By Romulo Lollato,John Holman.et.al

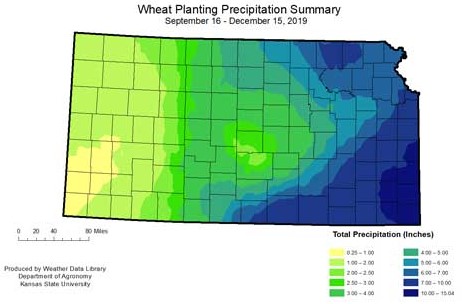

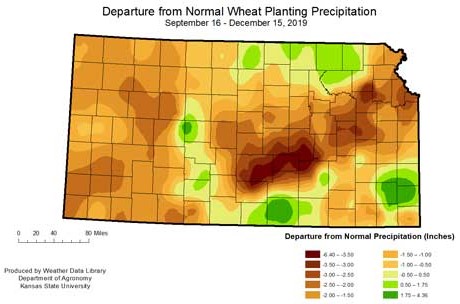

Total precipitation during the period from September 16 to December 15 for Kansas is shown in Figure 1. The far portion of southwest Kansas (Morton, Stanton, and Hamilton counties) only received 0.25 to 1 inch of precipitation during this period, and a large portion of the western third of the state only received 1 to 2 inches. Likewise, a dry spell occurred in south central portions (Reno, Rice, Stafford, and Barton counties). These values represent a negative departure from the normal (3 to 6.4 inches) for the region. Consequently, many wheat fields in these regions either had poor emergence (Figure 2) or no emergence at all. In regions that had some fall moisture, planting mid-to-late September tended to produce better fall stands than planting mid-to-late October.

Figure 1. Precipitation summary for the period from September 16 to December 15, 2019 (upper panel) and departure from normal for the specified period (lower panel). Maps from the Weather Data Library, Kansas State University.

Figure 2. Poor stand establishment in wheat trials sown near Great Bend (Barton Co) due to extremely dry fall conditions. The target wheat population ranged from about 20 to 40 plants per square foot (depending on the study) and the actual emergence ranged from 5 to 12 plants per square foot. Trials were sown in the later portion of October and pictures taken on December 12 by Kavan Mark, Assistant Scientist at K-State Wheat and Forages Extension program in the Department of Agronomy.

Actual vs. effective sowing date

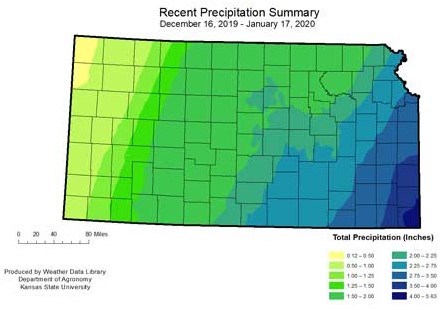

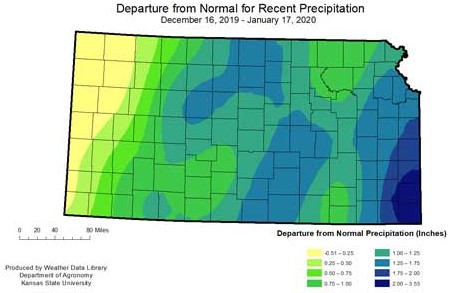

While many producers in southwest Kansas may have sown the crop on time, the effective sowing date (or the emergence date) is actually considerably later in many fields due to the dry conditions experienced during most of the fall. The recent precipitation (either as rainfall or ice, Figure 3) will benefit the crop, as the cumulative precipitation amounts would be sufficient for the crop to emerge. Studies showed that approximately 0.4 inch of precipitation should suffice for even emergence and a good stand establishment for a wheat crop sown about one inch deep or less. Thus, the precipitation received in southwest Kansas should be enough to help fields with no wheat emergence yet to make it out of the ground for as a spring-emerged crop, provided the seed is still viable. Un-germinated seed might not be viable in cases where it started to germinate and then dried out for lack of moisture, or maybe when suffered insect or disease damage, or wildlife feeding. There are some fields or areas within a field that germinated, but due to insect and dry conditions, the seedlings are no longer alive.

Figure 3. Precipitation summary for the period from December 19, 2019 to January 17, 2020 (upper panel) and departure from normal for the specified period (lower panel). Maps from the Weather Data Library, Kansas State University.

What to expect from a yield potential stand point?

It is important to keep in mind that spring-emerged winter wheat has considerably less yield potential than a fall-emerged crop. Producers will have to decide whether maintaining the crop is a viable option.

Reasons for the generally observed decreased yield potential with a delay in sowing date include:

- Less fall tillering potential: fall-formed tillers are generally more productive than spring-formed tillers. When wheat is sown late, it will have less time to tiller in the fall, which decreases the production of higher yielding tillers as well as total tiller production. Due to the dry fall conditions, many producers planted at a higher population to overcome less tillering - this will help reduce the yield loss that would have occurred.

- Delayed cycle: late sowing often delays the entire crop cycle as compared to a crop sown earlier. As a consequence, the grain-filling period might occur a few days later and under hotter air temperature conditions, which decreases yield and test weight.

- Greater exposure to winterkill: a wheat crop with 3 to 5 fall-formed tillers has greater cold tolerance than a crop that has only one or two tillers. As a consequence, late-sown fields might be more exposed to winterkill, especially in dry conditions.

Research conducted by Merle Witt with late-sown wheat in Garden City during 1985 through 1991 is summarized in Figure 4. Averaged across all these years, delaying wheat sowing from October 1 to November 1 delayed heading date by six days and decreased wheat yields 23%. Grain filling period was progressively shortened in about 1.7 days and occurred under hotter temperatures (about 1.5 degrees F) for every month of delay in sowing date.

Figure 4. Wheat grain yield, test weight, and heading date responses to sowing date between 1985 and 1991. Data adapted from Kansas Agric. Exp. St. SRL 107.

Therefore, the potential consequences of the delayed progress of the Kansas wheat crop during October include greater exposure to winterkill, delayed crop cycle for grain filling under warmer conditions, and a lower yield potential due to decreased fall tillering. Particularly in the western half of Kansas, research evaluating effects of weather conditions on long-term variety performance tests indicated that wheat yields were influenced the most by favorable precipitation conditions during the fall that promoted stand establishment and moist soil conditions (Holman et al. 2011). However, if the weather conditions during the remaining season are favorable (mild winter, and cool and moist spring), the crop might still result in a decent yield (Figure 5).

Figure 5. K-State wheat demonstration plot near Dodge City, KS, during June 2017. While this crop was sown normally during October 2016, it had not emerged in the fall due to extremely dry conditions. An ice storm on January 2017 sufficed for the crop to emerge, and favorable winter and spring weather conditions led to a decent yield potential despite harsh initial conditions.