In order to set the cutoff date for late corn planting in the U.S., we follow our previous work on the topic (e.g., farmdoc daily, May 20, 2015; April 24, 2019; May 13, 2020). The cutoff date is based on agronomic field trials relating planting date to corn yields at the farm-level (e.g., farmdoc daily article, April 14, 2022), which indicates that yield penalties become increasingly large as planting is delayed after mid-May. As before, we define the beginning date for substantial late planting penalties on corn yield in the U.S. to be May 30th from 1980 through 1985 and May 20th from 1986 onwards. The change in cutoff dates in the mid-1980s reflects recommendations for earlier planting that appeared around that time.

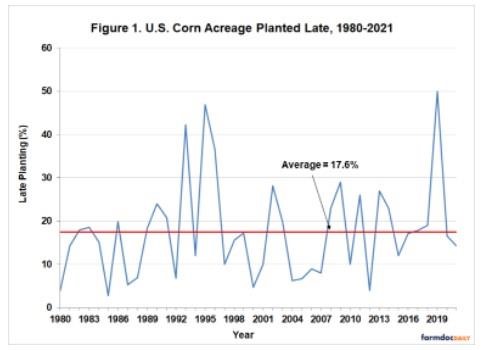

Figure 1 shows the percentage of corn planted late in the U.S. based on these definitions over 1980 through 2021. On average, late planting was 17.6 percent, with the bulk of the observations between about 5 and 25 percent. The extraordinarily high level of late planting in 2019 is obvious. At 50 percent, this was the highest level of late planting over the 42-year sample period. There were only two other years (1993 and 1995) when late planting exceeded 40 percent. Finally, there is no evidence of a trend up or down over time in the late planting percentage, which suggests that producer behavior in aggregate with respect to late corn planting has been quite stable (after adjusting for earlier planting through time).

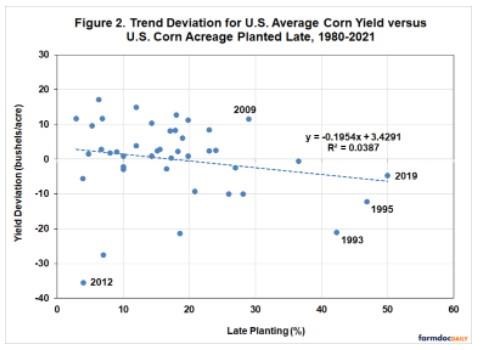

The next step of the analysis is to estimate the impact of late planting on the U.S. average corn yield. Figure 2 show the relationship between the trend deviation for U.S. corn yield and corn acreage planted late over 1980 through 2021. The trend deviation is computed based on a linear trend for U.S. average corn yields over this period. The figure shows that, as expected, there is an overall negative relationship between late planting and corn yield deviations from trend. Specifically, for a 10 percent increase in late planting the U.S. average corn yield decreases by about 2 bushels per acre. It is also interesting to consider the implication of the intercept estimate of the regression model. It implies that when late planting is zero the increase in corn yield above trend is 3.4 bushels. This is the maximum benefit of early planting on the U.S. average yield of corn according to this regression model. In comparison, the maximum loss in yield from high levels of late planting can be much larger. For example, the model predicts that the 50 percent level of late planting in 2019 leads to a 6.3 bushel decline below trend for the U.S. average corn yield.

It is important to emphasize that the explanatory power of the regression model in Figure 2 is quite low, as the R2 is only 3.9 percent. Because of this low explanatory power, the regression model in Figure 3 should be treated with a good deal of caution. This does not mean that late planting should be ignored when projecting corn yield, but rather, other factors, in particular summer weather, are much more important in explaining deviations from trend yield (e.g., Nielsen, 2015). Two years provide good examples. Late planting was well-above average in 2009 but the corn yield was a record at the time due to a cool, wet summer. Conversely, late planting in 2012 was at the very low end of the sample range but corn yield was extremely low relative to trend due to the severe drought that summer.

Since several factors influence the magnitude of the U.S. average corn yield in any given year, particularly summer weather conditions, it is important to jointly consider all of the relevant factors in order to quantify the impact of late planting. In technical terms, this means that the regression model in Figure 2 may suffer from “omitted variable bias.” We addressed this problem by estimating a crop weather regression model in earlier work (farmdoc daily, May 13, 2020) that relates the U.S. average corn yield to trend, the percentage of the crop planted late, and an array of weather variables. The regression model estimates indicate that the U.S. average corn yield decreased by 2.2 bushels per acre for each 10 percent of the crop that is planted late, very close to the estimate from the simple bivariate model presented in Figure 2. For all practical purposes, they are nearly the same at about -0.2.

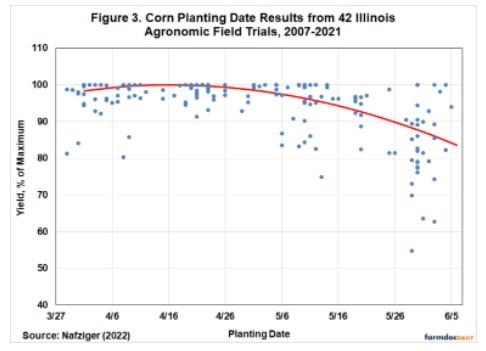

A final issue is the apparent small size of the late planting impact estimated for the U.S. average corn yield found in Figure 2 compared to the late planting impacts from agronomic field trials. For comparison, Figure 3 shows the results of agronomic field trials for corn planting dates in Illinois that was presented in this recent farmdoc daily article (April 14, 2022). The trial data indicate that the yield of corn planted past mid-May can be reduced as much as 10 to 20 percent. If was assume a U.S. average trend yield for corn in 2022 of 179 bushels per acre, this could then be used to project yield reductions of 18 to 36 bushels per acre below trend for the corn planted past mid-May, with large resulting impacts on the U.S. average yield of corn. Or one could try to estimate an average yield penalty for the entire U.S. based on the planting date response curve in Figure 3. This would involve computing, say, the percentage of the corn crop planted before and after mid-May, and then imposing the average yield penalty in those two periods from Figure 3.

While it is tempting to map yield penalties from agronomic field trials directly to projections of the U.S average yield for corn this is not appropriate for several reasons. First, the planting trial results are specific to particular planting dates, whereas the U.S. late planting variable is the percentage of the crop planted after a particular cutoff date. Second, the planting trial results are reported as the percentage of maximum yield in a test location for the given year, which is not the same as deviation from trend yield. The maximum trial yield in any year can be far above or below trend yield for the state or the entire U.S., and the maximum varies across trial locations. Third, the planting trial results, while thought to be representative, are still state and location specific.

The agronomic field trials are obviously the gold-standard for farmers deciding when to plant corn in a state or region. However, the previous discussion suggests the yield penalties reported in these experimental studies were never meant to be mapped directly into trend deviations for the U.S. average yield of corn. If one is interested in yield deviations at the national level, which is key for grain markets, the only recourse is to use some kind of measure of late planting for the entire U.S. When one does this, as we did with the regression model in Figure 2, the U.S. average yield of corn shows a surprisingly small impact from late planting. Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is to consider the average trend deviation when sorting the data into thirds based on the level of late planting. The one-third of years in the lower range of late planting (average = 6.8 percent) were on average -1.1 bushels below trend; the one-third of years in the middle of the range of late planting (average = 16.1 percent) were on average +3.5 bushels above trend; and the one-third of the years in the higher range of late planting (average = 29.7 percent) were on average -2.4 bushels below trend. Whether one is in the lowest third of late planting or highest third, the difference in yield deviations is not much more than three bushels.

There is, of course, always the possibility that our selected measure of late planting is a poor measure of impacts on the U.S. average yield of corn. We have tested numerous measures in the last 15 years (e.g., Irwin, Good, and Tannura, 2008) and have not been able to find a better one at the national level. Until compelling evidence of a better measure becomes available, we are left with the result that late-planting is very much a secondary consideration when projecting the U.S. average yield of corn. The big show remains summer weather.

Implications

In this article, we examine what we know about the impact of late planting on the U.S. average corn yield. Late planting is defined for as the percentage of the U.S. corn crop planted after May 20th (except for a few early years). We then estimate a regression model between corn acreage planted late and trend deviations for the U.S. average corn yield over 1980 through 2021. The results indicate a 10 percent increase in late planting decreases the U.S. average corn yield by about 2 bushels per acre. Overall, the impact of late planting is rather modest, causing the national corn yield to deviate above or below trend by no more than three bushels in most years. Other factors, namely summer weather, dominate the impact of late planting in determining the national average corn yield. Of course, there can be exceptions. For example, the model estimated that late planting in 2019 led to a 6.3 bushel decline below trend for the U.S. average corn yield. The lesson from this analysis for 2022 is that even if late planting is well-above average, the impact on the U.S. average corn yield is not likely to be large. But, even a five bushel drop in yield below trend will only further tighten what is already a tight supply/demand balance.

Source : illinois.edu