NASA Harvest, established in 2017, is the agriculture program of NASA Applied Sciences.

Sarah Brennan, deputy program manager of water resources and agriculture at NASA and Mary Mitkish, assistant program manager at NASA Harvest, each admit that many people are surprised that NASA focuses on work on earth, let alone has an agricultural focus.

Brennan said that when people find out what she does, “I get at least one person that says, Oh, cool. You’re looking for water on Mars.”

But for Brennan, Mitkish and many others at NASA and NASA Harvest, their focus is considerably more terrestrial than extra.

The idea for an agricultural arm of NASA started swirling around the mid-1970s after the “Great Grain Robbery,” in which in the wake of drought and crop failure, the Soviet Union purchased 10 million short tons of grain, particularly wheat and corn, from the United States at subsidized prices. It caused prices to skyrocket.

American negotiators didn’t realize that global stocks were low, losing significant revenue by subsidizing the grain rather than selling it at market price.

Global food prices rose at least 30% and grain stockpiles were decimated.

Just a few weeks after the trade, the satellite Landsat 1 was launched. Had it been launched just a few months earlier, American negotiators may have realized the global shortage and never agreed to the deal.

That was kind of a red flag that the U.S. needed to keep track of what was going on in agriculture, which is a major industry, Mikish said.

Fortunately, NASA is rich with useful satellite data and information that can paint a pretty clear picture of what’s going on globally, she added.

But there’s no point in creating some wonderful, highly technological, robust tool that no one has access to, Mikish pointed out.

“That’s why our program was established,” she said.

Mikish said the goal of the program is to take all the technology and data information and bring it back to end users, the farmers.

One area of focus is water management.

Satellites up to 400 miles in space can determine soil moisture on Earth, as well as inform us about water availability and streams by monitoring dust in the mountains.

Ultimately, this information can help farmers make decisions about irrigation needs, particularly in mountain states that rely on snowmelt.

Historically, water managers would estimate when snow would melt and therefore how much water is in the rivers by using models based on temperatures. However, satellite imagery can get more accurate data by monitoring dust on the mountains.

“By monitoring from space how much sunlight is being absorbed by the snow and mountains, we can improve snowmelt estimates by one to three weeks,” Brennan said.

NASA Harvest also partners with non-governmental and humanitarian organizations, independent farmers and farmers organizations, including Farmers Business Network (FBN), to build their data and train their models. The two spoke at FBN’s Farmer2Farmer conference in Omaha last month.

Listening to what farmers want and need from this data is key, Mikish said.

They want to know what information is missing in farmers’ systems, how NASA Harvest can provide that information to farmers, how they can integrate it, and how they can improve the tools that farmers are already using.

“It doesn’t make sense to go back and reinvent the wheel and start over. We need to meet you where you’re at,” Mitkish told the room packed with farmers from around the U.S. and Canada.

A significant benefit of NASA Harvest’s data is that after a major event, they are able to get data significantly sooner than any other organization.

Mitkish hearkened back to the derecho that hit much of the upper Midwest, particularly Iowa, in 2020. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the storm was the costliest thunderstorm in U.S. history.

“We feel it’s really, really important to have the frameworks in place when severe weather events happen to be able to get a quick, accurate picture of damage to fields,” Mikish said.

Having these systems and research in place when something happens enables them to quickly take any necessary action.

This could even lead to quicker insurance payouts, she said.

In fact, as NASA Harvest looks to continue to partner with outside organizations, crop insurance companies may be a good fit.

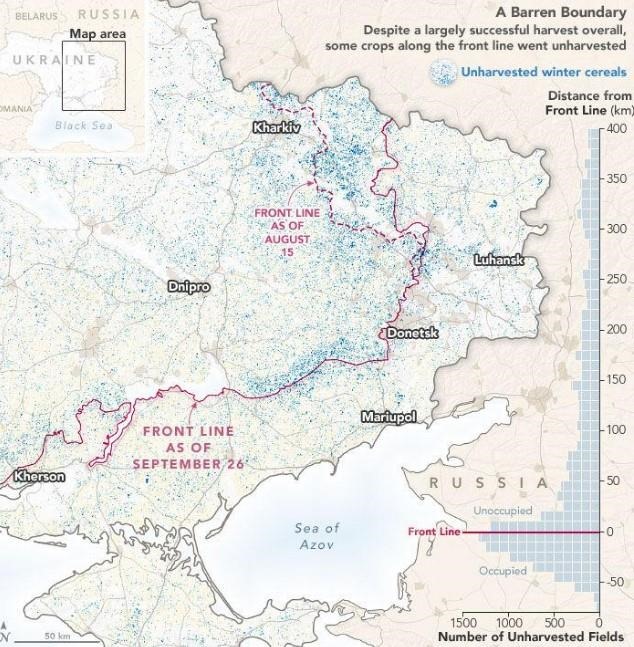

It’s already underway in Ukraine.

NASA Harvest has partnered with Swiss Re, a reinsurance company based in Zurich. NASA Harvest uses remote sensing to access damage and get checks into the hands of farms more quickly.

Click here to see more...