The 2016-2020 plateau in cash rents is displayed in all I-states in the heart of the Corn Belt:

- Iowa’s cash rents declined from a high of $260 per acre in 2014 to $235 per acre in 2016. The 2020 average state rent is $230 per acre.

- Indiana’s cash rents declined from a high of $197 per acre in 2014 to $192 per acre in 2016. The 2020 average state rent was $194 per acre.

2016-2020 Plateau Corresponds to Lower Corn and Soybean Prices

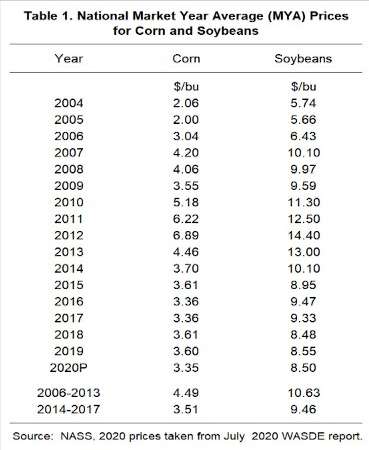

The 2016-2020 plateau corresponds to a period of lower corn and soybean prices that began in 2014. From 2006 to 2013, national average corn prices averaged $4.49 per bushel and soybean prices averaged $10.63 per bushel (see Table 1), higher than the years leading up to 2006. Expansion in corn use played a large role in price increases throughout the 2006 to 2013 period (farmdoc daily, June 10, 2020).

From 2014 to 2017, corn prices have averaged $3.51, down by $0.98 from the 2006-2013 average. Soybean prices averaged $9.46 from 2014-2017, down by $1.17 from the 2006-2013 average. These lower prices began as corn use in ethanol reached a plateau in 2012, resulting in slowing increase in corn demand.

Ad Hoc Federal Aid Supports Farm Revenue and Cash Rents in Recent Years

Since 2018, corn and soybean prices fell from 2014-2017 levels, first because of issues related to trade conflicts, with soybean prices being particularly hard hit. From the $9.46 average for 2014-2017, soybean prices fell to $8.48 per bushel in 2018, and continued at a low price of $8.55 per bushel in 2019. At the beginning of 2020, progress on the trade front brought optimism to the outlook until coronavirus and COVID-19 control measures introduced new turmoil into the economy and lowered expected prices. For 2020, MYA projections are $3.35 per bushel for corn and $8.50 per bushel for soybeans. Low prices are expected to continue into 2021 as the impact of COVID-19 control measures likely will have a long tail.

Additional Federal aid in the form of Market Facilitation Program (MFP) and Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP) payments has supported crop returns since 2018. MFP and CFAP programs are ad hoc payments because these payments are outside the usual farm safety net (i.e., Commodity title programs and crop insurance) and because the levels of payments are not legislated to continue in the future. At this time, there is no legislation or USDA announcement for additional ad hoc aid in 2020. Nor is there any assurance of continuing aid in 2021.

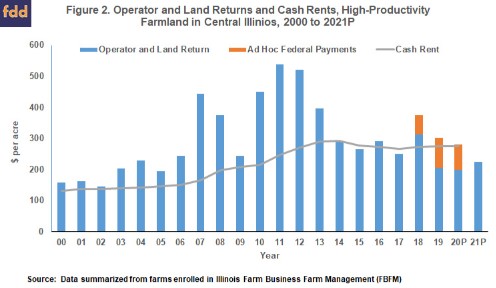

These ad hoc payments have been important sources of revenue for the 2018, 2019, and likely the 2020 crop, as is illustrated in Figure 2. Figure 2 shows operator and land returns for a 50% corn and 50% soybean rotation on high-productivity farmland in central Illinois for the years from 2000 to 2021P. Operator and land return represents a return to the farmer and landowner. If the farmer owns farmland, all of the operator and land return will accrue to the farmer, from which owned land costs such as interest on farmland debt and property taxes must be paid. Under a cash rent situation, the farmer will pay cash rent out of the operator and land return amount, retaining the difference between the operator and land return and the cash rent.

Operator and land return bars in Figure 2 include a division showing ad hoc payments in 2018, 2019, and projected for 2020. On a 50-50 corn-soybean rotation, ad hoc payments totaled $62 per acre in 2018 and $98 per acre in 2019. The $98 payment in 2019 includes CFAP payments made in 2020. The 2020 bar includes $80 per acre. These 2020 payments have not been announced or passed through Congress. We did not include any ad hoc payments for 2021.

The average cash rent for high-productivity farmland in central Illinois was $275 per acre in 2019. Although USDA did not yet release county-level cash rents for 2020, a continuation of $275 per acre for high-productivity farmland in central Illinois is likely for 2020 given no change in state cash rents as published by NASS last week.

Without ad hoc Federal payments, operator and land returns would have been lower than average cash rents in 2019 and 2020, equating to negative returns on cash rented farmland. In 2019, operator and land return was $303 per acre, with ad hoc Federal aid contributing $98 per acre to that return. Without ad hoc aid in 2019, operator and land return would have been $205 per acre, and farmers on cash rental farmland would have lost $70 per acre ($205 operator and land return – $275 cash rent). In 2020, operator and land return is projected at $280 per acre, with $80 coming from ad hoc disaster payments. Without ad hoc Federal aid, the 2020 farmer return would be projected at -$75 per acre. With Federal aid, farmer return is projected at $5 per acre.

Ad hoc Federal aid programs have been critical in keeping farmers from having losses in the past several years. Without this aid, there would be much greater pressures placed on cash rents to move downwards.

2021 Cash Rents

Budgets for 2021 have been released and are available on farmdoc (see farmdoc daily, August 4, 2020). For 2021, operator and land returns for a 50% corn 50% soybeans rotation is projected at $224 per acre based on several key assumptions:

- Commodity title payments total $30 per acre. This $30 per acre includes roughly $60 per acre of Price Loss Coverage (PLC) payments on base acres in corn. No payments are included on soybean base acres.

- 2021 prices are $3.40 per bushel for corn and $8.50 for soybeans, representing an economic recovery that is V-shaped.

- 2021 yields are at trend levels of 217 bushels per acre for corn and 68 bushels per acre for soybeans.

- 2021 non-land costs are $568 per acre for corn and $360 per acre for soybeans

- There are no ad hoc Federal payments.

One can argue with a number of those assumptions, particularly related to ad hoc Federal payments. It seems premature to estimate 2021 levels for federal aid, particularly given that a national election is scheduled for this November.

Those assumptions result in an operator and land return of $224 per acre. At our projections, a continuation of a $275 per acre cash rental rate in 2021 would result in a loss to the farmer of $51 per acre. Obviously, without reductions in cash rents or other costs, $51 per acre or more of ad hoc aid is needed to get farmers to break-even returns near $0 per acre.

When setting 2021 cash rents, two factors are important:

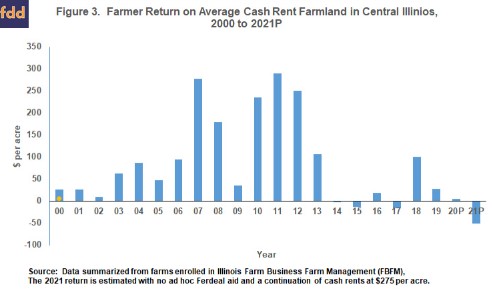

Farmer returns have been low since 2014: Farmer returns in central Illinois on high-productivity farmland have averaged $17 per acre from 2013 to 2018 (see Figure 3). From a return standpoint, $17 per acre is a low return for engaging in the risk of farming a cash rent acre. A number of reasons can be given for largely stable cash rents in recent years including competitiveness within the farmland market, farmers’ fears of loss of competitiveness if rental acres are lost, build-up of financial reserves during the high return years from 2006 to 2013, and optimism about prices in the future.

In regards to prices, there have been some points at which optimism seemed warranted. Expectations of prices near $4.00 for corn and $10 for soybeans seemed reasonable in 2018 before the trade conflicts began. Similarly, there was some optimism for improved prices at the beginning of 2020. Now, however, that optimism does not seem warranted for the foreseeable future. COVID-19 likely will have long-ranging downward impacts on prices. Trade concerns also likely contribute to downward expectations for prices. Over the next five years, it seems reasonable to expected corn prices to average closer to $3.50 per bushel than $4.00, and for soybean prices to average closer to $8.60 per bushel than over $9.00 per bushel.

Without ad hoc Federal aid, an average cash price of $3.50 per bushel for corn and $8.60 per bushel for soybeans would place operator and land return at an average of $240 per acre. This would suggest that cash rents would have to average near $240 per acre for farmers to have a return near $0 per acre, or that cash rents would have to fall $35 per acre for farmers to operate at a break-even level. In percentage terms, this decline would be 12.5%. Of course, this $35 per acre cost reduction could also come from non-land costs. Still, a $35 decline only returns to break-even levels. Larger cuts are needed for profitability to return.

Ad Hoc Federal Aid is Key to Profits: Without ad hoc Federal aid, farmer returns would have been negative in 2019 and 2020, and likely will be negative in 2021. One can speculate whether or not this aid will be forthcoming. Given this uncertainty, setting cash rents for 2020 will be difficult. Continuing setting cash rents at current levels will result in large losses if ad hoc Federal payments do not occur.

Summary

Ad hoc Federal aid has been an important source of revenue since 2018. Without these payments, cash rents or non-land costs would have to decline by $35 per acre, or 12.5%, to have farmer return to be near $0. While breakeven levels are an improvement over losses, larger declines than $35 per acre would be needed to reach a sustainable level of income for a farmer to continue operations. In anticipation of both continuing lower prices and reductions in ad hoc Federal aid in 2021, it appears time to lower cash rent levels that are average-level or higher.

Source : illinois.edu