Everyone is probably sick of me talking about the importance of winter wheat establishment and the need to seed winter wheat at the optimum time for improved success, yet we continue to push winter wheat seeding dates later and later each year. While there may be situations where we get away with seeding wheat into late October and November, it doesn’t mean it will always work. So why do we get away with planting late on some years versus others? Well, Growing Degree Days (GDDs) have a lot to do with it along with the conditions at seeding.

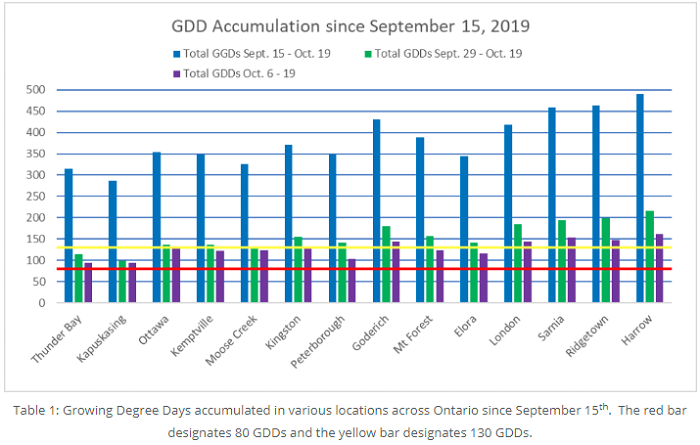

Cereal development can be determined by following GDD accumulations. GDDs can be calculated by taking the maximum and minimum daily temperature adding them together and then dividing them by 2. You then subtract the base temperature for winter wheat which is 0. The number you get is the number of GDDs accumulated for that particular 24 hour period. If the daily mean temperature is equal to or less than the base temperature (base temperature for cereals is 0), the degree-day value is zero. In order for cereals, or in this instance winter wheat, to germinate they require approximately 80 GDDs and another 50 GDDs to emerge. So in total winter wheat requires at least 130 GDDs in the fall just to emerge! While that may not seem like a lot, as we push dates further and further the less GDDs we accumulate before the crop goes dormant and the less yield potential we have.

Ontario research has shown that for every day we delay seeding beyond the optimum seeding date for a region we lose 1.1 bu/ac/day. You’re probably thinking that isn’t a big deal but what if you have to delay your seeding by 7 days? Suddenly that yield loss jumps to 7.7 bu/ac and if you delay even further to 14 days beyond your optimum seeding date that yield impact is even greater at 15.4 bu/ac.

To give you a sense of how this works, I tracked the GDDs for a number of locations across Ontario with the help of historical data from Environment Canada (Table 1). If we look at the GDD accumulations for winter wheat planted September 15th (blue bars) until October 19th, with the exception of Kapuskasing, all locations received more than 300 GDDs to allow the crop to germinate, emerge and put out some tillers in some cases before this winter. The more fall tillering that occurs not only maximizes the yield potential of the crop, but it also increases the chances of winter survival. As you continue across the bars and look at the accumulation since September 29th (green bars), you can see there has been a decline in GDD accumulation and there are still some locations that have not received enough GDDs to allow the crop to emerge. If you look even further at fields planted since October 6th (purple bars), even fewer locations have received enough GDDs to emerge.