By Edwin Akley

When planting soybeans in Kansas, it may be a good insurance policy to inoculate the seed. The Bradyrhizobium bacteria forms nodules on soybean roots, and these nodules fix nitrogen from the atmosphere and supply it to the plants. Neither soybeans nor Bradyrhizobium japonicum are native to the United States, so there will be no Bradyrhizobium japonicum in the soil unless it was introduced at some time in the past by inoculated soybean seed.

Why do we need to inoculate soybean?

- To enhance good nodulation

- To improve nitrogen (N) fixation

- To help ensure a stable yield

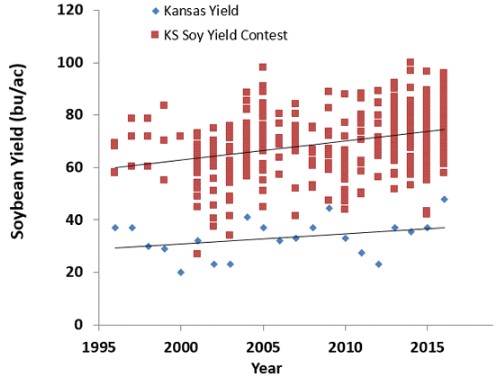

Soybeans are big users of nitrogen. For example, a soybean yield of 60 bushels per acre requires 300 lbs N per acre in the plants, removing about 3-4 lbs of N per bushel of seed (Figure 1). Most of the N required by a soybean plant is supplied via biological nitrogen fixation that takes place in nodules on the soybean roots. The nodules, when well established, can provide from 40-80 percent of the soybean plant’s N needs for the year. The actual contribution of biological N fixation to the N requirement of soybeans can be influenced dramatically by the amount of residual or mineralized N available in the soil profile or by stress conditions affecting the plant such as drought and heat, inhibiting N fixation due to the cost of maintaining the N fixation process.

Figure 1. Soybean yield and plant nitrogen uptake relationship from different regions in the US and Argentina. Data reviewed and synthesized by Dr. Ciampitti, K-State Research and Extension.

Yield responses to inoculation have been quite variable in Kansas and other surrounding states. But the cost of buying pre-inoculated seed, or inoculating the seed or soil yourself, is low and the potential yield loss from poor inoculation can be significant unless available soil N levels are high.

Figure 2. The soybeans in the part of the field at left in this photo had good nodulation. The area of the field on the right had poor nodulation and exhibited nitrogen deficiency symptoms.

Figure 3. Well-nodulated soybean plants (left) compared to plants without nodulation.

Soybeans that are poorly nodulated will have to take up most of the N they need from the soil, just like corn, sorghum, wheat, or any non-legume crop. Because N fertilizer is generally not applied for soybeans, a crop that is poorly nodulated will quickly use up the available N in the soil and become chlorotic (yellow) from N deficiency. For poorly nodulated soybeans, N deficiency is usually evident later in the growing season as the nutrient demand increases.

Why is the yield response to inoculation so variable?

There are several reasons for the variability in yield response to inoculation. For one thing, if soybeans have been grown on the field in previous years, there may be enough Bradyrhizobium bacteria in the soil to nodulate the soybeans adequately, in which case an inoculant may not benefit the crop. But if there is not enough Bradyrhizobium in the soil, the inoculant may increase yields by 2 bushels per acre or more on fields that have had soybeans in the recent past. On fields where soybeans have never been grown, the inoculant can often increase yields by 10 bushels per acre or more (Table 1).

Table 1. Effect of soybean inoculant on land with no prior history of soybeans

| | Kansas River Valley Experiment Field, Rossville | Southwest Research-Extension Center, Garden City |

| Treatment | Soybean yield (bu/acre) |

| None | 56.9 | 33.9 |

| Seedbox inoculant | 57.8 | 39.6 |

| Seed-applied inoculant | 66.4 | 43.5 |

| LSD (.05) | 9.8 | 3.6 |

Even on fields with no history of soybean production, inoculation may increase nodulation but still have no effect on yields – especially if the yield environment is low and soils have enough available N to supply the crop’s needs (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Soybean yield at East Central Experiment Field, 2016. Treatments include inoculation at normal, 2X, and 3X rates; and 300 lbs/acre of N. There were no significant yield differences. Data from K-State agronomists Ignacio Ciampitti, Eric Adee, Jim Kimball, and graduate student G.I. Carmona: http://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1233&context=kaesrr

Figure 5. Research by K-State agronomists Kim Larson, Kraig Roozeboom, and Chuck Rice. http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/16303

Yield response to inoculants can also depend on soil pH, environmental conditions, and other factors.

Soybeans should be inoculated in the following circumstances:

- Where the field has not been planted to soybeans for the past four years or more: Bradyrhizobium japonicum do not compete especially well with other soil microbes over time, and their numbers often gradually decline unless a host plant (soybeans) is grown every few years or new populations of the bacteria are introduced regularly from inoculated seed.

- Where the soil pH is less than 5.5 or greater than 8.75: Bradyrhizobium japonicum does not survive well in the soil under these pH extremes, and good soybean nodulation is unlikely unless the seed is inoculated. At more normal pH levels, from pH 5.5 to 7.5, the effect of inoculation will vary with the other conditions mentioned above. However, soybean yields will be reduced at pH levels below 6.0 regardless of inoculation (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Lower pH levels reduced soybean yields in this research by K-State agronomists Doug Shoup, Dan Sweeney, and Ignacio Ciampitti. In this research, inoculation had no significant effect on yields. This field has beans in the rotation every other year, so a response to inoculation isn’t necessarily expected.

- Where soil erosion has occurred since the last time soybeans were grown: If some of the topsoil has been lost, the remaining topsoil will need to be replenished with Bradyrhizobium japonicum from the seed inoculant.

- Where soil organic matter levels are less than 1 percent: Soils with low organic matter levels have less Bradyrhizobium japonicum and need to be replenished with new sources from the seed inoculant.

- Where there has been severe drought or flooding: Severe drought and flooding reduce Bradyrhizobium japonicum populations in the soil. Just a couple days of saturated soils, however, should not adversely affect Bradyrhizobium japonicum populations in the soil.

Based on previous information, inoculation is usually effective when:

- Soybean was never planted before or in the past 3 to 5 years

- Soil pH is below 6.0

- Soil has a high sand content

- Field has been flooded for more than a week, creating anaerobic conditions, when nodulation was supposed to become established

- Early-season stress conditions (e.g. heat) affects plant-bacteria establishment

Producers should be aware that inorganic soil N will reduce nodulation and N fixation by Bradyrhizobium japonicum bacteria. Where soil N levels are 40-60 lbs per acre or more, soybean plants may look fine, yet have reduced nodulation. At very high N levels, such as where the field was fertilized for corn but the producer decided to plant soybeans instead, there may be little or no nodulation. In most cases, up to 20 lbs N per acre can be applied as a starter fertilizer to help get the soybeans started without having any detrimental effect on nodulation during the growing season (unless the upper layer of soil is already rich in inorganic N at planting time).

Soybean inoculation is basically “cheap insurance” against a potential N deficiency problem. Even if soybeans have been planted in the field recently, it doesn’t cost much to inoculate the seed.