By David Hensley & Diane Rowland

One of the primary benefits of growing legumes like peanut is their ability to convert nitrogen in the atmosphere to a form that is available for use throughout the plant. They do this by forming a symbiosis (a mutual “partnership”) with bacteria known as Rhizobia. When Rhizobia become associated with peanut roots, the plant and bacteria form a structure known as a nodule that houses the bacteria and creates the most beneficial conditions for the bacteria to thrive. The nodule is also the site where the fixed atmospheric nitrogen is delivered to the plant. Most of a legume’s nitrogen needs are supplied by the Rhizobia in its root nodules, and when nodules degrade either during the season or when the crop is harvested, some of that fixed nitrogen may become available to the following crop. However, one barrier to this process is if nitrogen happens to be high when peanut is planted, either through residual nitrogen left from the previous crop or if nitrogen is added to peanut directly. When nitrogen is high, this tends to decrease the symbiosis with Rhizobia, and thus the formation of nodules.

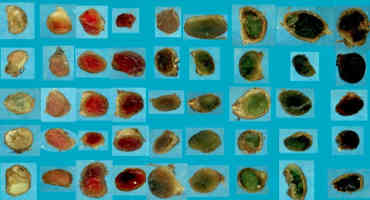

Current research at the University of Florida (UF/IFAS) is looking at this nodulation process closely, characterizing the different stages of development that nodules pass through. This knowledge may help growers better gauge how the symbiosis between peanut and the bacteria is progressing during the season, as well as estimate the stress level being experienced by the crop. To do this, graduate student David Hensley in the laboratory of Dr. Diane Rowland has been studying closely how nodules initiate, grow and become active, and finally degrade through the course of a season. Using a digital, automatic color image analysis process, David is able to use scanned images of root nodules removed from peanuts to determine the total number and average size of the nodules, and by cutting the nodules open, can determine their internal color. These three traits together are indicative of how effective the symbiosis is between the peanut and Rhizobia and how well the process of fixing nitrogen from the atmosphere is progressing.

The internal color of the nodule dictates its activity level. Nodules which are deep red in color are active, indicating that conditions are optimal for Rhizobia to perform their nitrogen-fixing function. Nodules with lighter, whitish internal color do not yet (or possibly never will) have active Rhizobia, and greenish nodules have begun to naturally age and will cease to fix nitrogen. Dark, blackish nodules, on the other hand, have begun to decay due to damage or possibly stress. By assessing the relative presence of these colors, the effectiveness of the root nodules can be determined at any point during the growing season.