By Paul Solomon

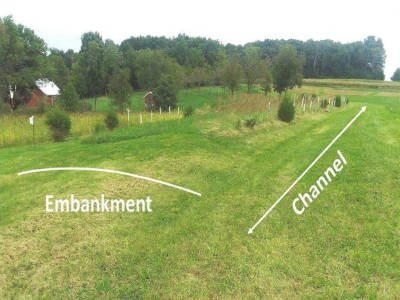

A diversion consists primarily of an earthen embankment, which is constructed with back and front slopes and contains a channel at its base to catch and slow runoff.

Recently I became the owner of an abandoned 21-acre York County farm, now called Timberidge Farms. This neglected property contained a number of both natural and man-made surfaces which were conduits for stormwater. This runoff had the potential to cause damage to my own property as well as to pollute local and regional waterways, including an adjacent stream. I considered the precipitation that fell on and traveled across my land to be both my responsibility and my opportunity. Introducing stormwater best management practices (BMPs) became one of my first priorities as the new property owner.

In order to determine which BMPs to consider, my first steps were to study prior stormwater damage and the quantity and direction of runoff following multiple intense storms. Damage was especially evident in the farm’s driveway, which was badly washed out. Stormwater rushed along this driveway during each heavy rainstorm, depositing pollutants into the adjacent stream. In places along the driveway, sediment from prior storms had been deposited. Capturing and retaining this water on-site would prevent property and ecological damage, while providing a plentiful water supply to support the farm’s well and any future rain gardens, ponds, and various landscaping enhancements.

Preventing stormwater damage to local waterways is particularly important. In my situation, the stream located adjacent to the farm is a first order, perennial, spring-fed stream. This watercourse exists as a tributary to Little Falls, which extends south through York County and into Baltimore County, MD. Little Falls, in turn, is a major tributary to the Gunpowder Falls, a major public water supply source for metropolitan Baltimore. These waterways are classified as cold water fisheries with exceptional water quality. In addition to their vital role in area water supplies, these waterways provide recreational opportunities to Pennsylvania residents and visitors and support native brown and brook trout populations.

To develop a stormwater mitigation strategy, I sought out the advice of the professionals at The Natural Resource Conservation Service(NRCS), located in York County. (Similar offices are located in most other Pennsylvania counties as well.) NRCS prepared a Soil Conservation Plan for my farm, which recommended a number of practices designed to reduce runoff. This expert technical advice, which was available free-of-charge, enabled me to prioritize and plan the various improvements so that the most important and impactful work was scheduled first. (While I did not make use of it, cost sharing for design and construction is also often available.) The NRCS technical experts designed a diversion as the first intervention.

A diversion consists primarily of an earthen embankment, which is constructed with back and front slopes and contains a channel at its base. This channel serves to catch, slow, infiltrate, and direct runoff into a spreader, or adjacent area of land, where the runoff can infiltrate slowly into the ground. In general, a diversion prevents or reduces soil erosion and concentrated runoff flows by “walking” the collected runoff along the channel, which is built at a 1 to 2 percent grade, to the spreader located at the end of the diversion. This outfall must be carefully designed to ensure that it will not cause erosion.

Timberidge Farms Diversion