The 2021 Rent in Historical Context

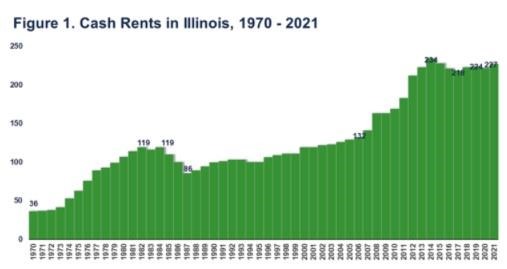

At the beginning of August, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) released estimates of state-level cash rents. Cash rents in Illinois were estimated to average $227 per acre, up by $5 per acre from the 2020 level of $222 per acre (see Figure 1). The 2021 rent is the third-highest since 1970, below the all-time high of $234 per acre set in 2013 and $228 per acre rent in 2014.

Cash rents have exhibited variability over time. Cash rents were $36 per acre in 1970, rising in a continuing pattern to highs in 1982 and 1984 when cash rents averaged $119 per acre (see Figure 1). Cash rents then fell from the 1984 high to $86 per acre in 1987, a decrease of 28% from the 1984 high. Note that U.S. agriculture experienced a severe financial crisis during the mid-1980s.

During the period from 1987 to 2006, cash rents increased an average of $2 per year, reaching $132 per acre in 2006. From 2006 to 2013, cash rents rose much faster, averaging a $13 per year increase, reaching a high of $234 in 2014. From 2006 to 2013, relative prosperity existed in agriculture, spurred by growth in corn use for ethanol production, growth in soybean exports, and yield shortfalls below trend in several years.

Corn and soybean prices then declined, followed by a reduction and leveling off in average cash rent levels. Cash rents decreased from $234 per acre in 2013 to $218 in 2017. Average Illinois cash rents were $223 per acre in 2018, $224 in 2019, $222 in 2020, and $227 per acre in 2021.

Cash Rents Relationship with Agricultural Returns

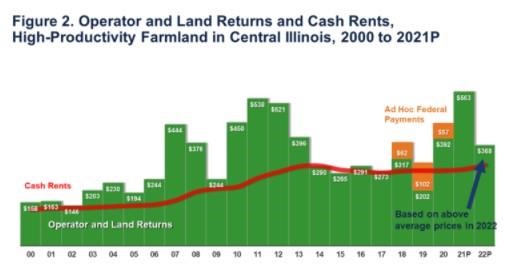

Movements in cash rents generally follow agricultural returns, typically with cash rents lagging changes in returns. This lagged relationship can be seen in Figure 2 for high-productivity farmland in central Illinois. Figure 2 shows average cash rents for central Illinois farmland, which exhibit the same time patterns as state-level cash rents but typically at a higher level. In 2020, for example, the average cash rent for high-productivity farmland in central Illinois was $275 per acre, $53 per acre higher than the $222 per acre cash rent for Illinois. Central Illinois has higher productivity farmland than the state as a whole.

Figure 2 also shows operator and land returns, which equal gross revenue minus non-land costs. Operator and land return show in Figure 2 are for a 50% corn and 50% soybean rotation, and represent a return to both the farmer and landowner. If the farmland is cash rented, subtracting the cash rent from the operator and land return gives the farmer return. Over time, cash rents and lagged returns have closely followed each other, having a .72 correlation coefficient. In 2021, the operator and land return is projected at $463 per acre and the average cash rent at $280 per acre, leaving a farmer return at $183 per acre.

From 2000 to 2006, operator and land returns were typically above cash rents, and cash rents rose moderately during this period. Higher returns persisted from 2005 to 2012, and cash rents rose at a relatively rapid rate. From 2013 to 2017, operator and land returns were much lower. As a result, cash rents declined during this period but average cash rents remained higher than returns in 2014, 2015, and 2017.

Operator and land returns were above average cash rents in 2020. Projections are for above-trend yields and relatively high prices in 2021, leading to projected returns being above cash rents in 2021.

Implications for 2022

Recent return projections for 2022 indicate operator and land returns are at $328 per acre for a 50-50 corn-soybean rotation in Central Illinois on high productivity farmland, above average cash rents. Overall, the relatively higher return in 2020 and 2021, along with higher projected returns in 2022, could lead to upward pressures on cash rents.

The danger of setting cash rents at higher levels revolves around prices used in making 2022 projections. For 2022, projected prices are $4.50 per bushel for corn and $12.35 per bushel for soybeans, well above the average price levels from 2014 to 2019 of $3.66 per bushel for corn and $9.91 per bushel for soybeans. If prices remain at the higher projected levels, operator and land returns for a rotation will likely remain above the average cash rents even with some cash rent increases. In addition to potentially higher land costs, the expectation for record high non-land costs is putting pressure on 2022 returns. A return to the 2014-2019 average price levels would push operator and land returns below average cash rents, leading to negative returns for farmers (see farmdoc daily, August 10, 2021).

Summary

Overall, higher agricultural returns in recent years likely led to rising rents in 2021. As long as prices remain at or above the higher prices projected for 2022, positive returns to farmers are possible. However, a return to 2014-2019 price levels in the 2022 budgets would lead to negative farmer returns, particularly given the large non-land cost increases projected. These uncertainties suggest using a rental agreement with payments contingent on economic outcomes, such as a variable cash rent (see farmdoc daily, August 10, 2021) or a share rent arrangement.

Source : illinois.edu