinery that could be mobilized to move food from fields to tables helping to avoid waste, losses and hunger in this time of crisis.

Concluding Thoughts

The bottom line is one of priorities. USDA has substantial authority for taking creative actions to provide assistance to farmers and American consumers, as well as multiple sources of funding that can be used—but neither is unlimited. To date, USDA has proven incredibly creative in the use of authorities to pay farmers. Given the scale and scope of this situation and its impact on people and families trying to feed themselves amidst lost jobs and sickness, USDA should arguably show an equivalent amount of creativity to help the broader spectrum of struggling Americans with food needs. Funding is limited, so are employees and facilities. The questions raised by the most recent USDA announcement highlight the issue of whether to prioritize purchases and distribution or payments. Farmers are hurting but so is a vastly larger population of Americans who are also consumers of all the hard work that happens on farms. This time of pandemic and economic crisis cries out for setting aside business-as-usual to focus funding, authorities, facilities, time and resources where the needs are the greatest and most pressing; time is of the essence.

Source : illinois.edu