Figure 4. Normalized Difference Red Edge Index (NDRE) indicates the plant vigor (growth) in February-irrigated (blue) and non-irrigated (red) plots.

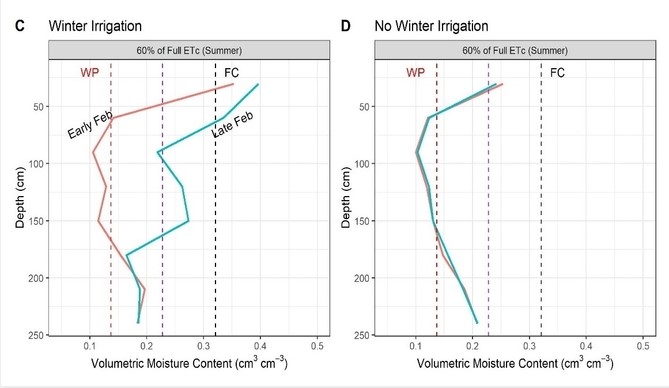

Soil Moisture Changes. Difference in water status between winter irrigated plots and no-winter irrigated plots in the Davis trial showed very dry conditions in early February (Figures 5 and 6). In plots that were relatively well-watered in 2020 (Figure 5), a single irrigation was sufficient to bring many parts of the subsoil back to a full profile (Figure 5A), while plots with no winter irrigation continued to dry down (Figure 5B). In plots that were stressed in 2020, it was more difficult to fill the profile, and lack of winter irrigation had a severe effect on soil moisture (Figure 6).

Figure 5. In plots that received 100% of their ET in 2020, a single irrigation in early February resulted in filling the profile (5A). However, without winter irrigation (5B), the sub-soil continued to dry down. Winter rains only impacted the top 12” of the soil profile. (Davis, CA).

Figure 6. A February watering partially filled the top part of the profile (6C) of previously stressed plots, but not as successfully as Figure 5A. Without winter irrigation, the subsoil continued to remain very dry through late February (6D) in previously stressed plots. (Davis, CA).

RE-WATERING/WINTER FLOODING STUDIES (Fresno County)

At the University of California Research and Extension Center (Parlier, CA), in Fresno County, an experiment was conducted to examine the effects of winter flood irrigation on growth and yield of alfalfa. While this was designed for winter recharge of aquifers, it gave us an opportunity to understand the effects of winter watering on alfalfa growth. In this case, we also had late-summer deficit irrigation treatments in the previous year. In 2019-20, we found that winter irrigation increase yield during that production year, particularly in the first three harvest periods, both in plots that were deficit irrigated and those that had received full irrigation the previous year (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Effect of winter flood irrigation on 2020 alfalfa yields that were either fully irrigated or deficit irrigated in 2019. UC Kearney Research and Extension Center, Parlier, CA.

GROWER EXPERIENCES

In many parts of California and other Western States, winter rains are almost always insufficient to allow vigorous regrowth in the spring. In Buttonwillow (near Bakersfield), average rainfall is about 7”/year, almost all between November and March. Therefore, many growers understand the value of these winter water applications. On a drip irrigated field in Buttonwillow, CA, the growers have flood irrigated this field in February of 2020, even though it will be drip -irrigated for most of the year. They do this because 1) it fills the soil profile early, and 2) flood irrigation assists in controlling gopher populations

Figure 8. Flood irrigation in February, 2020 on an (otherwise) drip irrigated field in Buttonwillow, CA. This grower flood irrigates 2x per year, but uses drip irrigation for most of the year.

CONCLUSIONS

In our view, in a dry spring period, fill that profile early!! We believe that it is not only beneficial to the first growth period, but also likely to be helpful in mid-summer as well. The highest yielding and highest quality production is in the first several cuttings of the year. Late cuttings of alfalfa are typically 50-60-% the yields of those first cuttings. Therefore, in a drought year, it's important to water early, to fill the profile, maximize production during the early period. Probe your soil! Any way to estimate profiles soil moisture would be help even with simple time-tested technologies like steel soil probe and 'look and feel' for soil moisture. If one has to stop irrigating in mid-summer due to lack of water, the early growth will make up for the lack of production later. Once you're behind, it's hard to catch up.

Source : ucanr.edu