Many producers prefer to purchase bucks born and raised as twins. photo by Diane Fisher

Weaning weight: Many kids in the northeast are sold at weaning, so heavier weaning weights can increase the profitability of an operation. A good goal is to have meat goat kids weigh 35 to 50 pounds or more by 90 days of age. However, this is not a realistic goal for all breeds.

Kids born as singles normally weigh more at weaning than kids born as twins or triplets. Other factors, such as the sex of the kid and the age at weaning, also influence the weaning weight. Keep in mind that a pair of twins will most likely weigh more at weaning than the single kid. Thus, the weight of the pair, even if its individuals weigh less than the single born kids, determine the income produced by the doe.

Adjusting Weaning Weights

As alluded to earlier, animal performance is based both on genetics and the environment. Producers can adjust weaning weights in order to compare individual kids born on the same farm, since these animals have theoretically all been exposed to the same environmental conditions.

Weaning weights can be adjusted for:

- age at weaning

- birth type (single, twin, or triplet)

- rearing type (single, twin, or triplet)

- sex of the kid

- age of the dam or mother

To adjust for the age at weaning:

- Determine an age to adjust to. Weaning weights are typically adjusted to 90 days of age but could also be adjusted to other ages such as 60 or 120 days of age.

- Subtract the birth weight from the weaning weight. This is the weight gained.

- Divide by the age of the kid (in days) when it was weighed. This is the average daily gain.

- Multiply the average daily gain by the weaning age you are adjusting to (usually 90 days).

- Add the birth weight.

Estimated 90-day weight = (((weaning weight – birth weight)/age at weaning) X 90) + birth weight.

The estimated 90-day weight can then be adjusted for more factors. The following table lists adjustment factors to account for the age of the doe, sex of the kid, birth type, and rearing type.

The tables below are adapted from the Breeding and Selection Chapter of the Sheep Production Handbook produced by the American Sheep Industry Association, Inc. (This handbook can be purchased through the American Sheep Industry Association and through select sheep supply companies.)

Kid Preweaning and Weaning Weight Adjustment Factors

| Item to be adjusted | Class | Adjustment Factor |

|---|

| Doe Age in Years | 1 | 1.10 |

| Doe Age in Years | 2 | 1.09 |

| Doe Age in Years | 3+ | 1.00 |

| Sex | Buck | 1.00 |

| Sex | Wether | 1.08 |

| Sex | Doe | 1.11 |

| Type of birth and rearing* | 1/1 | 1.00 |

| Type of birth and rearing* | 1/2 | 1.14 |

| Type of birth and rearing* | 2/1 | 1.04 |

| Type of birth and rearing* | 2/2 | 1.18 |

| Type of birth and rearing* | 3/1 | 1.08 |

| Type of birth and rearing* | 3/2 | 1.23 |

| Type of birth and rearing* | 3/3 | 1.27 |

*Type of birth and rearing:

1/1 = single raised as a single

1/2 = single raised as a twin

2/1 = twin raised as a single

2/2 = twin raised as a twin

3/1 = triplet raised as a single

3/2= triplet raised as a twin

3/3 = triplet raised as a triplet

Notter, D. 2008. The 2007 Boer Goat National Genetic Evaluation. Boer Goat Improvement Network Notebook, No. 4, National Sheep Improvement Program, Centennial, CO, 15 pp.

Example of Adjusting a Weaning Weight

A twin doe kid was born on January 2nd, weaned on April 4th, and was raised as a twin. The dam is 2 years old.

- Birth weight = 7 lbs.

- Weaning weight = 45 lbs.

- Actual age at weaning = 91 days

- Weaning age to adjust to: 90 days

- Adjust the weaning weight for 90 days. Use the following formula:

- Estimated 90-day weight = (((weaning weight – birth weight)/age at weaning) X 90) + birth weight

- (((45-7)/91) X 90) + 7 = 44.58 lbs.

- Now adjust the weaning weight for doe age, sex of the kid, and the type of birth and rearing, by multiplying by the adjustment factors found in the table:

- 1.09 = adjustment factor for a 2-year-old doe

- 1.11 = adjustment factor for a doe kid

- 1.18= adjustment factor for a twin raised as a twin

44.58 lb. X 1.09 X 1.11 X 1.18 = 63.65 lb.

Therefore, the adjusted 90-day weight of this doe kid is 63.65 lbs. This calculation allows producers to better compare kids and make more informed selection decisions.

Selection Using Visual Appraisal

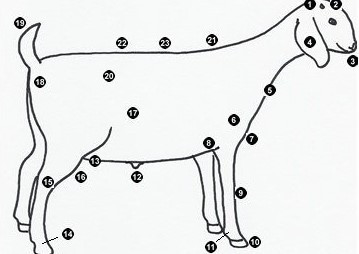

In addition to using individual performance and EBVs, anyone involved in goat production should have the skills to evaluate the physical characteristics of individual bucks for their potential as breeding stock. Producers should be able to visually evaluate goat structure and they should also be able to evaluate muscling.

In order for a buck to be sound on his feet and legs, he must be structurally correct. Correct structure enables the buck to move properly and proper movement allows bucks to comfortably mount does during breeding.

To be able to evaluate or select structurally correct bucks, producers must first have an understanding of the parts of a goat as well as each part’s correct structure. Remember, selection should begin with a look at performance records followed by visual evaluation. Visual appraisal can be a good indicator of frame size, muscling, body structure, feet and leg structure, and breed character.

Correct skeletal structure is important and essential for any animal to move to feed and water. This structure can be observed in shoulder angle, pastern angle and levelness of the hips and top line from neck to rump. The angle of the shoulder should be approximately 45 degrees, while the pastern angle should be approximately 50 to 55 degrees or slightly more. Skeletal angles in the shoulders, hips and legs are all important for ease of movement. When angles are within appropriate ranges, the animal is generally level across their topline and able to move freely.

When making visual selection decisions for correct structure, it is important to know all the external parts of a sheep. Each part has an ideal characteristic for breeding bucks.

- Poll

- Forehead

- Muzzle

- Ear

- Dewlap

- Point of shoulder

- Brisket

- Point of elbow

- Knee

- Hoof

- Dewclaw

- Sheath

- Flank

- Pastern

- Hock

- Stifle

- Barrel

- Pin bone

- Tail

- Hip

- Withers

- Loin

- Back

An ideal breeding buck should have certain physical characteristics. These include

- a long, square, level rump,

- well-muscled leg

- adequate diameter of cannon bone,

- a long, wide loin, deep loin,

- level top,

- well-sprung ribs, or in other words a round rib cage with large volume

- a deep forerib,

- smooth shoulders,

- a masculine neck and head,

- a trim neat dewlap and breast,

- strong upright pasterns, and

- Adequate and evenly sized testicles

- And the feet and legs should be placed directly underneath the animal

Producers should select bucks that possess correct structure as well as other visual characteristics and good performance data.

There are a number of undesirable feet and leg characteristics that animals can exhibit. As you evaluate animals, you should be aware of these issues:

Pigeon toed: An animal is pigeon toed or toed-in if when viewed from the front, the toes turn towards each other rather than pointing straight forward.

Bowlegged: An animal is bowlegged if when viewed from the front, the knees curve out away from each other or if viewed from the rear, the hocks curve out away from each other.

Splayfooted or toed-out: An animal is splayfooted or toed-out if when viewed from the front, the toes turn out away from each other rather than pointing straight forward.

Knock-kneed: An animal is knock-kneed if when viewed from the front, the knees lean toward each other and are not in a straight line with the legs.

Cow hocked: An animal is cow hocked if when viewing the hind legs from the rear, the hocks, which are the hind leg joints, are turned inward or are placed too close together. This causes the toes to turn outward.

Sickle hocked: An animal is sickle hocked if when viewing the rear legs from the side, the hock has too much angle or set. A line dropped perpendicular from the pin bones to the ground should lie parallel to the cannon bone. A sickle hocked animal has hocks that angle too much, which causes the animal’s feet to stand too far underneath their body. Often these animals will droop excessively from hooks to pins.

Post legged: An animal is post legged if the hock has too little angle or set. The animal is too straight through the joint, which results in a very stiff, restricted movement due to the lack of flexibility. More sheep become unsound because of being post legged than sickle hocked.

Buck kneed: An animal is buck kneed, or “over at the knees”, if the full extension of the animal’s knee cannot occur. When observed from the side, the legs appear slightly bent. This is usually seen in sheep that are too straight in the shoulder.

Calf kneed: Calf kneed is the opposite of buck kneed. This means that the animal stands “back at the knees” when viewed from the side.

Weak pasterns: Weak pasterns, which are the leg bones between the hoof and fetlock, can be determined by visually looking at their angle. Weak pasterns have more than the normal slope to them and can indicate a structural fault. As mentioned previously, correct pastern angle should be approximately 50 to 55 degrees or slightly more.

Sound hind legs are vital to the mating ability of bucks, because during mating, most of the buck’s weight is supported by the hind legs. A buck with hind leg defects may suffer pain while moving or mounting, which may interfere with his desire to mate. In an aging buck with faulty conformation, defects become more apparent and may tend to decrease their ability to breed larger groups of does.

The buck’s legs should be free of excessive swelling at any of the joints, and joint flexure should be smooth and free of locking in any position. A goat with straight hind legs, or post legs, is predisposed to swollen hocks and arthritis in the hind leg joints. A goat with post leg or sickle hocks also may have more difficulty moving earlier in life, leaving it lame or unable to move freely throughout a pasture or, in the case of bucks, to breed does.

Other visual characteristics to consider when evaluating bucks relate to how filled out the animal may appear. Bucks selected for breeding should exhibit volume and capacity. Indicators of volume are:

- Width of the chest floor, which is the lower chest between the two front legs,

- Depth of body, which is the depth from the top of the animal’s back to the bottom of their belly

- Shape of ribcage, which is the roundness of the ribcage.

- Uniformity of body depth, which refers to the animal being the same depth at the top of the shoulders to fore flank compared to the top of the hips to rear flank.

Goats with more volume are generally easier fleshing. That is, they produce external fat easily and are usually lower maintenance than goats that lack volume. Bucks should be selected with volume in mind in order to transmit these traits to offspring.

The muscling of an animal is also important to the meat animal industry. Heavily muscled animals tend to produce more meat and less fat than animals with less muscle. Consumers prefer goats with larger loin chops and with less fat. Indications of muscling can be seen over the animal’s top and in the loin area, length of the hip, width between the rear legs, and the hindquarters.

Leg structure, as well as volume, and muscling, all play a role in the correct structure of goats. Structure helps determine how well an animal will function. It can also impact the longevity of an animal in the herd. So, it is important to consider structure when selecting bucks in order to maintain a healthy and viable operation.

Buck Cost Considerations

The final consideration in buck selection, but often the starting point for many producers, is the price. How much can the operation afford to pay for a buck? This not only depends on a bank account but should also depend on the value of that buck to the operation. So, how does the operation determine what is appropriate?

Purchasing a new buck should always require careful consideration in all areas, including cost. All producers want to find a bargain: the highest quality genetics for a bargain price. However, progressive producers should spend some time developing a selection strategy and setting up a budget to determine what a buck is worth to the operation. Consider the buck an investment and think about what value that buck will bring to the operation.

When looking at a buck as an investment an item to consider would be how he can be expected to impact improved production. How will his kids compare to previous kids born on the operation? Will they have heavier weaning weights? Will they be more acceptable to buyers? What traits will his daughters exhibit to improve performance? These are all considerations that not only impact the bottom line the first year after this buck produces kids, but into the future as daughters retained in the herd.

The value that a buck’s daughters bring to a herd should be considered in addition to performance and visual characteristics when considering a price to pay for a buck.

When considering the cost of a new buck, begin by estimating the salvage value of the buck once the operation has finished using him. If the operation has a market for aged bucks, how much should the operation charge? If selling aged bucks are there any health tests that should be performed to ensure the buyer that the buck won’t share any diseases with the new herd? Subtract those costs to arrive at a salvage value. If the buck sells through a sale barn, what is the likely value for cull bucks? Or will the salvage value be zero because the buck can be expected to live the rest of his life at this operation?

Consider an example of a producer paying $1,500 for a buck that will be used for 2 years to service 35 does each year. After the producer finishes using this buck, he intends to sell him through a sale barn for about $200. This makes the difference between the purchase price and the salvage value $1,300. By dividing the salvage value by the 2 years the producer plans to use the buck, the depreciation cost amounts to $650 annually. Divide the annual depreciation cost of $650 by the number of does serviced to determine the depreciation per doe, which would be $18.57 for this example. Another option would be to divide this by the average value of the kids sold, to arrive at the pounds of kid each doe must produce each year in order to cover the cost of buck depreciation. Calculate this by dividing $18.57 by the sale price of the kids. A value of $3.50 per pound for kids sold at weaning in the Eastern United States would mean that 5.3 lbs. produced by each doe would cover the cost of buck depreciation.

An operation must know the cost of production to determine if this is acceptable. What does it cost the operation to keep a doe per year? If $18.57 is added to a doe’s annual costs, how will this impact the operation’s profitability? Should this cost be considered an investment for the future when this buck’s daughters enter the herd?

Another way to look at the salvage value of the buck is to consider how many kids per year must be sold to cover the depreciation cost. For example, an operation sells 60 lb. kids for $250. Subtract sales and transportation costs. For this example, $225 is the value that a kid brings to the operation. Therefore, $650 divided by $225/kid means that it takes about three kids each year to cover the cost of the buck.

Producers should always purchase the best buck that they can afford. A buck has the potential to impact a herd for many years through his daughters. So, spend some time determining what traits a buck should possess to improve the operation, what value a buck will have to the operation, and then decide on a fair price.

Summary

Every meat goat operation should spend time developing a buck selection strategy. Analyzing the doe herd will help to determine what traits would be important in a buck. Producers should also consider performance data, either in the form of EBVs or adjusted weaning weights, in addition to visually appraising the buck. Be willing to pay a fair price for a good buck. Developing a good strategy will yield bucks that produce kids that perform well and future daughters that improve genetics within the herd while maintaining operation profitability.

Source : psu.edu