By Beth Ferry

Why pig aggression?

Despite undergoing genetic selection for commercial production, free-ranging (feral) pig populations adopt similar behavior to their wild boar ancestors, living in social groups of two to six females along with their litters, and sub-adults [1]. These groups form linear dominance hierarchies, based on age and size, with one “boss sow” and the remaining individuals in order below. This hierarchy is established and maintained without or with very little aggression.

Boars are generally solitary, or live in bachelor groups, coming into contact with females only for breeding, and when they do, they take top spot in the dominance hierarchy. Wild populations inhabit home ranges, which can overlap between groups, but rarely result in between-group aggression, as pigs generally adopt an avoidance strategy rather than overt aggression [2].

On commercial farms, nursery to finisher pigs are kept in various social groups sizes of up to hundreds or even thousands of pigs. Breeding gilts and sows are housed individually or in groups that can reach hundreds, and breeding boars are housed individually. Due to the inherent need to establish a dominance order, re-grouped unfamiliar pigs in a commercial setting engage in aggressive interactions. Due to the nature of pig production systems, pigs may have to be re-grouped at various stages, for example, entering the nursery stage, the feeder/finisher stage, at transport and/or immediately before slaughter. Vigorous fighting associated with re-grouping events, cause injury [3], stress [4], altered immune function [5], and reduced average daily gain [6]. This means re-grouping events can be associated with a reduction in productivity and animal well-being.

Michigan State University (MSU) research project

By April 1, 2020, Michigan pork producers will no longer be able to house sows in individual gestation stalls from the point at which pregnancy is confirmed. Group-sow housing will enable sows to move around, engage in positive social interactions, and choose where to lie to improve thermoregulation.

However, as breeding sows have, on average, three to six litters during their reproductive life on the farm, this will involve several re-grouping events, and numerous potentially aggressive encounters. As such, pork producers have concerns regarding sow well-being and productivity in group systems due to injuries and lameness from aggression. Michigan is one of 10 states to put this regulation in place and several pork retailers are also requesting pork be from pigs raised in this manner. Several other countries globally have also made this transition recently or are embarking on the change in the next few years. Therefore, this is an issue of national and global importance. At MSU, a team of researchers are working on advancing the knowledge related to the genetics and behavior of pig aggression, to further investigate the possibility, including potential side-effects, of breeding a less aggressive pig.

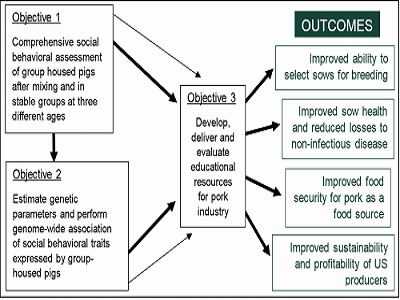

The overall aim of the project is to reduce production losses using behavioral and genomic tools to identify pigs best suited to group living (see below).

- The on-farm data collection phase of the project is now complete, including detailed behavioral data (phenotypes) for 1079 gilts and barrows. Individual pigs have been followed from birth, through re-grouping on entry to the nursery phase, feeder/finisher phase, and replacement gilts entering the breeding herd (Obj. 1). Researchers are currently studying the data to characterize the level of aggression at the different stages, as well as individual consistency of aggression.

- The researchers also obtained genotypes for these pigs, to conduct genome wide association studies (GWAS), associating variation in the aggressive phenotype of the pig, with regions on the genome (Obj. 2). This provides the potential for geneticists to incorporate selection against these ‘aggressive’ genes, without spending hours recording aggressive behavior of individual pigs, and ultimately create a pig better suited to group living.

- A third component to this project is to consider behavior in the development of on-farm management protocols to reduce production losses, by surveying pork producers, and pork industry advisers (researchers, extension educators, swine veterinarians). Survey results are being used to develop educational resources for pork industry stakeholders, including methods to better transfer and incorporate research results into on-farm management (Obj. 3).