A variable cash rent lease calculates cash rents based on percentages of crop revenues unless the result of those calculations is outside a range set by a minimum and maximum cash rent. The percent of crop revenue is called the rent factor. Important terms of this share rent lease are given below:

Minimum Cash Rent: A minimum cash rent is included to meet Farm Service Agency (FSA) requirements to be classified as a cash lease. FSA will treat the agreement as a share rent if a meaningful minimum rent is not in place, in which case the landowner will share in government support payments. For simplicity, both the farmer and landowner often desire for the arrangement to be treated as a cash lease.

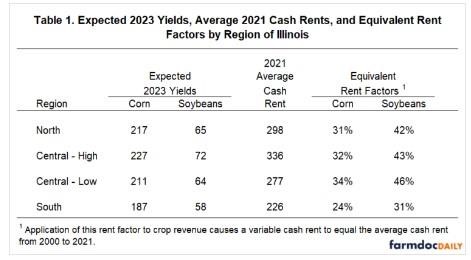

We suggest the following minimum cash rents by region of Illinois:

North (217 bushels per acre expected corn yield for 2023): $200 per acre

Central-High (227 bushels per acre expected corn yield for 2023): $230 per acre

Central-Low (211 bushels per acre expected corn yield for 2023): $180 per acre

South (187 bushels per acre expected corn yield in 2023): $130 per acre

These minimum levels are approximately $100 per acre below average 2021 cash rents for that region (see Table 1).

Maximum Cash Rent: With a minimum, the farmer is not sheltered against very low revenues. The maximum counters the impacts of the minimum, providing farmers more income in years of high revenue. The following maximums are suggested:

North (217 bushels per acre expected corn yield for 2022): $400 per acre

Central-High (227 bushels per acre expected corn yield for 2023): $430 per acre

Central-Low (211 bushels per acre expected corn yield for 2023): $380 per acre

South (187 bushels per acre expected corn yield in 2023): $330 per acre

These maximum levels are approximately $100 per acre above average 2021 cash rents for that region (see Table 1).

Crop Revenue: The cash rent will be a percent of crop revenue, with crop revenue for each crop equaling:

farm yield x market price.

Farm yield: Farm yield comes from the farm and needs to be calculated after harvest. If the grain is delivered off-farm, delivery sheets could provide yield. An agreed-upon methodology needs to be specified if on-farm storage used. Yield should be calculated at an agreed upon moisture, most likely the moisture used at the grain elevator.

Market price: Market price can be calculated using quotes from an agreed-upon delivery point, with the selected delivery point being the most likely place where grain will be delivered. We suggest using the months from March to October during the current production year. October is chosen so that cash rents can be calculated quickly after harvest. Quotes can be collected one day per week, with Wednesday being the recommended choice for the day (avoid Mondays as Memorial and Labor Day are always a Monday). Fall delivery prices are appropriate for the months from March to August. Cash prices can be used for September and October.

Rent Factor: A crop’s rent factor will be multiplied by that crop’s revenue to arrive at that crop’s cash rent level.

Table 1 shows what we refer to as equivalent rent factors. Take the 31% for corn in northern Illinois. If a 31% rent factor was used for corn from 2000 to 2020, the rent from a variable cash rent would equal the average standard cash rent over time in northern Illinois. Higher rent factors would generate a higher rent for the landowner and vice versa. If the goal is to maintain this historical relationship, we suggest the following factors:

Northern and Central Illinois: 32% for corn, 43% for soybeans.

Southern Illinois: 24% for corn, 31% for soybeans.

Rent factors are lower for corn because corn crop revenue usually is greater than soybean crop revenue.

Percent Acres in Corn and Soybeans: Lease payments will be based on a percentage of each crop grown on the farm.

Timing of payment: We suggest two payments: one in the spring and one in the fall. The spring payment could equal the minimum cash rent. The second payment of additional cash rent can occur after harvest when farm yield is known. In most cases, the latest the second payment will occur is in December.

Example of Rent for Variable Cash Rent Agreement for 2023

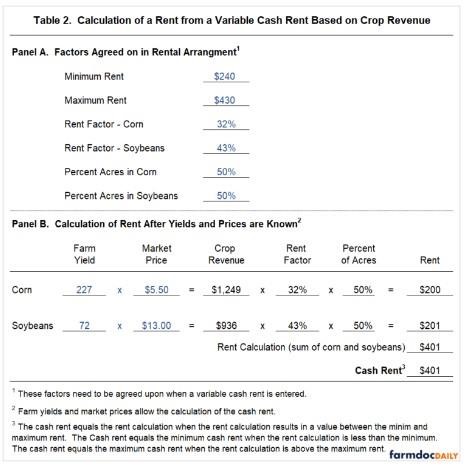

We present two cash rent payment examples using suggested parameters for high-productivity farmland in central Illinois:

Minimum cash rent: $230 per acre

Maximum cash rent: $430 per acre

Rent factor – corn: 32%

Rent factor – soybeans: 43%

Percent of acres in corn: 50%

Percent of acres in soybeans: 50%

We calculate rents for two sets of prices: 1) projected prices used in the August version of the 2023 Crop Budgets and 2) the average prices from 2014-2019. The 2023 budgets use a $5.50 price for corn while the 2014-2019 average price was $3.66. For soybeans, the 2023 planning price is $13.33 and the 2014-2019 average price is $9.54. The 2023 budget prices are much higher than 2014-2019 average prices.

2023 Budgeted Prices: Below are farm yields and market prices that come from the 2023 Crop Budgets:

Farm yield — corn: 227 bushels per acre

Farm yield — soybeans: 72 bushels per acre

Market price — corn: $5.50

Market price — soybeans: $13.00

Table 2 shows the calculation of the rent payment, with Panel A giving agreed-upon parameters and Panel B gives the calculation of the rent. Given the above yields and prices, the cash rent is $401 per acre (see Panel B of Table 2).

If, instead, prices are the 2014-2019 averages — $3.66 for corn and $9.54 for soybeans — the cash rent is $317 per acre.

Given trend yields, the maximum cash rent of $430 per acre will be reached if prices increase 7% to $5.89 per bushel for corn and $13.91 per bushel for soybeans. The minimum cash rent would be reached if prices decreased 40% to $3.30 per bushel for corn and $7.80 per bushel for soybeans.

Comparison of Rents Over Time

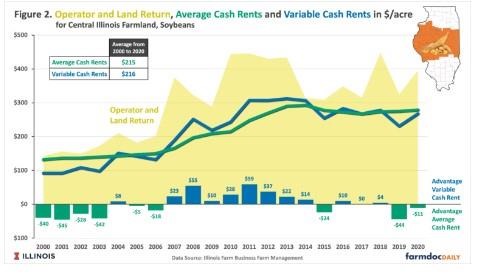

Cash rents using 32% of corn crop revenue were calculated for high-productivity farmland in central Illinois and compared to average cash rents in Figure 1. Several periods are notable. Variable cash rents were significantly above average cash rents in 2007 ($51 per acre), 2008 ($197), 2011 ($108), and 2013 ($32). The 2006-2012 period was associated with higher commodity prices due to growth in corn use in producing ethanol. As a result, the variable cash rent generated higher rents than the average cash rents during this period. The variable cash rent at 32% of corn crop revenue generated lower rents from 2014 through 2020. Overall, the variable cash rent is more reactive to commodity price and yields than fixed cash rents.

A similar analysis of variable cash rents is shown for soybeans in Figure 2. The variable cash rent generated higher rents than did a fixed cash rent from 2007 to 2014. Rents from the 42% variable agreement have been near or below cash rents from 2015 to 2018.

Other Revenues

Rents from the above variable cash rents do not include commodity title payments and crop insurance payments. The inclusion of these payments would complicate the variable cash rent calculations, thereby moving away from the concept of simplicity. If those payments wish to be shared, the use of a share rental arrangement seems appropriate.

Summary

The primary advantage of a variable cash rent is that the cash rent varies with gross revenue. It is difficult to anticipate price levels at this time of year when rental rates are being set. A variable cash rent reduces some of the difficulties in setting a fixed cash rent. Uncertainty about future prices appear more uncertain now than in previous years.

Rents in the next year will vary under a variable cash lease. As a result, the landowner will have more short-term risk under a variable cash lease as compared to fixed cash rents.

Other variable cash rental arrangements exist. The one above was designed to be straight-forward while accomplishing the objective of setting cash rent based on changing economic conditions.

Source : illinois.edu