This model is meant to be representative of an “average” plant constructed in 2007 to process soybean oil into biodiesel. There is certainly substantial variation in capacity, production efficiency, and feedstock across the industry and this should be kept in mind when viewing profit estimates from the model. However, limiting the feedstock to soybean oil is reasonable since it represents about half of the feedstock used to produce biodiesel in the U.S. and feedstock prices tend to be highly correlated.

In previous versions of the representative biodiesel plant model, a conversion factor of 7.55 pounds of soybean oil per gallon of biodiesel was assumed. Data on biodiesel production and feedstock use from the EIA’s Monthly Biodiesel Production Report were examined to determine whether biodiesel production efficiency has improved in recent years. Across all types of production feedstock (e.g., soybean oil, canola oil, animal fats) the average conversion rate was 7.50 over January 2017 through November 2020, slightly below the 7.55 conversion factor assumed in the original version of the model. The conversion efficiency did improve over this period, averaging 7.57 in 2017 compared to 7.51 in 2020. Based on this analysis of EIA data, the feedstock conversion rate in the model is dropped from 7.55 to 7.50 pounds starting in 2018.

In previous versions of the representative biodiesel plant model, it was assumed that 0.71 pounds of methanol were used per gallon biodiesel produced. The actual alcohol use per gallon reported by the EIA has been higher and increasing over time, rising from 0.77 pounds in 2017 to 0.83 pounds in 2020. Consequently, the methanol usage per pound of biodiesel production is increased for recent years. It is increased to 0.75 pounds in 2017, 0.80 pounds in 2018, and 0.84 pounds in 2019 through 2020. While the representative biodiesel plant has had some modest gains in feedstock efficiency in recent years, this has come at the cost of added methanol expenses.

To track plant profitability over time, weekly biodiesel and soybean oil prices at Iowa plants from the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) were collected starting in 2007. Natural gas costs over 2007 through March 2014 are based on monthly industrial prices for Iowa available from the EIA. Due to a change in the behavior of the industrial price series, starting in April 2014 natural gas costs are based on monthly electric power consumer prices for Iowa, also from the EIA. Glycerin and methanol prices were obtained from OPIS.

Analysis

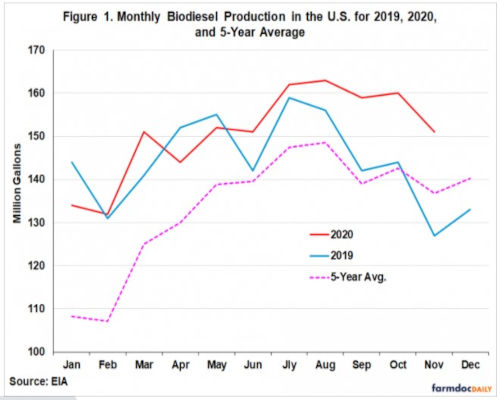

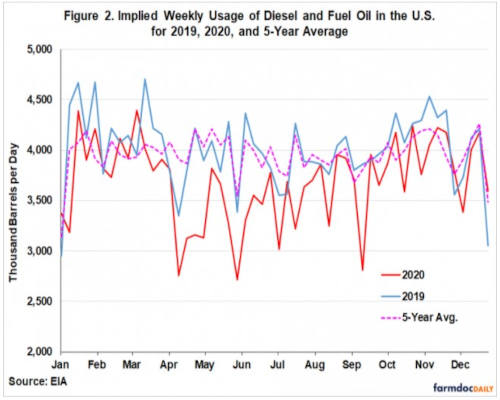

Before discussing estimates of the profitability of biodiesel production in 2020, it is useful to review the possible impact of the COVID pandemic on biodiesel production in the U.S. Figure 1 shows monthly biodiesel production in the U.S. for 2019, 2020 and the five-year average. There is a dip in April 2020 that coincides with pandemic lockdowns, but this was only a decline of 5.3 percent compared to April 2019. Thereafter, biodiesel production recovered and was actually above 2019 levels for the remainder of the year. This stands in sharp contrast to the experience of the U.S. ethanol industry, where production fell by nearly half at the peak of the pandemic lockdowns last spring (farmdoc daily, January 27, 2021). Part of the answer as to why biodiesel production fared better than ethanol production is found in Figure 2, which shows the implied weekly usage of diesel and fuel oil in the U.S. for 2019, 2020, and the five-year average. Diesel and fuel oil use did drop sharply in the early months of the pandemic, down about 25 percent year-over-year in late April, but this was nowhere near as severe as the drop in gasoline and ethanol. In addition, diesel and fuel oil use recovered to near 2019 levels by the end of the summer. This makes sense because diesel use, which directly impacts biodiesel use, was less affected by the lockdowns due to the pressure to keep freight moving in order to continue the flow of goods in the economy.

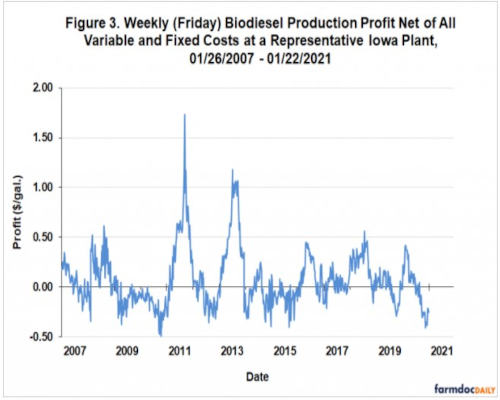

With that background we can proceed to discussion of biodiesel production profits. Figure 3 presents the weekly (pre-tax) estimates of biodiesel profits over January 26, 2007 through January 22, 2021 based on the price data and model assumptions. Two enormous spikes in 2011 and 2013 dominate the weekly profitability estimates, when profits exceeded $1 per gallon. There were also spikes in profitability in 2016 and 2018, but the peaks were smaller, reaching about $0.50 per gallon, but still notable. The average level of profits in 2011, 2013, 2016, and 2018 was $0.43, $0.50, $0.15, and $0.23 per gallon, respectively. By comparison, the average level of net profits in 2020 was -$0.001 per gallon, almost exactly at a breakeven level. This followed a net profit of -$0.02 per gallon in 2019.

With that background we can proceed to discussion of biodiesel production profits. Figure 3 presents the weekly (pre-tax) estimates of biodiesel profits over January 26, 2007 through January 22, 2021 based on the price data and model assumptions. Two enormous spikes in 2011 and 2013 dominate the weekly profitability estimates, when profits exceeded $1 per gallon. There were also spikes in profitability in 2016 and 2018, but the peaks were smaller, reaching about $0.50 per gallon, but still notable. The average level of profits in 2011, 2013, 2016, and 2018 was $0.43, $0.50, $0.15, and $0.23 per gallon, respectively. By comparison, the average level of net profits in 2020 was -$0.001 per gallon, almost exactly at a breakeven level. This followed a net profit of -$0.02 per gallon in 2019.

The average profit in 2020 obscures the rollercoaster nature of biodiesel production profits in 2020. The year started off well, with net profits peaking in early March at $0.42 per gallon, which was near the top of the range of profits since 2014. Profits quickly slid during the onset of the pandemic and fell all the way back to breakeven by the end of the summer. The bottom fell out starting in August, and losses by the end of the year were among the worst over the entire sample period. In early December, losses reached $0.41 per gallon. What makes this episode even more remarkable is that the losses were severe enough to drive the representative biodiesel plant into shutdown territory for an extended period of time. We define the shutdown price to be a biodiesel price net of marketing costs that is not high enough to cover variable costs of production. In fact, biodiesel prices were below the estimated shutdown price for 15 consecutive weeks from October 16, 2020 through January 22, 2021. This is by a very wide margin the longest period that biodiesel prices have been below the shutdown price since 2007. The rollercoaster ride for the U.S. biodiesel industry in 2020 was truly momentous.

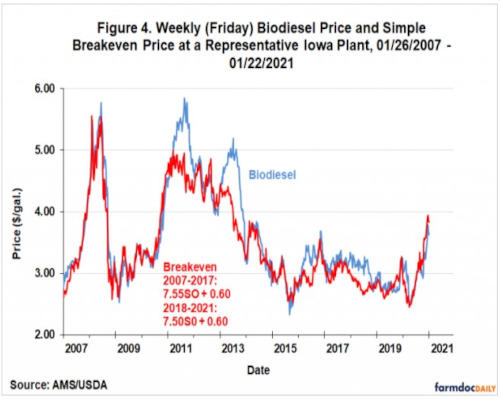

Further insight into the drivers of biodiesel profits is provided in Figure 4. Here, the biodiesel price at Iowa plants is plotted versus a simplified breakeven profit relationship between soybean oil and biodiesel prices. Since soybean oil represents over 80 percent of the variable operating costs of the representative plant, all other costs are lumped into the constant term of 0.60, or 60 cents per gallon of biodiesel produced. The 7.55 slope is just the number of pounds of soybean oil assumed to produce a gallon of biodiesel over 2007 through 2017. This is changed to 7.50 pounds for the following years. The breakeven relationship tracks the biodiesel price reasonably closely in 10 of the 14 years in the sample. The exceptions are 2011, 2013, 2016, and 2018. Outside of these years, the market generally priced biodiesel based on the cost of soybean oil, a partial markup for other variable and fixed costs, and small profits or losses. Implicit in this formulation is the idea that soybean oil prices lead (or cause) biodiesel prices at the weekly time horizon (farmdoc daily, September 10, 2015).

The spike in profitability during 2011, 2013, and 2016 can be directly traced to the race by diesel blenders to take advantage of the $1 per gallon blender tax credit that expired at the end of those calendar years. The key is that blenders face a binding RFS biodiesel mandate, and it is rational to effectively purchase biodiesel at a discount in the current year, due to the tax credit, in order to meet mandates in later years. Once the tax credit expires, the incentive to push up prices, profits, and production disappears and the biodiesel industry in the past returned to a norm of losses. This cycle, of course, depends on blenders perceiving there is substantial uncertainty whether the tax credit will be reinstated or not for the following year.

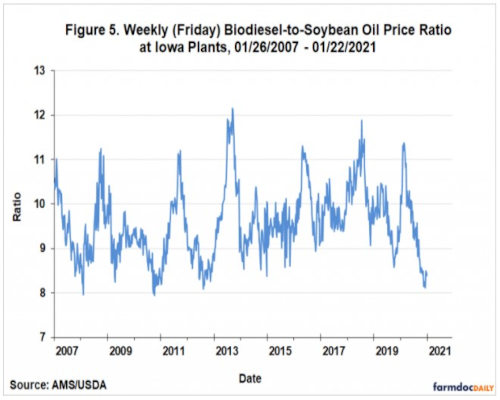

Since the biodiesel tax credit was in place for all of 2020, the movement of biodiesel prices and profits for 2020 cannot be explained by anything to do with the tax credit. Instead, the key is the large rise in soybean oil prices that began in April 2020. This is shown in the chart as an increase in soybean oil feedstock cost from an historical low of $2.46 per gallon in late April to a peak of $3.92 at the end of December. This is an increase of 60 percent in feedstock costs. Biodiesel prices also increased over this time period, but just not as fast as soybean oil prices. This is highlighted in Figure 5, which shows the weekly ratio of biodiesel and soybean oil prices at Iowa plants over January 26, 2007 through January 22, 2021. At the end of 2020, that ratio was just a bit more than eight, right at the lows for the ratio since 2007.

It should now be clear that the large losses of biodiesel producers in the latter part of 2020 can be traced to surging feedstock prices that outpaced the gains in biodiesel prices. This was unusual behavior that is not easy to explain. As noted earlier, previous research indicates that soybean oil prices lead (or “cause”) biodiesel prices at the weekly time horizon (farmdoc daily, September 10, 2015). In the past, increases in soybean oil prices have generally lead to increases in biodiesel prices that at least allow producers to breakeven. The behavior of biodiesel prices is even more of a riddle given that there has been no major biofuel policy changes during 2020. One possibility is a rising level of renewable diesel capacity and production in the U.S. It is possible that this is cannibalizing some of the demand for biodiesel. However, D4 RIN generation for all types of renewable diesel were only up six percent in 2020 compared to 2019. There was more of a surge in D4 renewable diesel generation in the last four months of 2020, but it was still only up eight percent year-over-year. Therefore, it does not seem probable that renewable diesel production is the culprit. Lacking a better explanation, biodiesel prices will in all likelihood have to rise to match the increase in feedstock prices. Otherwise, biodiesel production will decrease as plants shut down and this seems inconsistent with the demands for biodiesel under the RFS going forward. It is likely that the policy environment will be more favorable for increasing biodiesel production under the new Biden Administration.

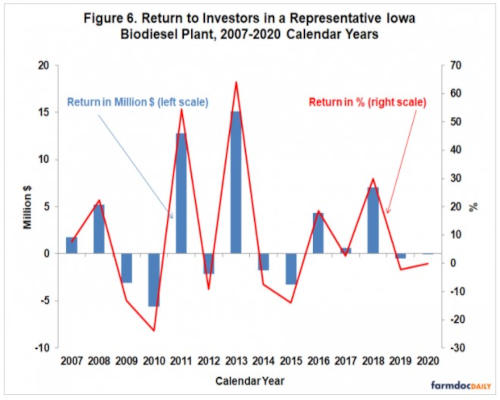

Another perspective is provided by aggregating profit margins over an annual horizon. Figure 6 shows total annual (pre-tax) profits net of variable and fixed costs for each calendar year between 2007 and 2020. Profits are presented in terms of both total pre-tax net returns and percent return to equity. The total profit of the representative biodiesel plant in 2020 was -$15,380, or a return of -0.1 percent. This was the second consecutive year of negative annual profits. We can also use the average net loss for the representative plant to make a rough estimate of the loss for the entire U.S. biodiesel industry in 2020. Assuming all plants in the industry earned a net profit of -$0.001 per gallon, then, total biodiesel production for the U.S. in 2020 of 1.809 billion gallons implies aggregate industry (pre-tax) profits of -$1.8 million.

The average percent return to equity holders provides useful information on the attractiveness of investment in biodiesel plants relative to other investments. The average return was 9.3 percent over 2007-2020 and the standard deviation, a measure of risk, was 25.9 percent. By comparison, the average return for the stock market over this period, as measured by the S&P 500, was 10.9 percent and the associated standard deviation was 17.5 percent. The ratio of average return to standard deviation provides one measuring stick of an investment’s return-risk attractiveness, and on this measure the ratio for biodiesel investment, 0.36, is somewhat lower than the stock market as a whole, 0.62.

Finally, it is important to note that the annual profit estimates do not take into account revenue from retroactively reinstated biodiesel tax credits. In response to the retroactive reinstatement of the $1 per gallon blenders tax credit, sharing clauses are included in many marketing contracts between biodiesel producers and blenders. These clauses specify how the biodiesel tax credit will be shared between the biodiesel producer and blender if the tax credit is not in place at the time a transaction is made but retroactively reinstated at some later date. There is no public data on the exact nature of the sharing provisions or the frequency that such provisions are put in place. Anecdotal evidence suggests sharing provisions are widespread and that the typical split of the $1 per gallon credit is 50/50. We have previously shown (e.g., farmdoc daily, February 5, 2020) that this additional tax credit revenue, garnered through sharing agreements with blenders, can yield a dramatically more positive long-term picture of the profitability of U.S. biodiesel production.

Implications

We estimate that a representative Iowa biodiesel plant broke even in 2020, despite the effects of the COVID pandemic and associated severe economic contraction. However, this is definitely a case where the average obscures the most interesting part of the story. The year started off well, with net profits peaking in early March at $0.42 per gallon, which was near the top of the range of profits since 2014. Profits quickly slid during the onset of the pandemic and the bottom fell out starting in August. Losses by the end of the year were among the worst over the entire sample period. The losses were severe enough to drive the representative biodiesel plant into shutdown territory for an extended period of time. In fact, biodiesel prices were below the shutdown price for 15 consecutive weeks from October 16, 2020 through January 22, 2021. This is by a very wide margin the longest period that biodiesel prices have been below the shutdown price since 2007. The driving force behind the historic losses late in the year was skyrocketing soybean oil prices that outpaced gains in biodiesel prices. This situation is unsustainable. Either a large number of biodiesel plants will have to be shutdown, which runs counter to expected needs for biodiesel to fulfill the RFS mandates, or the price of biodiesel will have to increase to catch up with soybean oil prices.

Source : illinois.edu