The big picture when it comes to flock management is ensuring that you are meeting the flock’s nutrient requirements in every stage of production. With forage being limited, it is especially important to match ewe nutrient requirements with available forage. Producers fall lambing will need to take greater consideration, as requirements climb in late gestation coinciding with rapid declines of forage quality or potentially no grazeable forage. Even though drought-stressed plants can delay maturity and going to seed, overall forage quality will likely be lower. An earlier plant dormancy cycle should be expected, with a need for ewe supplementation prior to the normal dates.

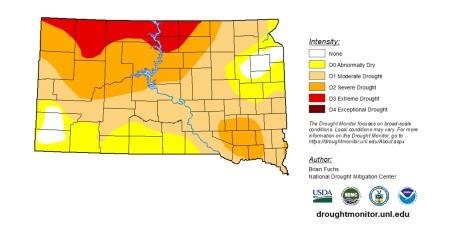

Figure 1. U.S. Drought Monitor for South Dakota. Released Thursday, June 3, 2021. Courtesy: U.S. Drought Monitor

As lower forage production is expected with drought, stocking rates should be adjusted to reflect available grazing forage. Areas across South Dakota are showing to have only received 70% of normal precipitation according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, and thus only having 70% or normal forage production in pastures. In these situations, it should be expected to cull up to 30% of the flock to ensure adequate grazing is available for remaining livestock. Making critical decisions, like culling livestock early, is essential for an operation to make it through a drought. Reluctancy often comes with higher culling rates, but current sheep prices might make that decision a little easier. Culling criteria should reflect your production goals, such as increasing number of lambs weaned by culling ewes that fail to raise lambs to weaning or mastitic ewes. Future mastitis problems can be reduced by bagging ewes at weaning and culling ewes with hard knots in their udder. Body condition score (BCS) can also be used as a culling tool. Consider culling ewes in low (2 or lower) BCS, since increasing BCS requires greater feed resources, which will be further challenged by a drought year. Retaining fewer ewe lambs may be an option as well given the climbing feed prices and limited forage. If they are entering the production cycle to lamb around 12 months-of-age, additional feed resources are needed for successful conception.

Another management decision that should be considered during times of drought with low available forage quantities is early weaning. Early weaning can help take stress off of ewes to produce and lower feed intake needs. Early weaning can be successful as early as 60 days, and it is recommended that lambs are at least 45–50 pounds (lb.). The dry matter intake of a 154-lb. ewe raising twins in late lactation is 1.8 lbs. greater than an ewe in maintenance (NRC, 2007). Weaning those lambs a month earlier saves about 54 lbs. of feed. With 100 head of ewes, that is 2.7 tons of hay saved that can be stockpiled for later use. Lambs must be established on a creep feed prior to weaning. Younger, weaned animals have a greater average daily gain, so setting a target sale weight can be achieved quicker than if they were still on the ewe. Currently, there is a market for 45–50 lb. lambs, so they can be sold without being fed on creep. However, retaining ownership and selling heavier-weight lambs may offset the feed costs and increases the profitability per lamb. A partial budget is a helpful tool for assessing relative profitability of making a management change, such as early weaning.

Additionally, monitor for diseases that can be exacerbated in drought years. Warm, dusty conditions may increase the appearance of pneumonia and pinkeye. Worm burdens can also worsen if animals are grazing forage two-to-three inches from the ground. Selective deworming of animals that have high worm burdens rather than mass deworming can fight against dewormer resistance and cut costs. Worm burdens can be assessed through Faffa Malan Chart (FAMACHA) scoring or fecal egg counts. Furthermore, populations of flying insects, like mosquitos and midges, increase in drought years. Bluetongue is a hemorrhagic virus spread through biting midges and is apparent in west-river deer populations. Sheep often appear lethargic and can have blue discoloration and swelling in the face and above the hooves. Mitigating midges is the best way to prevent blue tongue. Though often difficult on a drought year, reduce the time sheep spend around standing water, where there may be high populations of biting midges. Insecticides are also an option. Some permethrin pour-ons cover midges, though protection may not be long-lasting. Insecticide tags are effective, but cost must be considered. If blue tongue is a concern, consult a veterinarian for the best course of action.

In conclusion, having a drought plan in place to best manage pastures and the livestock that rely on them is critical in being prepared for next year’s grazing season. Avoid overgrazing for greater future forage productivity and erosion control. Continually meet requirements of the flock, even if that means finding alternative feeding strategies. Finally, make decisions that will manage risk and promote both flock and financial longevity.

Source : sdstate.edu