Bridging the gap for cattle between corn residue grazing in winter and summer pasture is one of the primary objectives. This rotation provides annual forage grazing resources for the critical April-May period in the spring and for the October-November period in the fall. Of course, these forages could alternatively be mechanically harvested and fed throughout the year as needed.

Economically, the producer moving from a two-year corn-soybean rotation to the three-year rotation depicted in Figure 1 would be trading off one-third of the net returns for corn and soybeans for the net benefits of growing two forage crops in one year on a third of their acres. Most people considering this rotation live in the Corn Belt with adequate moisture to support the cropping intensity and possess a desire to improve soil physical properties by growing something other than just corn and soybeans.

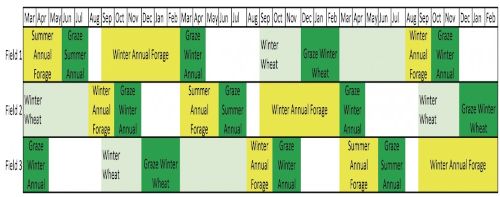

Figure 2 depicts a scenario where a typical two-year wheat-fallow rotation is expanded to a three-year crop rotation with up to three annual forages added to the winter wheat rotation.

All of the annual forages in this rotation would be considered “options,” depending upon the prevailing soil moisture conditions, as would grazing of the winter wheat crop during the dormant season.

From a livestock production standpoint, the rotation in Figure 2 potentially provides annual forage-grazing resources year-round. The two grazing gaps that occur in May and the two-month period of August through September could be closed by extending the grazing season of winter-hardy annual forages into May and by using a mix of cool-season and warm-season forages to extend the June-July grazing season into August and September.

In the rotation depicted in Figure 2, each acre would produce a winter wheat crop and one to three annual forage crops every three years. Economically, the producer moving from a two-year wheat-fallow rotation to the three-year rotation depicted in Figure 2 would be trading off one-third of the net returns of growing wheat for the net benefits of growing one to three annual forage crops.

Of course, the intensification of the crop rotation could have a negative impact on wheat yields in low-moisture conditions. However, the rotation is designed to provide flexibility for the producer to adjust the manner in which annual forages are utilized in a given year to match production conditions and, hopefully, mitigate the risk of negatively impacting wheat yields.

Each of the rotations in Figures 1 and 2 provide flexibility for the crop producer to quickly adjust back to the original rotation if market and/or production conditions warrant the change.

Insurance for annual forages

Soil moisture and precipitation present some of the biggest risks when planting annual forages, especially in dryland production situations. The Annual Forage Insurance Plan (AFIP) from the USDA Risk Management Agency (RMA) is a tool that may help mitigate this risk. However, it is currently only available in Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Texas. AFIP insures annual forages, planted for use as livestock feed or fodder, against low precipitation based on precipitation index data provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – Climate Prediction Center.

The annual signup deadline is July 15, with coverage available for four different planting periods that include the entire year. More details on AFIP coverage are available at the RMA website or from a local crop insurance agent.

Source : unl.edu