As part of the Biden Administration’s broad $33 billion proposal to provide aid to Ukraine and address war related problems, the Administration included $500 million for domestic food production assistance to incentivize production of U.S. food crops experiencing a global shortage due to the war in Ukraine. About $400 million would go toward higher loan rates for wheat, rice, pulse crops, and edible oilseed crops for two years. About $100 million would be used to incentivize double-crop soybean production, with a $10 per acre crop insurance premium benefit for 2023 soybeans planted after planting winter wheat in the fall of 2022. The proposal needs Congressional approval and is likely to be amended in that process.

Marketing Assistance Loan Program

Part of the US farm safety net is the Marketing Assistance Loan (MAL) program. This program is authorized as a commodity program in Title I of the farm bill. Congress specifies the loan rate for each eligible commodity. Corn, soybeans, and wheat are among the eligible commodities. MAL has two features that potentially benefit farmers.

The first feature is that the loan rate serves as the floor price for the harvested commodities eligible for MAL. Should cash market prices decline below the loan rate, a farmer receives assistance on the difference. This assistance can come in one of two types: a Loan Deficiency Payment (LDP) or a Marketing Loan Gain (MLG). Both provide the farmer with a per unit gross income return; the LDP is a direct payment while the MLG is a reduced repayment on the loan, permitting the farmer to keep the difference. Loan rates are established by Congress in the farm bill and posted county prices determine whether assistance is triggered.

Farmers of loan eligible crops may take out a loan on the harvested bushels on hand or apply for an LDP in lieu of the loan. The loan amount equals the per unit loan rate times the number of units placed under loan. The farmer has use of this loan amount for up to nine months. A common use of this loan is to pay off higher interest loans, or in economic terms to arbitrage between the MAL interest rate and the interest rate on the farm’s loans. MAL loan rates are often obtained at harvest when market prices tend to be at seasonal lows and producers tend to have large cash flow needs, providing an option to delay sale of the crop in anticipation of more favorable market conditions.

The MAL loan plus any accrued interest can be repaid at any time during the loan period. The commodity loan can be repaid in cash, if the market prices are below the loan rate the repayment is adjusted to the lower price and the farmer keeps the difference. This feature was revised in the 1990s for all crops to avoid forfeitures that had long plagued the program, with the CCC holding billions in forfeited commodities during the 1950s, 1960s and 1980s. Defaulting was historically the method for repaying loans if market prices were below the loan rate, but alternative approaches were developed in an effort to prevent the delivery of the commodities to CCC. These alternatives are the previously discussed LDP and MAL deficiency payments.

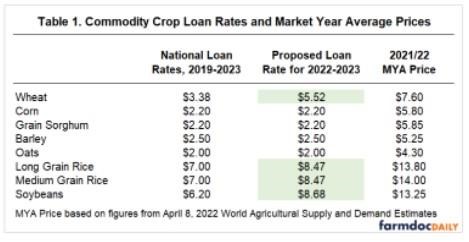

Under the Biden proposal, the loan term for MAL would be extended from nine to twelve months and the loan rate would increase for specific crops (see Table 1). For wheat, the national loan rate would increase 63% from $3.38 to $5.52 per bushel. Pulse crop loan rates would increase 21% and oilseed loan rates would increase 40%, pushing the soybean national loan rate from $6.20 to $8.68 per bushel. All proposed loan rate increases would be well below the current market year average prices. Though relatively large shares of production were put under MAL in the 1990s through early 2000s (see farmdoc daily June 8, 2017), data from FSA and NASS indicates only 3% of total U.S. wheat and soybean production has been put under MAL loan annually, on average, over the past five years.

Because projected market prices are well above the proposed higher loan rates, it is expected that any MAL would likely be taken out as an interest rate arbitrage, using the lower interest rate MAL to pay off an existing higher interest rate loan. The use of this arbitrage is likely to expand as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates and the cost to borrow rises. The interest rate for MAL is 1% above the CCC’s cost of borrowing from the US Treasury, lower than typical lender operating loan rates (see USDA FSA Notice). The rate is 2.75% for MAL loans taken out in May 2022 (see USDA May 2022 Announcement). The higher loan rates increase the amount that can be borrowed on a given quantity of the crop and the proposed extension of the MAL loan period to 12 months provides for longer use of the low-cost financing.

While the loans could be attractive to farmers as a temporary financing alternative, their impact on production will be driven by the relationship between the market price and loan rate. Despite the large percentage increase proposed, loan rates would remain below current market prices. As long as this condition exists, it is unlikely that the higher loan rates will impact cropping decisions and thus acres planted to the crops with higher loan rates.

Double-Crop Soybeans Insurance Incentive

About $100 million in the proposal is to incentivize double cropping soybeans after wheat. Crop insurance premiums on 2023 double-crop soybeans following 2022 planted winter wheat would be reduced by $10 per acre.

A designation as a “following another crop” (FAC) practice is needed to obtain crop insurance on a second crop in a single crop year. For soybeans, the FAC designation is currently available only in certain counties (see Figure 1). In 2021, there were 2.5 million double-crop soybeans insured, representing 2.8% of the 89.7 million acres of soybeans insured. The five largest double-crop soybean states were Kansas (609,000 acres), Illinois (397,000 acres), Kentucky (380,000 acres), Missouri (285,000 acres), and Tennessee (282,000 acres). In counties where double-crop soybeans are an approved FAC practice, farmers who purchase crop insurance for full season soybeans must insure FAC soybeans in that same county.

Farmers in counties without a FAC for double-crop soybeans have the option to not insure the FAC soybeans or obtain a written agreement permitting the purchase of crop insurance for double-crop soybeans. In this situation, farmers may opt to not purchase insurance on the double-crop soybeans, especially if they do not already have a crop history of double-crop soybeans. Without a yield history, transitional yields (T-yields) would be used in guarantee yield calculations, and use of T-yields typically result in very low guarantee yields.

There are acres not being double-cropped in areas where double-cropping is possible. Central Illinois is an example of a location where wheat is not commonly grown but could be, though many central Illinois counties do not have a FAC practice. Farmers in this region could transition to double-crop by growing winter wheat followed by the soybeans instead of planting full season soybeans or corn.

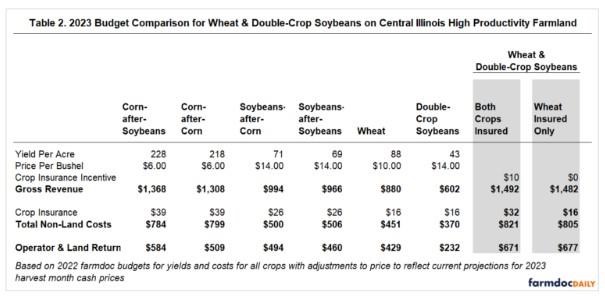

Farmer adaptation will depend on expected relative profitability. To provide an example of budget comparisons, we use costs and yields from the 2022 Illinois budgets (see farmdoc 2022 Budgets), and adjust price to reflect current projections for cash prices in the 2023 harvest month for each crop as shown in Table 2. Using this budget example, a central Illinois farmer could get higher operator and land return from winter wheat planted in fall 2022 plus double-crop soybeans planted in spring 2023, as compared to growing full season soybeans or corn in 2023. Corn grown in 2023 following a 2022 soybean crop is the full season single-crop option with the largest projected operator and land return, at $584 per acre.

Now consider projected returns for wheat plus double-crop soybeans under two scenarios: one with crop insurance on the double-crop soybean and one without insurance. The crop insurance premium for wheat is $16 per acre and the premium for double-crop soybeans is $16 per acre, higher than the $10 per acre proposed incentive. If able to obtain crop insurance on double-crop soybeans, the $10 incentive would partially offset the $16 policy premium, resulting in a $6 per acre cost bringing operator and land return to $671 per acre. Without crop insurance on the double-crop soybeans, a farmer would forgo the $10 incentive, but would not owe the $16 premium cost for the double-crop soybeans, resulting in an operator and land return of $677 per acre. Without crop insurance on the double-crop soybeans, net returns are $6 higher than with insurance assuming the estimated prices and trend yields. Regardless of crop insurance, wheat plus double-crop soybeans result in projected returns that are at least $87 per acre larger than the next highest alternative.

Currently the market is providing very strong signals which encourage double-crop wheat and soybeans. The value of the $10 per acre crop insurance discount is very minimal compared to the incentive to double-crop provided by the market. Further, obtaining crop insurance on the double-crop soybeans may be an undesirable expense for farmers outside of FAC provisions and without a yield history. If an increase in double-crop wheat and soybeans occurs, it’s likely attributed more strongly to market signals than a $10 per acre incentive that also requires a purchase of a crop insurance policy that costs more than the incentive and isn’t readily available to all farmers who could double-crop.

Analysis

Although the goal of increasing farm commodity production is desirable, the proposal faces a number of constraints:

- The proposed increase in loan rates is not likely to impact the production of the crops in the current price environment.

- A transition to more double-crop acres would increase production of both wheat and soybeans, but the $10 per acre crop insurance incentive is minimal compared to the net returns the market is currently offering, particularly when the cost and availability of purchasing crop insurance on double-crop soybeans is considered. Is the proposed budget for this proposal better spent in a way that could more effectively increase production?

- Crop insurance for double-crop soybeans is currently only available in select counties without an extra step to obtain approval for purchase. Some ways of streamlining crop insurance outside of current double-crop soybean counties may be desirable. Streamlining likely would include developing rates so that farmers would know premiums without going through a written agreement process.

- Although a precedent exists with the premium incentive for planting cover crops, an important policy question exists: “Should the crop insurance program be used for policy initiatives not directly related to farm risk?”

- The proposal notably excludes corn. Ukraine is one of the top four producers of corn and contributes over 15% of the world corn exports (see farmdoc daily February 28, 2022). The market indicates more corn is needed and corn is a substitute commodity for wheat. All these considerations suggest a production enhancing proposal should also include corn and other feed grains.

- While excluding corn, the proposal includes rice. Ukraine is not a significant contributor to the world market for rice; over the past five years Ukraine has accounted for 0.01% of the world’s rice production and rice exports (Data Source: USDA-FAS PSD). Rice can be a substitute for food crops experiencing a global shortage due to the war in Ukraine. However, producers cannot easily expand rice production unless already equipped for rice production while the same equipment can be used to grow corn, soybeans, and wheat with small modifications.

- Delayed planting is a potential threat to production in 2022 raising the possibility for prevent plant acreage (see farmdoc daily May 3, 2022 and May 4, 2022). If acres are unable to be planted and late plantings reduce yield potential, the US will face production shortfalls in opposition to production enhancing efforts. The US may consider policy changes to encourage late planting when possible. Strategies will be proposed in Friday’s farmdoc daily article.

Source : illinois.edu