By Doug Mayo

Cashing in on Cover Crops

The University of Georgia recently released a well written publication,

UGA Baleage Production and Use that discusses key recommendations for success, as well as advantages and challenges of baleage as compared to dry hay production. After reading through the publication, I was reminded of an often overlooked opportunity to utilize idle crop land to produce high quality forage for grazing or baleage for beef or dairy cattle. Much has been shared over the years through articles in Panhandle Ag e-News on the value of

cover crops, but what has not been discussed as thoroughly is the opportunity to turn these cover crops into animal gains for additional income for crop farms. One of the great efforts of the long and fruitful career of

Dr. David Wright, UF/IFAS Agronomy Specialist, and his associates, has been incorporating bahiagrass into a

Sod-Based Crop Rotation that includes cattle grazing in a rotation with peanut and cotton production. Through this project, the research team has decades of data that prove the benefits of incorporating grazed forages into a crop-focused farm operation. But what if you don’t want invest in the cattle, fencing, or labor needed to add cattle to a crop-focused operation? There is a real opportunity to produce income from small grain cover crops managed for livestock feed as round bale silage aka baleage. The challenge comes with how to get the forage from the crop field to the livestock, and how to make the necessary agreement between producer and buyer.

Why Cool-Season Forages?

Annual forages, in general, are fast growing crops, with less indigestible fiber (ADF) than perennial grasses such as bahiagrass or Bermudagrass. Most annual crops are grown for 90-120 days and then end with seed production. They are more expensive to produce, because of the need to prepare land and plant seed for each growing season. There is also a transition time between crops, so perennial grass pastures have a real advantage for grazing. But the quality of annual crops is excellent, because they are more digestible; so if they are harvested before maturity, the nutritional value is really high.

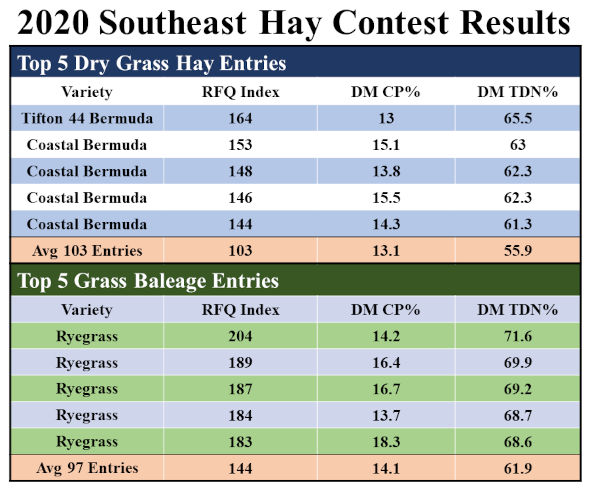

There is potential to grow cool-season cover crops that are harvested as high quality forage. The chart below shares the top five entries and category averages comparing dry grass hay to grass baleage in the 2020 Southeast Hay Contest. These were entries the very best grass hay and baleage produced last year. While there is not that much variation in the top five of the two categories, the category averages tell the real story. The balage samples had a 6% advantage in energy (Total Digestible Nutrients or TDN), and a 40% advantage in the fiber digestibility (Relative Forage Quality or RFQ).

The bahiagrass that is used for two years in a sod-based rotation system certainly offers major benefits for the cash crops that follow it by limiting the impact of diseases, nematodes, and other pests that develop in a continuous crop rotation. While two years of grass offers the greatest response from the following cash crops, cover crops in the off-season can also offer benefit to the soil health and the warm-season crops that follow. Small grains such as rye and oat make excellent cover crops, but these same crops can also be managed to produce high quality forage.

Many livestock operations dedicate land for winter grazing of small grains and ryegrass, but for most operations only a small percentage of their land is utilized this way, because of the need for perennial pastures. While grazing is the lowest cost, most efficient system for harvesting forage crops, there is an opportunity to preserve cover crops for use throughout the year as baleage. Because baleage is rolled and immediately wrapped at a high moisture content (55-65%) it is a better fit with the short, cool days associated with early-mid spring harvest than traditional dry hay. While these forages can certainly be preserved as dry hay, the extended drying time required is usually not available until late-April through mid-May. This later harvest window does not fit well with traditional crop operations, that need to be planting corn, cotton, and peanuts at that same time of year. This is also generally when the forage crops are nearing maturity, and not at the peak nutritional value. If grazing cover crops is not feasible, harvesting them as baleage is the next best option.

Because baleage is rolled/wrapped at a high moisture content (55-65%) it is a better fit with the short, cool days associated with early-mid spring harvest than traditional dry hay. In-line baleage wrapper demonstration at the 2018 Cattlemen’s Tour in Jackson County. Credit: Doug Mayo, UF/IFAS

Challenges with Baleage

Hopefully, I have at least peaked your interest and have you considering this option for crop field utilization over the winter. However, there are some real challenges to making this system work. The biggest challenge is the cost of the equipment to harvest and preserve baleage. According to

UGA Baleage Production and Use, bale wrappers range from $18-40K, balers capable of handling high moisture forages are around $5k more expensive than conventional hay balers, and the plastic adds $5-10/ton as compared to traditional hay harvest costs. The other sizeable challenge is storing and hauling this high moisture feed to the herd to be fed. If there is a cattle herd on the same farm as a crop field, this may not be a major issue, but if it is miles down the road this could add extra labor and transportation costs. The baleage bales must stay wrapped until fed, so it is best to wrap the bales where they will be stored for feeding. At the storage site, unwrapped bales should be fed within two days after being exposed to the air or they will spoil. A final challenge is that generally cover crops are not managed with the same intensity as they would be for forage production. Cover crops typically are planted at a much lower seeding rate, with minimal fertilizer applied. If you are producing forage from crop fields for your animals, all of this makes good sense, if the herd is large enough to overcome the added costs. If you have to sell the baleage, you are going to have to make prearranged agreements with buyers. The bales must be wrapped in the place where they will be stored, as soon as possible to prevent spoilage. This system would not work well to sell a few bales at a time to random buyers. You have to have a total plan in place before harvest begins.

Take Home Message

Cool-season annual forages (small grains and ryegrass) are the grasses with the highest level of nutrition we can grow in the Southeast. Some of these forages (not ryegrass) have also proven to be excellent cover crops in rotational cropping systems. So, there is an opportunity to ramp up the management of these cover crops to make high quality feed for livestock. But like most other farming ventures, you have to develop the system to make it work out profitably. There is an opportunity to add income from highly productive crop fields over the winter with livestock grazing, or for producing baleage from cool-season forages. If you are already planting cover crops, the main increase in management comes with two baleage harvests, transportation, and wrapping. In the end this will not work for every crop field or farm operation, so you have to decide if this concept fits well with your other interests. You may opt instead to simply go hunting, or take a vacation to enjoy the winter break and rest up before warm season crops are planted again.