The model is populated using multiple data sources.

The first point of contact is from the farm.

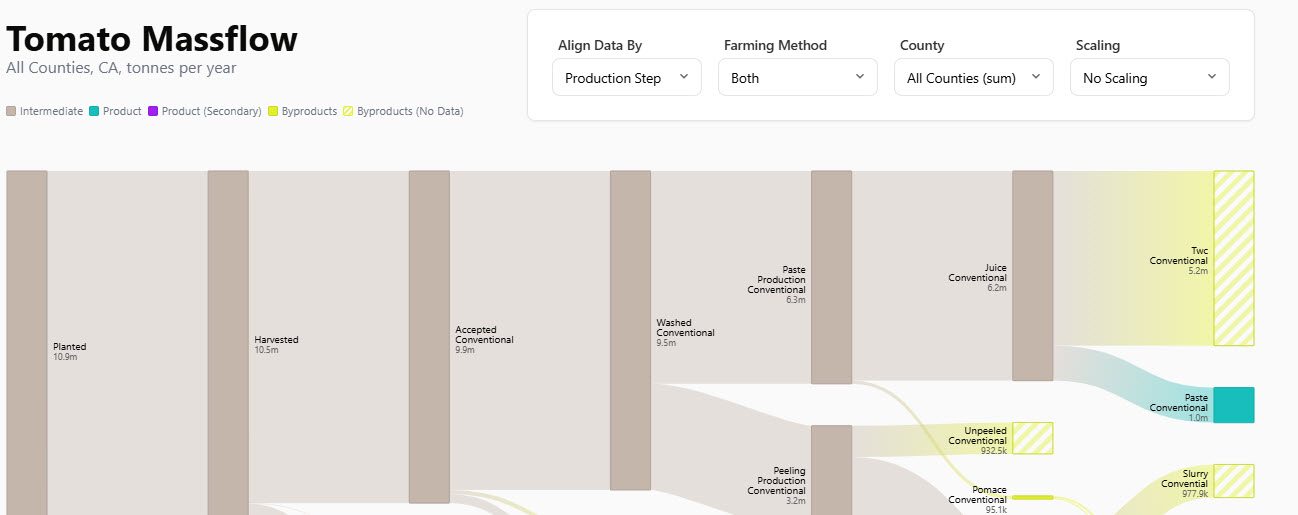

“We start in the field with USDA data to get a rough cut of what was planted and what was harvested,” he said. “Then we follow it through grading and processing, talking with industry partners about what happens to these materials. Part of that is available through industry reports.”

Tracking the crop from the farm to the processor is called the flow.

And within that there’s different flows – like tomatoes that make the grade for the grocery store versus the ones that don’t.

The online tool currently tracks byproducts of almonds, pistachios, pomegranate, and tomatoes. Wine grapes will be added soon, and work on olives, stone fruits, and other crops in California are planned for the future.

Finding new uses for byproducts is called upcycling.

In tomatoes, for example, the pomace (dried and crushed skins and seeds), are high in lycopene, an antioxidant the body doesn’t produce on its own.

And lycopene prices can range from $10 to $1,250 per kilogram, market reports say.

And in pistachios, there’s an abundance of leftover hull, which can be used to improve soil health.

Spang and his team created the database for all to use.

Academics like him can use it to understand what’s happening to ag material.

“Then there’s entrepreneurs in the upcycling community that are using these materials that have been overlooked to make new products,” Spang said. “It’s possible growers or processors might be looking for ideas of what to do with their material. They can reach out to the entrepreneurs and find ways to extract that value.”

While the Byproduct Database currently focuses on horticultural crops, the tool could branch out to include row crops like corn and soybeans, Spang said.

“We want this to be a tool that grows over time,” he said. “Once we build the model this could be used really for any crop in the world.”

Another challenge this tool helps tackle is food waste.

A 2024 report from the World Resources Institute shows about one third of all food produced isn’t eaten, and about 40 percent of food is lost or wasted along the value chain.

To put that number into context, global apple production in 2024/2025 was 83.98 million metric tons, USDA data shows.

This means almost 28 million metric tons of apples didn’t get eaten.

“Food waste is a big issue,” Spang said. “It represents carbon emissions, water use and land use that isn’t being put to productive use. With this tool hopefully today’s food waste can become tomorrow’s resources.”