Preventative health care starts with the newborn calf. There are vaccination protocols for two of the most common issues affecting calf health: scours and pneumonia. There have been numerous research papers showing how coccidiosis, if not managed, can hinder animal growth. Acute and chronic insults of pneumonia can scar lung tissue, which can affect a heifer’s longevity in the herd. The short-term solution is to treat the animal so they can recover. The problem that happens is not solving the underlining issue and treatments become both the short- and long-term answer. Working proactively with the herd veterinarian and other consultants on addressing ventilation, housing, overcrowding, and nutrition will result in healthier animals that reach breeding age at 12-14 months and calve at 22 to 24 months of age.

Metabolic troubles at calving are another key area in the dairy animal’s life cycle that can have devastating repercussions if not managed. There will be those occasions when ketosis, DAs, milk fever, or retained placentas may occur but they should be the exception and not the normal. The direct costs to treat these conditions will have minimal impact on the cost of production. It will be the lost income from cows not starting off well in the first 40 days in milk and the loss in peak milk. The worst-case scenario is culling the animal and the potential loss of investment. Focusing on preventative health care versus treatment will have the greatest positive effect on animal performance and income.

The benefit of developing a cash flow plan is to look at the big picture and put income and expenses in perspective. There is a lingering mind set of making decisions on unit costs, which can be misleading and steer the farm down the wrong path. Focusing on preventative health care may result in spending more cash on service, e.g., biweekly herd vet visits and consultation versus treating an animal multiple times over an extended period resulting in lost income. For a herd milking 74 cows, an annual expense for vet and medicine can range between $10,000 to $11,000. It is helpful if this category does not include purchases for reproductive synchronization products. Those can easily inflate this line item. Detailing purchases used for treatments, vaccinations, and service can help a farm drill down to where bottlenecks may be occurring. Shifting expenses away from treatments to preventative care may not change the total expenditure, however, because animals are healthier, they are generating more milk income. Good decisions are made when both income and expenses are evaluated together.

Economic perspective:

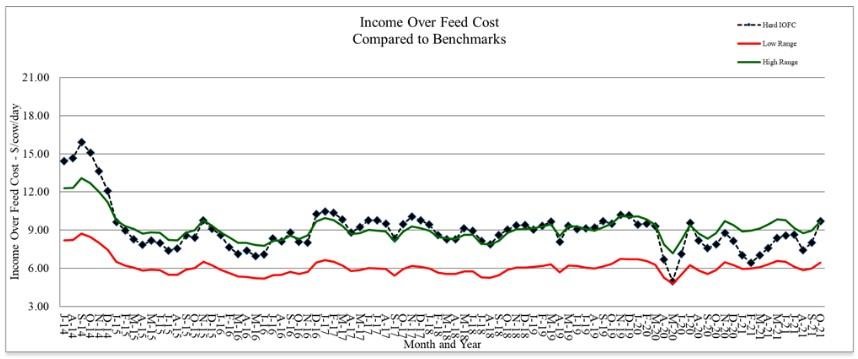

Monitoring must include an economic component to determine if a management strategy is working or not. For the lactating cows, income over feed cost is a good way to check that feed costs are in line for the level of milk production. Starting with July 2014’s milk price, income over feed cost was calculated using average intake and production for the last six years from the Penn State dairy herd. The ration contained 63% forage consisting of corn silage, haylage, and hay. The concentrate portion included corn grain, candy meal, sugar, canola meal, roasted soybeans, Optigen, and a mineral vitamin mix. All market prices were used.

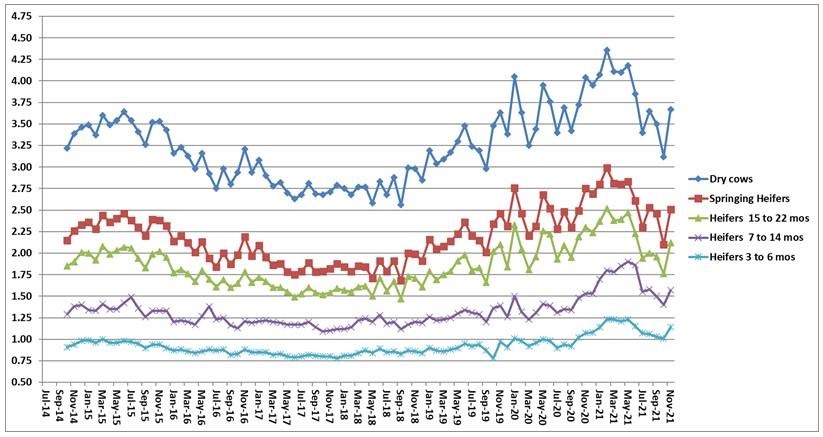

Also included are the feed costs for dry cows, springing heifers, pregnant heifers, and growing heifers. The rations reflect what has been fed to these animal groups at the Penn State dairy herd. All market prices were used.

Income over feed cost using standardized rations and production data from the Penn State dairy herd.

Note: October’s Penn State milk price: $19.90/cwt; feed cost/cow: $6.42; average milk production: 81 lbs.

Feed cost/non-lactating animal/day.

Source : psu.edu