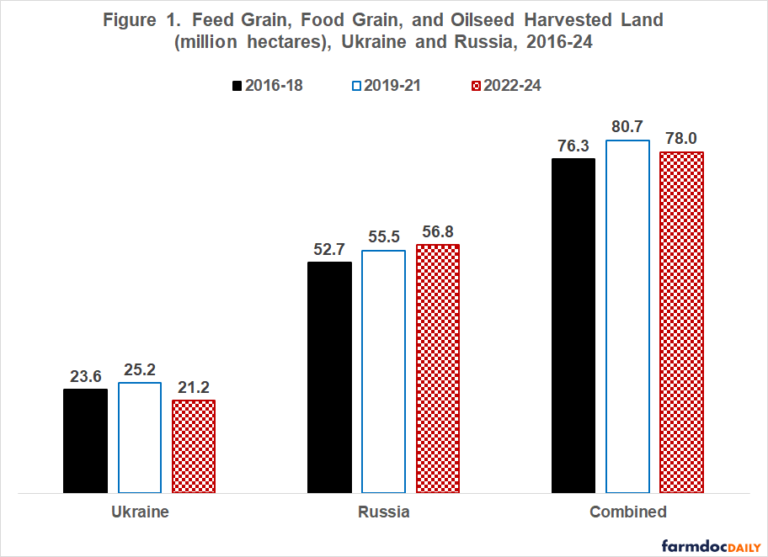

Ukrainian harvested feed grain, food grain, and oilseed land has been 16% lower during the war vs. 2019-21 (see Figure 1). Throughout most of the 21st Century prior to the war, harvested land had steadily increased in the Ukraine (USDA, FAS). Harvested land has increased in Russia since 2010. It continued to increase during the war (see Figure 1). Combined harvested land in Ukraine and Russia has been 3% less during the war vs. 2019-21.

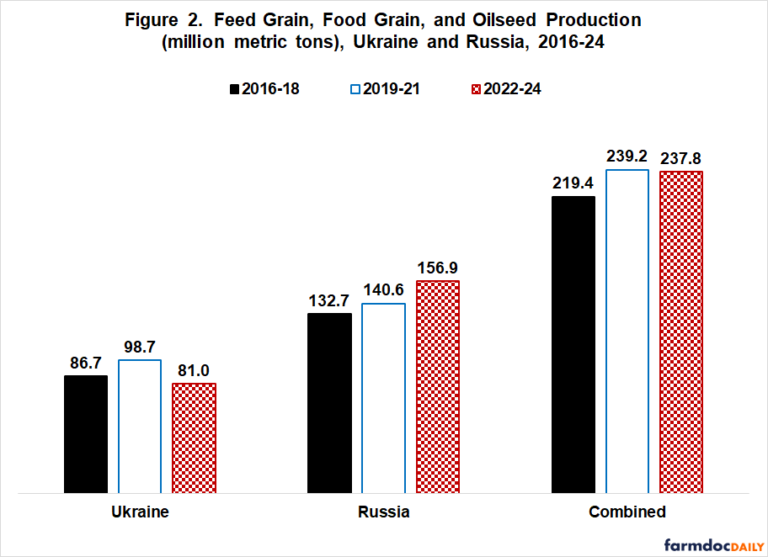

The 16% decline in Ukrainian harvested land largely explains the 18% decline in Ukraine’s production of grains and oilseeds during the war (see Figure 2). Aggregate grain-oilseed yield has only been 3% lower in 2022-24 than in 2019-21 (3.8 vs. 3.9 metric tons per hectare). In contrast, Russia’s aggregate grain-oilseed yield has been 12% higher during the war than in 2019-21 (2.8 vs. 2.5 metric tons per hectare). Due to both a higher yield and more harvested land, Russian grain-oilseed output has been 18% higher during the war vs. 2019-21. Combined Ukrainian-Russian grain-oilseed output has been only 1% lower during the war vs. 2019-21.

Individual Crops

The five crops with the highest production in Ukraine and Russia are examined separately. Combined production of soybeans in Ukraine and Russia was 45% higher in 2022-24 vs. 2019-21 (see Figure 3). Sunflower and wheat production was similar, down 2% and up 3%, respectively. In contrast, production of corn and barley was down 13% and 10%, respectively.

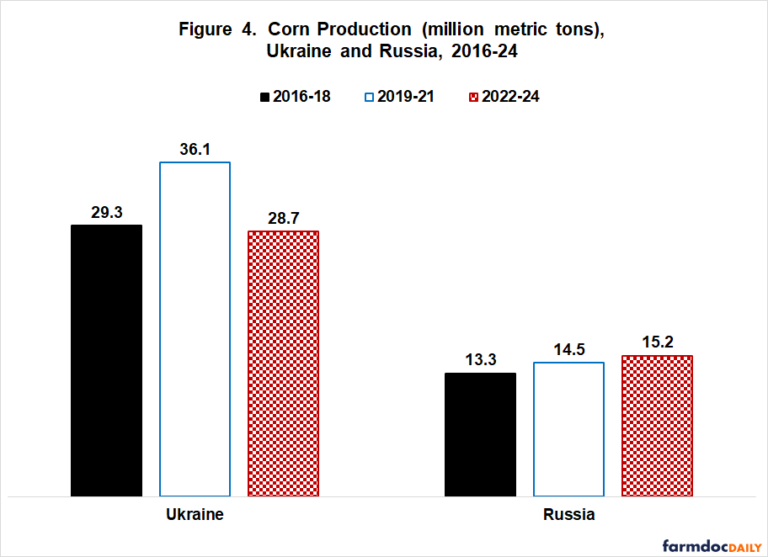

Corn

Corn production is examined further since its output declined the most. Ukraine accounted for all the decline (see Figure 4). Its production of corn was 20% lower in 2022-24 than in 2019-21, entirely due to a 22% decline in harvested corn land. In contrast, higher yields entirely accounted for the 5% increase in Russia’s corn output during the war vs. 2019-21. A 12% higher corn yield more than offset a 6% decline in harvested corn land in Russia.

Discussion

The Ukraine-Russia War has only slightly reduced combined grain and oilseed production in the two countries, the same conclusion reached in the farmdoc daily of November 27, 2023. Reasons include higher yields in Russia, probably due in part to favorable weather; only a slight decline in Ukraine’s yields, and increased harvested land in Russia.

In short, higher Russian production has largely offset lower Ukrainian production. If the fighting stops, it is reasonable to assume that land not planted in the area of fighting will return to production, some immediately and some over time.

A return to pre-war production levels in Ukraine will thus likely increase global supplies, suggesting downward pressure on prices is more likely than not.

To provide perspective on potential price pressure, assume Russian production of grains and oilseeds remains at its higher level during the war while Ukrainian production returns to its 2019-21 level. Annual output of grains and oilseeds in the two countries would be 7% higher.

Given the assumption in the previous point, production of corn, the crop most impacted by the war, would be 17% higher. This increase is unlikely to happen immediately, but will amount to 7 to 8 million metric tons, or 250 to 300 million bushels of additional corn output. The increase is between 3% and 4% of currently projected international trade in corn during the 2024 crop year, and is equivalent to a 3 to 4 bushel per acre increase in US average corn yield. It is reasonable to expect that Ukraine will be an aggressive exporter of agricultural products to fund post-war reconstruction.

While not the focus of this article, it is important to point out that an end to the Ukrainian-Russian War could lead to a reduction in tariffs and restrictions on US imports of potash and other fertilizers from Russia and Belarus, thus reducing their cost to US farmers (see farmdoc daily, March 17, 2022 and April 5, 2022; and Hebebrand and Glauber, April 5, 2024).

Source : illinois.edu