By Eric Anderson

Irrigation of crop fields is a common practice in areas of the country that receive little rainfall or have soils with little water-holding capacity. A few regions in Michigan that have light-textured soils have seen a significant increase in irrigated acres in the last 50 years, including counties in the south central and southwest part of the state. Farmers have used different approaches in deciding when to irrigate, including assessing the look of the crop, checking soil wetness to shovel depth and, more recently, more sophisticated methods like irrigation schedulers that are based on evapotranspiration rate estimates (see “Irrigation Scheduling Tools” by Michigan State University Extension and Purdue University Extension). While these approaches can be used successfully, a more direct method for measuring how much soil moisture is available to the crop involves the use of soil moisture monitors.

Measuring accuracy and uniformity of irrigation equipment is important to ensure all areas of the field receive adequate, but not too much, water for crop growth.

Wally Hekter, a second-generation farmer with Legacy Land Farms, Inc. in Michigan’s St. Joseph County, has been experimenting with soil moisture monitors for the past three years and has seen the benefits of utilizing this technology. Although he admits using irrigation schedulers and observations of the crop and the soil surface are useful, he says the first major benefit of using moisture sensors is knowing exactly how much water he has available for the crop at any given time – what he calls “balancing the checkbook.”

“It is good to measure what is going in (irrigation and rainfall) and what is going out (evapotranspiration estimates), but it is important to balance the checkbook to make sure you have in the ‘bank’ what you think you have,” says Hekter.

The second major benefit is the peace of mind he has, knowing that he does not need to guess whether he should irrigate on any given day because he can make the decision based on actual scientific soil measurements.

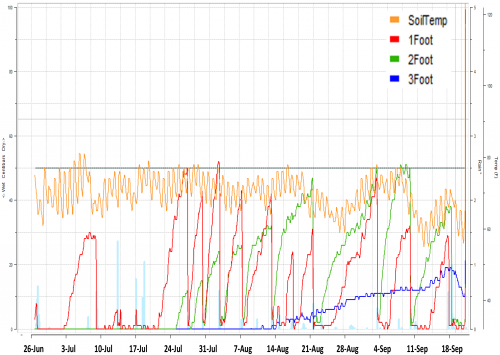

Hekter has a set of sensors in each of his fields, one each at 1-, 2- and 3-foot depths. The figure below is a season-long graph of soil moisture as measured with these sensors. The gray line at 50 centibars (cbar) was considered the wilting point for the crop in a sandy loam soil, while 0 cbar represents the maximum water-holding capacity for this field. The goal is to irrigate enough to keep soil moisture below 50 cbar, but not so much that water (and nutrients) is lost through leaching. We can see that the top 1 foot dried out the fastest early in the season and reached 50 cbar a few times in July. The soil at 2 and 3 feet began to dry out beginning in July and August, respectively, showing that the crop roots had grown downward and were extracting water from those depths.