By Rory Lewandowski

As corn harvest continues across our area, I have received a few questions about corn ear rots and mycotoxins. Across the state, particularly from the central part and west there have been lots of reports of diplodia ear rot. In recent weeks, Pierce Paul, OSU Extension Corn and Wheat Extension Pathologist has received corn samples with Trichoderma, Fusarium and Gibberella ear rots. In response to samples he has received as well as questions from growers, Pierce wrote an excellent article for the OSU Extension CORN newsletter on ear rot identification, quantification and testing for mycotoxins.

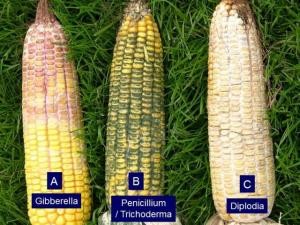

Ear rots differ from each other in terms of the damage they cause (their symptoms), the toxins they produce, and the specific conditions under which they develop. So, a good way to determine whether you do have a major ear rot problem this year is to quantify the disease in your field and get suspect samples tested for mycotoxins. And the best way to tell the difference among the ear rots is to know the types of symptoms they produce.

TRICHODERMA EAR ROT – Abundant thick greenish mold growing on and between the kernels make Trichoderma ear rot very easy to distinguish from Diplodia, Fusarium, and Gibberella ear rots. However, other greenish ear rots such as Cladosporium, Penicillium and Aspergillus may sometimes be mistaken for Trichoderma ear rot. Like several of the other ear rots, diseased ears are commonly associated with bird, insect, or other types of damage. Another very characteristic feature of Trichoderma ear rots is sprouting (premature germination of the grain on the ear in the field). Although some species of Trichoderma may produce mycotoxins, these toxins are usually not found in Trichoderma-affected ears under our growing conditions.

DIPLODIA EAR ROT – Diplodia causes a thick white mass of mold to grow on the ear, usually initiating from the base of the ear and growing toward the tip. Eventually the white mold changes to a grayish-brown growth and infected kernels appear glued to the husk. Infected ears are usually lightweight and of poor nutritional value. When infections occur early, the entire ear may become moldy. When infections occur late, only a fine web of fungal growth appears on and between the kernels.

GIBBERELLA EAR ROT – When natural early-season infections occur via the silk, Gibberella ear rot typically develops as white to pink mold covering the ear tip to the upper half of the ear. However, infections may also occur at the base of the ear, causing the whitish-pink diseased kernels to develop from the base of the ear upwards. This is particularly true if ears dry-down in an upright position and it rains during the weeks leading up to harvest. The Gibberella ear rot fungus may also infect via wounds made by birds or insects, which leads to the mold developing wherever the damage occurs. When severe, Gibberella ear rot is a major concern because the fungus produces several mycotoxins, including deoxynivalenol (vomitoxin), that are harmful to livestock. Once the ear is infected by the fungus, these mycotoxins may be present even if no visual symptoms of the disease are detected. Hogs are particularly sensitive to vomitoxin. Therefore the FDA advisory level for vomitoxin in corn to be fed to hogs is 5 ppm and this is not to exceed 20% of the diet. For ruminating beef cattle and feedlot cattle the advisory level is 10 ppm and not to exceed 50% of the diet and for dairy cattle dietary levels of 300 to 500 ppb DON (0.3 to 0.5 ppm) in dairy feeds indicate mycotoxin problems and warrant attention.

FUSARIUM EAR ROT. Fusarium ear rot is especially common in fields with bird or insect damage to the ears. Affected ears usually have infected kernels scattered over the ear among healthy-looking kernels or are confined to kernels that are damaged. The fungus appears as a white mold and infected kernels sometimes develop a brown discoloration with light colored streaks. Several different Fusarium species are involved with Fusarium ear rot. One common species produces a toxin called Fumonisin. Horses are particularly sensitive to Fumonisin, but cattle and sheep are relatively insensitive.