The pig has a digestive system which is classified as monogastric or nonruminant. Humans also have this type of digestive system. They have one stomach (mono=one, gastric=stomach). The monogastric differs from that of a polygastric or ruminant digestive system found in cattle and sheep. These animals have one stomach broken into four compartments. Due to the differences in the digestive systems, cattle can utilize different types of feeds than pigs. Cattle and sheep can live on hay and pasture, while pigs must eat grains that can be digested more easily.

Digestion is the break-down of food occurring along the digestive tract. The digestive tract may be thought of as a long tube through which food passes. As food passes through the digestive tract, it is broken down into smaller and smaller units. These small units of food are absorbed as nutrients or pass out of the body as urine and feces.

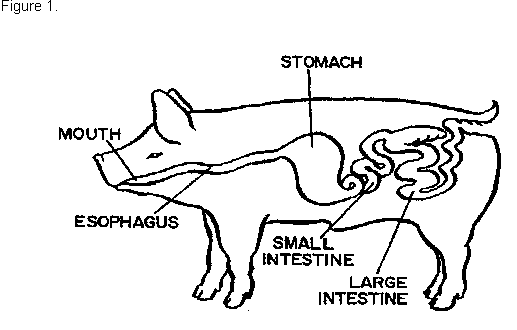

The digestive tract of the pig has five main parts: the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines ( Figure 1 ). The following discussion explains how each part digests nutrients.

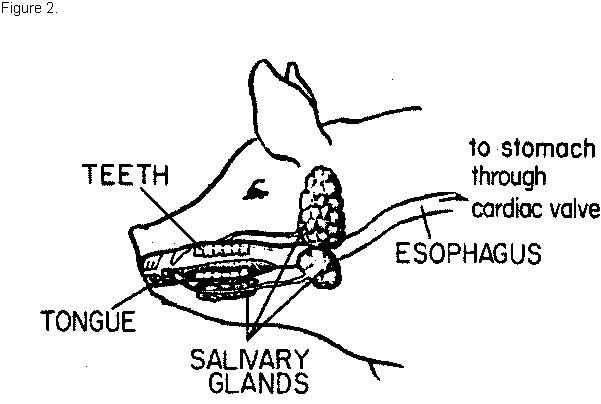

The mouth is where food enters the digestive tract and where mechanical breakdown of food begins ( Figure 2 ). The teeth chew and grind food into smaller pieces. Saliva , produced in the mouth, acts to soften and moisten the small food particles. Saliva also contains an enzyme which starts the digestion of starch. The tongue helps by pushing the food toward the esophagus .

The pig has a digestive system which is classified as monogastric or nonruminant. Humans also have this type of digestive system. They have one stomach (mono=one, gastric=stomach). The monogastric differs from that of a polygastric or ruminant digestive system found in cattle and sheep. These animals have one stomach broken into four compartments. Due to the differences in the digestive systems, cattle can utilize different types of feeds than pigs. Cattle and sheep can live on hay and pasture, while pigs must eat grains that can be digested more easily.

Digestion is the break-down of food occurring along the digestive tract. The digestive tract may be thought of as a long tube through which food passes. As food passes through the digestive tract, it is broken down into smaller and smaller units. These small units of food are absorbed as nutrients or pass out of the body as urine and feces.

The digestive tract of the pig has five main parts: the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines ( Figure 1 ). The following discussion explains how each part digests nutrients.

The mouth is where food enters the digestive tract and where mechanical breakdown of food begins ( Figure 2 ). The teeth chew and grind food into smaller pieces. Saliva , produced in the mouth, acts to soften and moisten the small food particles. Saliva also contains an enzyme which starts the digestion of starch. The tongue helps by pushing the food toward the esophagus .

Figure 2.

The esophagus is a tube which carries the food from the mouth to the stomach. A series of muscle contractions push the food toward the stomach. Swallowing is the first of these contractions. At the end of the esophagus is the cardiac valve, which prevents food from passing from the stomach back into the esophagus.

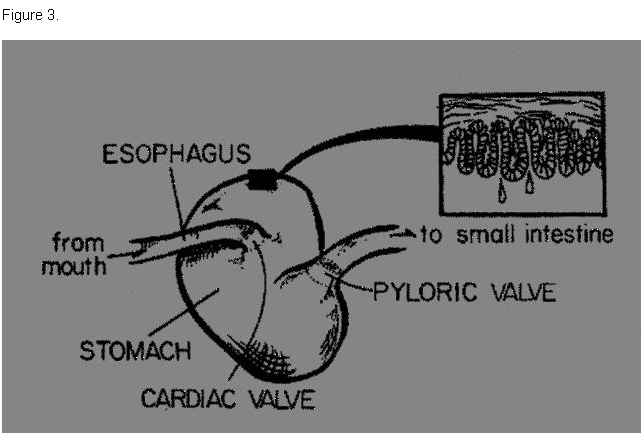

The stomach is the next part of the digestive tract ( Figure 3 ). It is a reaction chamber where chemicals are added to the food. Certain cells along the stomach wall secrete hydrochloric acid and enzymes. These chemicals help break down food into small particles of carbohydrates , protein , and fats . Some particles are absorbed from the stomach into the bloodstream. Other particles which the stomach cannot absorb pass on to the small intestine through the pyloric valve .

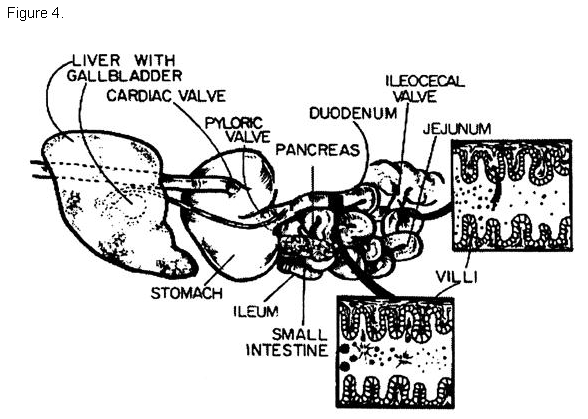

The small intestine is a complex tube which lies in a spiral, allowing it to fit in a small space ( Figure 4 ). Its wall has many tiny finger-like projections known as villi , which increase the absorptive area of the intestine. The cells along the small intestine's wall produce enzymes that aid digestion and absorb digested foods.

At the first section of the small intestine (called the duodenum ) secretions from the liver and pancreas are added. Secretions from the liver are stored in the gall bladder and pass into the intestine through the bile duct. These bile secretions aid in the digestion of fats.

Digestive juices from the pancreas pass through the pancreatic duct into the small intestine. These secretions contain enzymes that are vital to the digestion of fats, carbohydrates, and proteins.

Most food nutrients are absorbed in the second and third parts of the small intestine, called the jejunum and the ileum . Undigested nutrients and secretions pass on to the large intestine through the ileocecal valve.

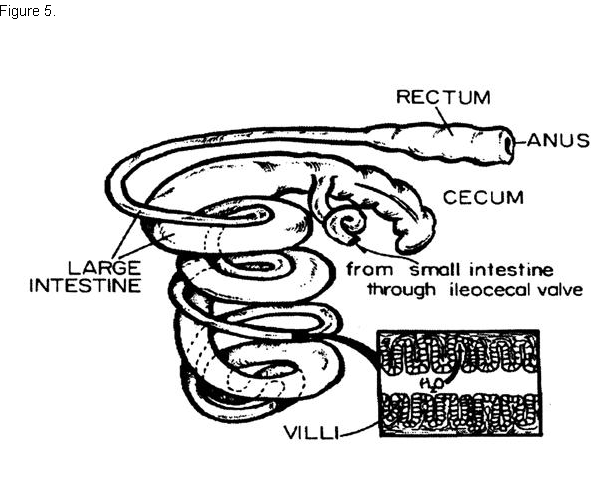

A "blind gut" or cecum is located at the beginning of the large intestine ( Figure 5 ). In most animals, the cecum has little function. However, in animals such as the horse and rabbit, the cecum is very important in the digestion of fibrous feeds.

The last major part of the digestive tract, the large intestine, is shorter, but larger in diameter than the small intestine. Its main function is the absorption of water. The large intestine is a reservoir for waste materials that make up the feces. Some digestion takes place in the large intestine. Mucous is added to the remaining food in the large intestine, which acts as a lubricant to make passage easier. Muscle contractions push food through the intestines. The terminal portion of the large intestine is called the rectum .

The anus is an opening through which undigested food passes out of the body. Food that enters the mouth and is not digested or absorbed as it passes down the digestive tract is excreted through the anus as feces.

This was a general discussion of the digestive tract of the pig. The tract acts to digest and absorb nutrients necessary for maintenance of cells and growth. Efficient absorption of nutrients depends on each segment of the digestive system functioning to its maximum capacity.

Source: University of Florida