By Michelle Leinfelder-Miles

A consultant recently brought in some alfalfa plants to get another opinion on why growth was resuming slowly this spring. The field is located in Merced County and is a sandy loam soil. The field is in its fifth year, is glyphosate-tolerant, and has traditionally produced high-quality hay. About 5 acres of a 40-acre field are affected.

There are many reasons why growth may resume slowly this spring. The obvious reason, of course, is that we received a lot of rain this winter. With that rain has come associated problems from cool, anoxic (lack of oxygen) soil conditions. A previous blog article describes things to look for in alfalfa fields where there was standing water this winter, and how to diagnose problems as the weather warms and soil dries out. In this particular example, the consultant assessed soil conditions by augering down about four feet. He did not observe excessive moisture, even down to four feet, and generally, we would presume fairly good drainage from a sandy loam soil. He also sent samples to the lab for chemical analysis. The soil analysis indicated an acceptable pH (7.6), low salinity (EC 0.5-0.8 dS/m), adequate soil phosphorus (12 ppm), and marginal to low potassium (45 ppm). Despite the low potassium, no potassium deficiency symptoms have been observed on the leaves. The grower applied turkey manure to the field in the fall but did not have it analyzed, so we do not know its fertility characteristics. Additionally, the grower applied herbicides in the fall. There has been some concern that the affected acreage is reacting poorly to the herbicides; however, when herbicide damage has occurred, we would generally expect to see the damage over the entire treated acreage, and that is not the case in this field.

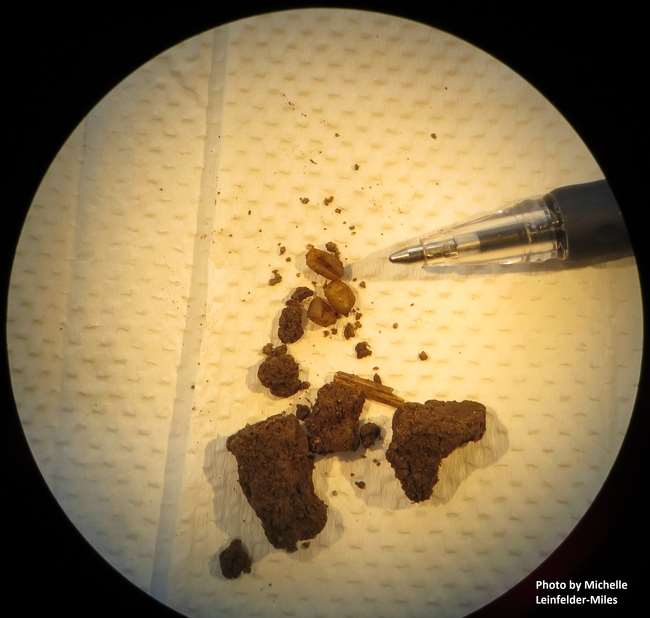

In addition to providing me with plant samples, the consultant also provided me with a small container of what he could only assume were little grubs. He wondered if these grubs were feeding on the roots and contributing to the slow spring growth. I took a look at these “grubs” under the dissecting microscope (Fig. 1), and found that they were not grubs, but rather, earthworm cocoons. I am by no means an earthworm expert, but as a graduate student, I investigated earthworms as a biological indicator of soil health in orchard systems. What is seen in Figure 1 are three soft, white (albeit dirty) cocoons. Over time, these would turn brown and have a tougher exterior which resists desiccation. Depending on the species and soil temperature and moisture conditions, earthworms may hatch in as few as three weeks and as many as five months. More information on the earthworm life cycle is available from the UC IPM webpage.

Earthworms do not feed on roots, but rather, ingest the soil and its microorganisms, mixing the soil as they feed. A recent California Agriculture article discusses how soil biodiversity contributes to soil health, defined as soil functionality. Earthworms certainly are a component of soil biodiversity, and their presence often relates to beneficial soil physical and chemical characteristics. While the jury is still out on what might be causing the slow spring growth of this alfalfa field, I think we can rule out these little, white orbs.

Source:ucanr.edu