“It can be very, very bountiful or it can be the complete polar opposite and be a famine,” Tanner said. “You have to learn how to weather those storms in life.”

Recently, those storms have been closer to a Dust Bowl than a deluge.

After the rain shut off last spring, most of his wheat fields in northern Norton County ended up producing fewer than 20 bushels per acre, a steep drop from his average yields. Many of them didn’t grow enough to bother harvesting at all.

It’s been a historically hot, dry, windy year across western Kansas. As incessant drought, sweltering heat waves and relentless winds have pummeled the region’s fields, gaining a better understanding of extreme weather’s impact on wheat has become increasingly critical for farmers and the state’s multibillion-dollar agricultural economy.

As the country’s top wheat-producing state — growing roughly one-fifth of all the wheat in the U.S. — the pain wheat farmers feel here sends ripple effects across the globe.

Triple whammy

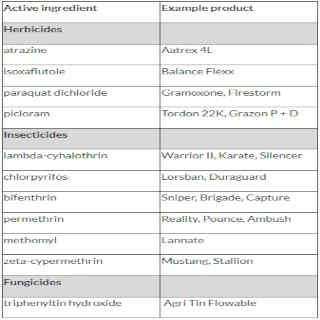

The landmark K-State study bills itself as the first one to compute the impact of a changing climate on wheat farming in the Great Plains. It analyzed how different combinations of weather add up to affect the grain’s production across six states — Kansas, Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, Oklahoma and Texas.

The goal was to answer some simple questions with four decades of detailed data. What happens to wheat when the weather is hot? Or dry? Or windy? And what about when two or three of those atmospheric conditions hit the same field at the same time?

Unsurprisingly, the triple whammy of hot, dry and windy weather — known as HDW events — inflicted the most damage on harvests.

K-State agronomy professor Stephen Welch ran the study’s theoretical modeling that showed how various climate conditions impact plant growth. The compound impact of those three extremes happening together, he said, is significantly greater than when they occur one at a time. And in the Great Plains, those HDW events are ramping up.

That’s specifically tied to when HDW events happen during the critical latter stages of the plant’s growth. In Kansas, wheat generally hits that time of flowering and ripening during the spring.

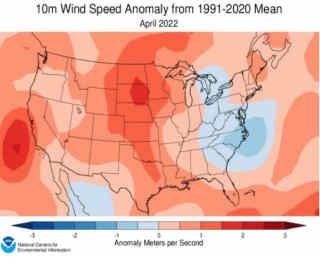

Unfortunately, that’s also the time when Kansas winds tend to whip the fiercest. On average, April is the windiest month of the year in Kansas. And the gusts blew especially hard last year. Goodland and Salina experienced their windiest April on record.

The number of HDW weather events significantly increased during the study’s data period from 1982-2022 as greenhouse gas emissions warmed the climate.

And the places that saw the sharpest rise in the frequency and severity of these events were the same ones that endured the Dust Bowl nearly a century ago, including western Kansas. The southern High Plains is already the windiest region in the inland U.S. and one of the driest regions east of the Rockies based on historical averages. So it makes sense that small, incremental changes in climate would be felt acutely here.

Kansas State University professor and state climatologist Xiaomao Lin, who led the research team, said the study expects these HDW events to become even more frequent, intense and persistent as climate change continues over the next 25 to 75 years.

Click here to see more...