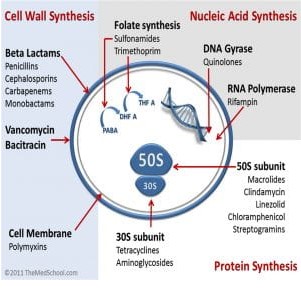

Why do some calves respond to metaphylaxis while others have to be pulled and treated again? It is easy to see why successful treatment of bronchopneumonia is not simply a matter of grabbing a bottle of the latest and greatest antibiotic, shooting it in the sick calf and waiting for the magic bullet to take effect. Instead, full recovery is a joint effort between the calf’s immune system and the selected drug to stop the growth of bacteria and destruction of lung tissue. Antibiotics are designed to hold the bacteria “in check” and give the calf’s immune system time to gear up and effectively fight the disease. Treatment failure may be due to calf factors including overwhelming stress, concurrent infection with BVD, or nutrition-related factors such as trace mineral deficiencies or subacute ruminal acidosis. Sound nutrition and management, especially around weaning, will substantially increase the response to antibiotics. Calves vaccinated 2-3 weeks pre-weaning against respiratory viruses are known to respond faster and better to antibiotic therapy if needed. A good environment with plenty of space, clean water and bunk space reduces stress. Quick identification and removal of PI calves is through a simple, inexpensive ear notch skin test. Trace mineral deficiencies can be addressed immediately with an injectable trace mineral while calves are transitioning to a trace mineral mix. Keeping high quality, leafy, green, palatable grass hay available is the best way to start them eating. Treatment failure due to human errors may include poor timing, use of the wrong drug, improper dose or route of administration, or mishandling the drug itself. The most common error, by far, is failure to recognize a sick calf. Timing is crucial; if calves are treated early during disease, almost any antibiotic will work. Conversely, if calves are treated late during the disease, nothing will work. In addition to timing, dosage is crucial because antibiotics work by different mechanisms. Figure 1 graphically displays the difference between antibiotics that are considered “time dependent” (effectiveness depends on exposure to the drug for a certain length of time) versus “concentration dependent” (bacteria must be exposed to a high concentration of the drug). If label directions are not followed and only a partial dose is administered or perhaps a second dose is required but not given, the drug is unlikely to work effectively because it cannot reach the necessary minimum target concentration. Selection of the best antibiotic class or “family” is an equally important success factor. Figure 2 is an illustration of the mechanisms antibiotic classes use against bacterial cells. Beta-lactams (penicillin, Excede®, Naxcel®, Excenel®) cripple production of the bacterial cell wall that protects the cell from the external environment. Aminoglycosides and Tetracyclines (LA-300®, Biomycin®, and many others) interfere with protein synthesis by shutting down the machinery in the ribosome needed to build proteins. Macrolides (Draxxin®, Micotil®, Zactran®, Zuprevo®, Tylan®) and Chloramphenicol derivatives (Nuflor®) also interfere with protein synthesis although at a different location on the ribosome. The Fluoroquinolones (Baytril®, Advocin®) block genetic replication by interfering with DNA and RNA synthesis. Why is this information important? If a calf requires retreatment, selection of an antibiotic from a different class will attack the bacteria through a different route and often improves treatment response. Another good example is treatment for Mycoplasma bovis, a bacterium frequently found in chronic pneumonia cases. It has no cell wall so treatment with a Beta-lactam (such as penicillin or Excede®) will prove absolutely useless. A veterinarian is well-trained in antibiotic selection and is the best source of information when choosing therapy. Another issue that may affect success is mishandling the

product; an antibiotic that gets too hot or freezes will inactivate the drug in most cases. Sometimes treatment failure is not a “failure” but rather an inability to recognize recovery. A calf that is eating, drinking and looks better after treatment but still has a slight fever often just needs time to fully recover since fever is one of the last clinical signs to disappear.

Figure 2: Drawing of a bacterium illustrating the ways different “classes” of antibiotics fight against them.

Strategic and correct use of antibiotics will continue to be of importance for the cattle industry from this point forward. Metaphylaxis is one method to head off a likely respiratory break, especially in highest risk calves. In addition, careful attention to timing of treatment, drug selection, dose, and handling of the product will reduce the human factors that contribute to treatment failure. Calf factors including overwhelming stress, infection with BVD, environmental or nutrition-related disorders must also be addressed in order for the calf’s immune system to work with the antibiotic to stop disease progression.

Source : osu.edu