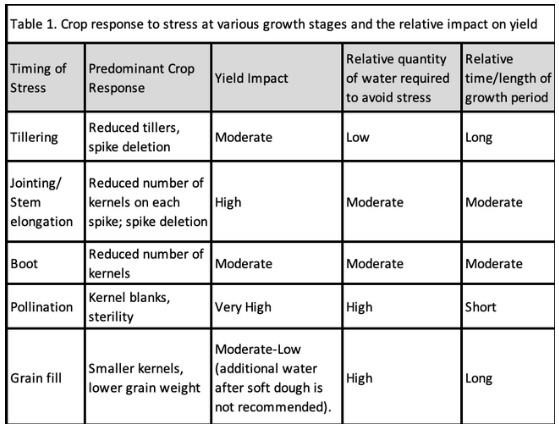

Each crop growth stage varies somewhat with respect to water-stress vulnerability. For example, the jointing stage occurs very rapidly, and the impact of stress can accumulate quickly. Meanwhile, the grain filling stage occurs over a much longer period of time. Therefore, the relative amount of water required to prevent stress earlier in the season is less than is required to prevent stress later in the season. Monitoring soil moisture prior to sensitive growth stages like jointing and pollination can prevent rapid reductions in yield potential.

Table 1: Yield Reduction Potential and Water Relations of Wheat Growth Stages

Growers without access to irrigation can also use these principles to better estimate their final yields and adjust management accordingly. For example, if the crop is severely stressed throughout the tillering and/or jointing phase, growers might consider reducing their in-season nitrogen applications to account for a reduced yield potential.

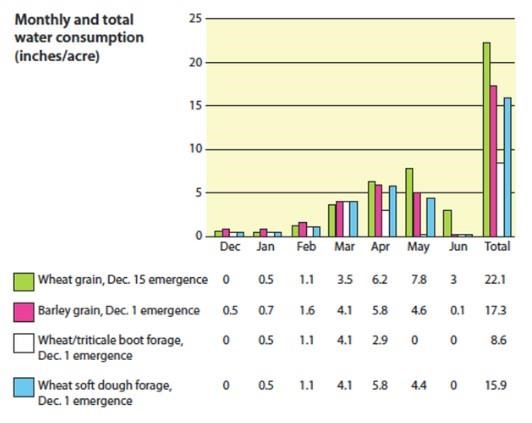

Average Water Use Throughout the Season

The seasonal wheat crop evapotranspiration, or ETc (the combination of water loss from the soil surface and water usage by the crop) averages 22 in./acre. But this amount varies greatly depending on the level of production. ETc can range from 12 to 30 in./acre depending on the yield potential of the crop, which ranges from 2000-9000 lb/acre throughout the state.

Crop water use is driven by solar energy and the growth and development of the crop canopy, both of which increase throughout California's wheat-growing season. Thus, the monthly crop water use increases rapidly in March through May. By June, grain is mostly mature, and the canopy is reduced by senescence as the plants enter the dry-down phase (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Historical average water consumption by irrigated small grains. Note that the water demand of fields can vary dramatically depending on crop yield potential.

Mitigating losses in a drought year

Under ideal circumstances, a grower would apply slightly more water than ETc to account for irrigation application inefficiency and any leaching requirement. In dry years, when access to water is limited, growers may need to pinpoint when to use water to maximize its utility. For wheat, there are several key recommendations listed below.

Growth Stage-Based Approach

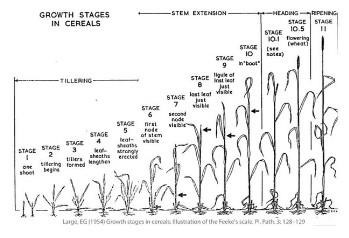

Understanding the growth stages of wheat can help growers monitor their crop and anticipate important management decisions in the season.

Figure 2: Feekes Scale Cereal Growth Stages

- Don't wait too long to apply water: Early growth stages do not require a lot of water because the crop canopy is small and the weather is typically cooler. But moisture stress during this time can severely reduce yields even if rainfall increases later in the growing season (by reducing the overall yield potential of the crop). Further, irrigation that is (moderately) in excess of crop water demand at this period of growth may not be wasted because the crop may be able to access and utilize this water as its root system expands. In a low rainfall year, a small amount of water at tillering can keep yield potential high in case the season shifts in a favorable direction later in the year.

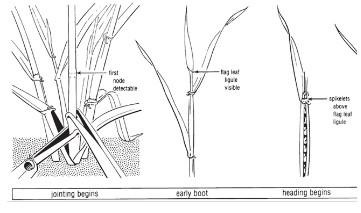

- Don't neglect the rapid growth phase (jointing): Plant reactions to stress in the jointing phase are similar to those in the tillering phase, but the canopy has expanded and ETc has increased. The plant is developing faster, and moisture stress can rapidly reduce yield potential in a relatively short period of time.

Figure 3: Jointing and Early Boot Stages Wheat

Avoid stress at pollination/flowering: Stress during pollination severely affects yield. It will impact crops with higher yield potential more than crops with low yield potential. If the crop has already experienced significant stress earlier in the season, this impact becomes less pronounced. It is more beneficial to irrigate just prior to pollination than during later stages of grain filling.

- Don't waste water later in the season: Irrigation has little to no effect on yield outcomes after the soft dough stage and late-season irrigation can lead to increased lodging. Making sure that the crop has enough water to carry it through grain fill is important to maximizing yield potential. But it is better to err on the early end of the grain fill stage versus the later end.

Table 2: Estimated timing of growth stages throughout growing regions in California. Note that environmental conditions can alter these time periods somewhat and knowing how to identify growth stages can be useful when making management decisions.

Plant and Soil Water-Based Approaches

Figure 4: Drought Stressed Wheat, note the spikey appearance of the flag leaf and the premature senescence at the base of the plant (photo: Aaron Earlea)

Monitor plants for signs of stress: Keeping track of ETc and available soil moisture will give growers a good idea of when they need to irrigate, but it's important to keep an eye out for signs of stress. Yield potential will already be lower once water stress is visible in the plant, but applying water will reduce further losses to yield potential later in the season. Catching water stress in more drought-prone parts of the field provides an early warning sign for the rest of the field. Knowing where these areas are can help growers see signs of stress in more vulnerable plants first, before symptoms become more widespread. Patterns will begin to emerge based on changes in soil type or topography. In individual plants, stress will cause leaves to progressively turn dark blue-green, wrinkle at the margins, cup or roll slightly, curl dramatically, and eventually senesce entirely. Later in the growth cycle stress will cause stunted stems, smaller heads, and blanks.

- Irrigate when plants have used 40-50% of plant available water: Stress increases as available soil moisture drops below 50%. Plants respond to water stress by slowing transpiration which in turn slows photosynthesis. This slowdown reduces yield potential. Shorter, more frequent irrigations (irrigating at 35% depletion) have been shown to increase yields in arid environments where rainfall is scarce and soil moisture depletion occurs rapidly on a daily basis. This strategy is useful when local conditions in California are particularly dry, hot and/or windy, but it should be avoided in the late stages of grain fill because it can lead to lodging. In an ideal scenario, the crop would have enough water in the root zone to carry it through grain fill by the beginning of the grain fill phase. Remember to account for the irrigation efficiency of the system. Depending on soil, water quality, and the water delivery system, irrigation efficiency typically ranges between 50-90%.

Figure 5: Blanks in drought stressed wheat.

Water Balance Irrigation Method: The Water Balance Irrigation Method is a way of accounting for plant available moisture. Soil moisture holding capacity is used as a 'bank' into which rain / irrigation events are added and evapotranspirative losses are subtracted. These numbers can help growers anticipate future irrigation events or estimate stress. There are many resources available to help growers calculate how much water they have in the soil and anticipate their next irrigation event. CDFA's Irrigation and Nitrogen Management Trainings offer valuable training with question-and-answer opportunities, their website also includes a series of videos under the “Self-Study Continuing Education” drop-down menu that provide video examples of irrigation plans for various crops. The East San Joaquin Valley Water Quality Coalition is hosting a video that provides an overview of basic principles in irrigation management using the water balance, or accounting, method. More in-depth resources that work through the process to determining things like a Maximum Allowable Depletion (MAD), irrigation set planning, and establishing root zone water holding capacity can be found here, here, and here. Growers, farm managers, and CCAs can always reach out to local Farm Advisors with questions regarding irrigation management. UC small grains expert contacts can be found here: http://smallgrains.ucanr.edu/.

Summary

There are several critical time periods during which drought stress has a larger than average impact on crop productivity. Likewise, there are different management strategies which growers can use to minimize negative impacts on yield due to drought stress. If irrigating based on crop growth stage, a good overall strategy is to meet the crop's water use requirements during the early vegetative growth stages and again at flowering. The early growth stages normally require less water and have a significant impact on productivity, and stress at flowering had disproportionately negative impacts on yield. If a plant and soil water-based approach to irrigation is used, plan to irrigate when plants have used 40-50% of plant available water and, ideally, before signs of stress are observed in the field. Finally, UCCE Advisors are available to assist with questions related to irrigation management.

Figure 6: Patchy patterns caused by drought stress and variations in soil. Knowing where textural changes occur in a field can help catch symptoms of stress early

Source : ucanr.edu